NORTH FORK AMERICAN RIVER COUNTRY: An Intrepid Exploration of New York Canyon: A Vast Speck of Paradise Deep in the Tahoe National Forest

It’s on all the maps. You’ll find references to it on web sites. The rangers know about it. It’s nearly in the Bay Area’s back yard. But few dare to venture the near trackless and ridiculously rugged terrain you’ll encounter.

.jpg)

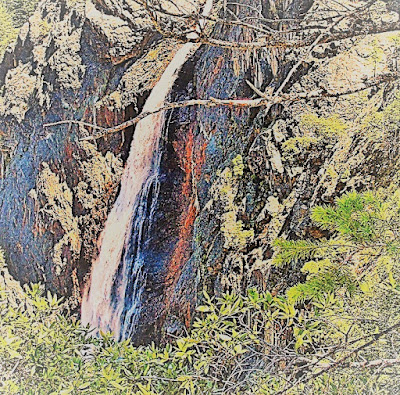

Those who do manage to stage an adventure hike to this secret and remote location are rewarded with stunning views of a magnificent 500+ feet waterfall that tumbles from an isolated high gorge formed by the West Fork New York Canyon Creek to indeterminable depths defying calculation other than HOLY COW!

.jpg)

Certainly, this place would be a national park if it were even halfway accessible. But it’s not even a State Park, or even a "park" on anyone’s radar screen: the place is nearly untraversable, virtually inaccessible.

Only Russell Towle or Ron Gould could get you through there safely.

It really amazes me that such a place exists so near to the hustle and bustle of the Bay Area.

.jpg)

It’s only about two hours away by car. All these years, here I’d been just zipping by the low foothill country beyond Auburn, where Gold Rush fever began, never so much as glancing out the window at the pretty but humdrum landscape south of Interstate 80 – of course, always on my way to bigger, better places in the High Country of the Sierra Nevada.

.jpg)

What I’d been missing just can’t be seen. You need to be told about it, guided there. You look out there and see some nice ridges, but nothing jaw-dropping, nothing to rally your inspirational senses to want to explore it.

.jpg)

Not when the John Muir calls, or the Desolation or the Eastern Sierra is waiting.

Such a pity.

.jpg)

Now that I know this area somewhat, I say, give me the glaciated lower reaches of this Sierra land any day!

.jpg)

Give me the raggedy 2000+ feet high cliffs, the sweet turquoise waters of the river on hot August days, this land of pleasure and paradise, of magic and mystery, and fascinating history.

.jpg)

Because what we’re talking about is extreme topographical relief for such lower elevations: soaring crags and towering ridges, one deep, steep motherhumper of a canyon that is, for all intents and purposes, hidden from the world.

.jpg)

A canyon half as deep as the Grand Canyon! A canyon one-fifth as deep as the Grand Canyon would rank as mighty impressive!

.jpg)

And so it was on June 14, a hot and sunny day, that Russell and I undertook an epic circumambulation of this wild territory, probably named by some wayward Empire State miners back in the forties, the 1840s that is.

.jpg)

Personally, I’m convinced that the route Russell and I took, from the Falls back up the ridge to the road, has never been done by a human in modern times, for this is the off-limits realm of mountain lion, the recondite kingdom of bear, the unfettered domain of highfliers.

.jpg)

Humans are fragile and puny out here; one slip, one mishap, and you could die in your shoes right there and only the circling vultures would be the wiser.

.jpg)

We began high above the snow line, on Canada Hill (where we would later emerge from our ridge scramble), at around 6600 feet. From there we walked to Sailor Flat jeep trail, the dreaded inroad to Oak Flat.

.jpg)

Here, we catch the trail down, down, down to the river. The Falls is just over the ridge from there, as the crow flies probably not even a mile. And yet it’s so tucked away in those rugged gullies, you would never suspect anything out of the ordinary, least of all a cascade to rival lower Yosemite’s famous plunger.

