GOLDEN GATE NATIONAL RECREATION AREA: Pedal Powerin' Across the Golden Gate Bridge from Berkeley to San Francisco to the Marin Headlands & Back

Conventional wisdom says that to live a quality, outdoor-oriented lifestyle amidst the Bay Area’s one hundred and one cities, owning a car is an absolute necessity; otherwise, how is it possible to get away from it all, to escape the metropolitan madness and get out and about and into the heart of nature?

How? Easily. With a bit of creative planning, an imaginative spirit, the right attitude, and plenty of time on your hands, all you need is a little help from public transportation – BART, bus and ferry – and a good set of wheels (only two required).

And you're ready to go, secure in the self-empowering knowledge that you can rely on your trusty bike to get you to the brink of almost anywhere in the Bay Area, on the purlieus of open spaces, to the edges of wild places.

Where a get-away experience is within reach, involving limitless fun, unbridled adventure, and rewarding physical exercise while taking in – as we do on this particular outing – incomparable scenic wonders and historic attractions rivaling anything on the planet for sheer exotic sensorial bombardment.

All by bike!

Nearly a year and a half ago, we decided to partake in the great eco-friendly experiment that not many are able or willing to join – giving up the slavish car-centric lifestyle and living a cleaner, greener, healthier existence, free of being addicted to oil to the extent possible in this modern age.

Now, unless you're a hardcore PlanetWalker like John Francis, you can't expect to ever completely sever the umbilical cord that yokes you to oil dependency. But the amazing John Francis did.

In 1971, on the heels of a calamitous oil spill – two tankers collided in the fog off the Golden Gate, releasing nearly one million gallons of toxic goo into the then-pristine bay – the young Marin County hippie / musician / drifter was jolted out of a complacent lifestyle and decided then and there, once and for all, to renounce cars altogether.

That was a decision many condemned with cries of surprise and whispers of disbelief, while others – rednecks driving down the road – mocked and physically threatened and verbally abused him.

An even more radical act would follow when he forsook all forms of petroleum-based transportation, refusing to board any motorized oil-dependent contraption – boats, buses, trains or airplanes – and so embarked on a twenty-two yearlong walking odyssey (talk about time on your hands!) across the United States.

During which time he also took on a seventeen yearlong vow of silence while – get this! – managing to earn a Master's degree in environmental studies AND his doctorate in land resources. Makes you wonder how he defended his "orals"! Read his fascinating account in his lovingly rendered and lyrical book PlanetWalker to find out.

Nowhere close to being PlanetWalkers, we nonetheless have reduced our reliance on cars / oil, and in this simple renunciation that many could make just as easily, we have dramatically minimized our carbon footprint – and we're healthier for it and the planet is a wee bit better off for it, too.

Thinking at first giving up our car would be a monumentally difficult commitment, imagine our surprise – and relief – to discover just the opposite occurred. From day one, practically, we never looked back.

Apart from the huge monthly savings of no premium, no insurance, no gas, no maintenance or repair costs or depreciation – hard dollars in the pocket at the end of the month – what can top being self-reliant on your own two legs and trusty two-wheeler to get around?

It is truly an empowering act of countervailing resistance, capitalistic disobedience, a flip of the middle finger to the conventions of the ordinary and capitulations to the expected. But what if we really need, really want a car?

In such instances – and heaven knows, I love the ease, comfort and convenience with which a car can get us places! – we have signed up for CityCarShare, or we rent a car for weekend camping getaways, or a friend has generously loaned us his vehicle on more than one occasion.

So, to the extent that we're able, being car-free means we bike nearly everywhere out of necessity for our daily errands and normal "around town" lifestyle – to get our groceries, to do laundry, to get to work, to get to our nearby parks in the Berkeley and Oakland Hills, and to visit friends.

And – it bears repeating – we haven't looked back.

But when, you want to know, will we end the experiment? When, you wonder, will we tire of the "inconvenience"? When, you figure, will we break down and buy a car when the novelty wears off and the pressures of conformism bear down ever harder?

As Melville's Bartleby the Scrivener was apt to say:

"I would prefer . . . not to."

And so it goes that I suggest to Gambolin' Gal:

“Let’s get off our lazy duffs and haul our bikes over to the city on this perfectly gorgeous day and bike across the Golden Gate!”

This is a singular escapade that everyone must experience at some point, and it sure seems like everyone in the world has decided to experience it all together at the same point today!

At first, she demurs, but I press her and describe what the fun and adventure, the novelty of it – and, oh, the horrors and hassles of it! – entails, and it doesn't take much more convincing than that, before she leaps up off the sofa and prepares for the impromptu outing.

Hey, why not, embrace the day! Seize it! With the morning already half wasted away, we hurriedly pack provisions, hop on our bikes and ride over to the North Berkeley BART Station, where we catch a thirty-minute train to the Embarcadero Station at San Francisco's waterfront.

(If the train compartment's not crowded, it's a breeze, but when it's packed with people, as it is on the return, dealing with your bike can be a minor bitch.)

Once spit out at the Waterfront, we're in one of the world's great cities, us and our bikes, and well, we feel like we can set off in any direction, go and end up anywhere.

A sensation of pure freedom courtesy of our Trek and Gary Fisher bikes.

The near twenty-mile round trip excursion bends the mind and slackens the jaw, for its wealth of contrasting weather patterns, variable urban and natural scenic attractions, and wildly different ambiences.

And for its fantastic scenery, dishing up one fabulous view after another, on the approach, from on high, looking back, from whatever your vantage point may be, of the iconic, world-famous, hugely admired and photographed Golden Gate Bridge connecting San Francisco to the rugged Marin Headlands.