.jpg)

Just before Oak Flat, we ducked into the forest at a calculated point, and charted our cross-country course to the Falls. We had to keep a straight line or else . . . you’d end up lost and unable to scale the gigantic cliffs forming the eastern base and walls of the gorge.

.jpg)

At precisely the same spot as last year, when I first visited the Falls, Russell led us down a couple hundred feet below the sight line – to my chagrin and his mystified disappointment.

.jpg)

Finally, though, after much up and down and huffing and puffing, a few curses back and forth, he found the line, which turned out to be a fine little trail that provided sweeping and majestic views of 8,000-foot Snow Mountain.

.jpg)

Its entire western spur extends nearly two miles to the carved-out gouge that is Big Granite Creek and that canyon confluence where Mary and I have camped every birthday since 1999 when we first discovered it quite by chance in a swimming hole guidebook whose author Mary once worked with in a St. Louis bistro.

.jpg)

Snow Mountain just blows me away. Rising damn near one sheer mile from the river bed, it is a massive chunk of earth, a sprawling mountain at the lower end of the famed Royal Gorge. It’s doubtful anyone’s climbed it from this angle; Russell has approached it from the north and reached its topmost summits.

.jpg)

From where I stand, you don’t mess with Snow Mountain, only gawk at its incomprehensible bulk dominating the horizon.

We made excellent progress along the sight line, with Russell heading the way, loppers in action the entire time to clear brush and create more favorable trail conditions.

.jpg)

Russell is a tireless trail advocate, nature activist, defender of all things wild. He grew up in the South Bay, I think, and has been living in North Fork country, in Dutch Flat, for over thirty years. He knows North Fork country better than all the rangers in the TNF and BLM combined.

.jpg)

His extensive geologic, botanic and historical knowledge of the area, coupled with his boyish enthusiasm for high-adrenaline adventure hiking, has lent him a certain cachet among the canyon crazed cognoscenti.

.jpg)

In other words, if you get lost in North Fork country, better hope you’re with Russell Towle. I met Russell on the internet where he (once maintained) a fine web site and invited myself along on one of his expeditions.

.jpg)

It always struck me as odd that Russell carried in the loppers. Once, during a loquacious spurt along a particularly overgrown stretch, Russell (or was it me?) admonished:

"More lop, less lip."

.jpg)

That became our mantra. I’d see him snip down a small pine tree, or butcher a manzanita, and I’d cringe. But his reasoning, as usual, was unimpeachable. I just didn’t want to wield them, being along for the ride, so to speak.

After much up and down we came to a great open rocky area, which was really the top of the cliff forming the east wall of the gorge through which the Fall plunges so spectacularly.

.jpg)

It was a relief to emerge into the open, bright sunlight, see this primitive world in shining glory, Snow Mountain looming larger than ever now. Even though Russell mourned our late arrival, insisting it was ten times as spectacular a month ago, the Falls proved worthy of all the “trouble”.

.jpg)

But a month ago, the only way in was by ski. As it was, or turned out to be, I did not feel cheated. Given the huge snow pack and recent melt, the Falls was better than I remembered it from last year.

.jpg)

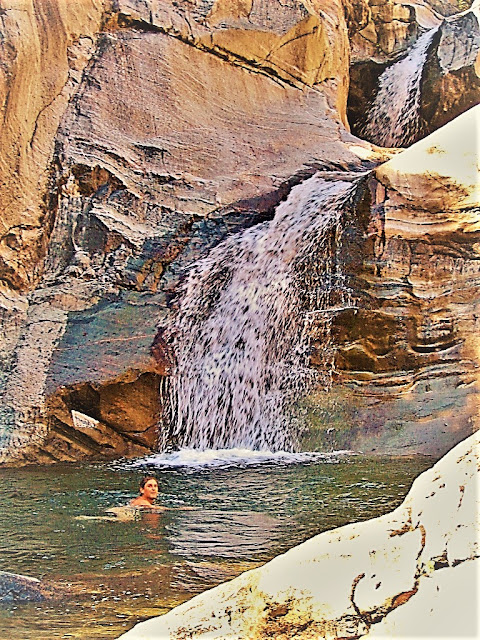

This rocky top was chock-full of wildflowers in lush bloom, growing out of every nook, cranny and crevice – brilliant pink penstemon, bouquets of blue dicks and scattered poppies, bunches of lupine, paintbrush and monkeyflower, dazzling varieties of moss, ferns and lichen. Butterflies and bees, hummingbirds and swallows, the roar of water all around – it was the East Fork New York Canyon Creek. There, near its swiftly flowing course, we took a break.

.jpg)

I got in, nearly froze my balls off. Nothing like a bracing baptism in ice-cold virginal waters to rejuvenate and inspire!

The next amazing thing along the way was the Chert Dome, a massive plug of rock rising up from below to a height of maybe a thousand feet. It stood there defiantly, off-limits to all but a few, cutting the divide between the two forks of New York Canyon’s creeks, the East and West Forks.

We descended 600 or 700 feet to its west fork base (the east fork base jutted down another several hundred feet to the gushing water headed to the North Fork American River). As we climbed the scalable walls of this improbable knoll, the grand views of the gorge and Falls started appearing. One breathtaking scene after another.

.jpg)

On a dizzying precipice, poised to capture rainbow spray, Russell looked down and detected bear scat – aah, what better place to unload than from this precarious perch, surely the Mother of all Thrones?

The bears, in fact, were with us and all around us, but hidden and unseen, generally averse to any encounter with stinky humans.

.jpg)

They were probably watching us, yawning. Russell, ever on the lookout for signs of intelligent life in the wild, pointed out scratches on fallen logs, broken branches, and the inimitable prints of their weighty paws pressing down in the same spots, over and over in soft mossy areas, to leave behind the trace of their eternal comings and goings.

.jpg)

On the climb out, up and over Chert Dome Ridge, we traversed a long stretch of bear trail – christened Ursine Trail after the creatures who made it.

The views from atop Chert Dome were stunning in all directions.

.jpg)

Looking north beyond Snow Mountain’s big western spur and Big Granite Creek’s canyon, beyond Cherry Point in the distance, lay the high Loch Leven Lakes, twelve or more very tough foot miles away, and right below that, Highway 80 roaring into Truckee and Reno with its river of mechanized traffic.

.jpg)

As the crow flies, no more than three or four miles away. But it might as well be light-years.

The day was passing, and we knew it was time to bid adieu to the sacred Falls and Chert Dome and big New York Canyon’s creeks.

.jpg)

Russell suggested we continue the loop by climbing the spur ridge back up to Foresthill Road at Canada Hill, maybe a 2000+ foot hike up and out. It’s one thing to that on a trail; another thing entirely to find your own way in uncharted territory. (As I said to Russell, “We may be ascending, but we’re not yet masters.”)

.jpg)

From the Chert Dome, which forms the base of the ridge, we began climbing, easy going at first, and triumphant at each crest. After an hour of slogging up and over apartment-size boulder outcrops, and through leg-wrecking manzanita brush, we crested about five times, and I was starting to flag. I never once doubted Russell’s route-finding abilities, however, and trusted his every directional sense.

Sure enough, 2.14 miles later, the final three-fifths of a mile over refreshing snowpack, we emerged on the road – a most welcome sight! – right near the car.

It was an exhilarating day of hiking, bushwhacking and exploring deep in the heart of a wilderness area not many get to appreciate.

I truly feel privileged to be witness to such a place and thank Russell for putting up with all my whining, moaning, and complaining about "being lost" and "dead tired".

.jpg)

Long live this incredible beautiful magnificent wonderful amazing wilderness in the heart of Russell's favorite place on Earth:

North Fork American River Canyon Country.

Honoring Russell Towle:

Check out more Gambolin' Man adventures in California's great American River canyons:

.jpg)

Grab a beer & settle in for some live (but shaky!) footage deep in the heart of NORTH FORK AMERICAN RIVER canyon country:

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)