And what a bridge it is – described in a 1937 poem by chief engineer Joseph P. Strauss:

“Resplendent in the western sun / The Bridge looms mountain high / Its titan piers grip ocean floor / Its great steel arms link shore with shore / Its towers pierce the sky.”

The Waterfront is electric with people strolling through aisles at an outdoor fair, gathered around a mercurial drummer performing a blazing hot routine in the plaza bangin' on a motley assemblage of pots and pans, and the boulevard ambience is hoppin’ with rollerbladers, skateboarders, joggers, bicyclists, Segue operators, and pedestrians all out enjoying the lovely day.

In a way, I'm amazed (aren't YOU?) at my pococurante attitude of just going along with the flowing logjam of humanity, accepting without a whimper the hubbub, and dealing so mellowly with the intermingling masses of people – for it's the absolute last place on earth you would expect to find Gambolin' Man (isn't it?) on a brilliant spring day, dodging hordes of tourists and playing chicken weaving in and out of insane traffic.

But it's all part and parcel of what makes this adventure the memorable experience it is; this urban four miles or so covers a good stretch of the Waterfront, from the Clock Tower to one pier after another to famous Pier 39 and Fisherman's Wharf, and various parks and fields, with outstanding views every which way you turn.

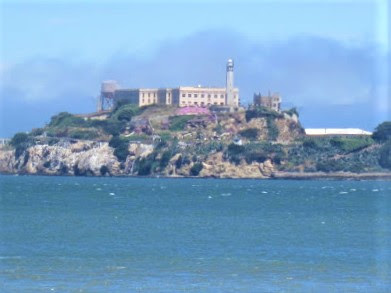

The Bay Bridge, Alcatraz Island, Angel Island, the red tiled roofs of Fort Mason, and gradually, lifting a tantalizing orange spire out of heavy fog, the Golden Gate Bridge coming into view by the time we roll onto Crissy Field, a former airfield named after Major Dana H. Crissy, who died in a plane crash in 1919.

Much of Crissy Field's pristine features – marshes, dunes and shoreline – have been restored to a 100-acre waterfront beloved and enjoyed as a sanctuary and playground by residents and tourists from around the world. (As well as critical wildlife habitat for many animals and plants that thrive in this urban oasis, this refuge of littoral nature.)

Much of this part of San Francisco is renowned for its inclusion in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, a multi-sectioned swathe of preserved federal lands encompassing nine different natural features and ecosystems – beaches, forests, intertidal and subtidal zones, oceans, prairies and grasslands, rivers and streams, sand dunes, scrublands, and wetlands, marshes and swamps.

All this amidst a heavily urbanized, highly populated, tri-county area, spread out over 75,500 acres in Marin, San Francisco and San Mateo counties, and laden with historic significance and ecologically sensitive zones.

The historic attractions include military installations, forts and hillside bunkers dating back to Spanish colonial, Civil War, World War II and Cold War eras – strategic locations perfectly situated for coastal fortifications on the lookout for enemies unseen, imagined and otherwise.

Much of the land has been preserved in its natural ecostate – the GGNRA and twelve adjacent protected areas are UNESCO-designated as part of the Golden Gate Biosphere Reserve.

Crissy Field, fronting a stunning view of world-famous landmarks, along with Muir Woods, where ancient groves of Redwoods have survived, Stinson Beach, Olema Valley, Sweeney Ridge, and many, many other places encompass sixty miles of bay and shoreline and harbor nearly 1300 plant and animal species, at least 36 of which are considered threatened or endangered.

With the prospects of upwards of thirteen million visitors yearly, the concern is that sensitive species will be impacted, habitat loss accelerated, and biodiversity diminished. But what are you gonna do other than "manage" it?

And hope for the best. And be prepared for the worst.

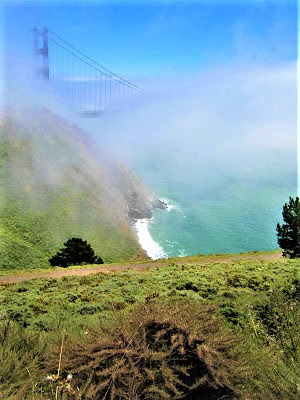

Arriving at the entrance to the bridge crossing is a bit of a let-down, as the wind's blowing fiercely, and everything is drenched in a thick pea soup of San Francisco's famous fog – yet another marked contrast from the brightly lit day we leave behind along the Waterfront.

Unable to see a thing except our immediate surroundings, we're mildly disappointed, but I also suspect it will be just the opposite on the way back, later in the day. Many cyclists are making the crossing, a majority of them international tourists on rented bikes (nice business I should be in!).

Others are casual riders like ourselves, not in any hurry, and of course, there's always the handful of hard-core, get outta my way, I'm comin' through types too, too too inconsiderate to slow down, breathing down your neck or zooming dangerously past a tight lane of single-filers just out enjoying themselves in a leisurely fashion.

Given the obscured scenery, I guess there is no real reason to linger, but we manage to dawdle here and there, peeking over the bridge railing to a dizzying view of a scimitar shaped, barely seen rocky beach or a patch of abstract whitish blue water lapping in an aqueous bed below us.

With a glimpse here or there of wispy fog rising to reveal green hillsides in splendid isolation rising high above the tide, and crazy discorporate parts of the bridge – curvaceous spans and towering spires – appearing and vanishing at the whim of the dancing fog.

Once off the 1.7-mile span, with its maddening river of mechanized vehicles roaring by in a ceaseless rush of traffic, we're relieved and happy to find ourselves pedaling in sunnier climes up the steep and winding main Headlands thoroughfare, Conzelman Road.

Up, up and away, into the fogless altitude, we ride, pulling off at all the designated spots to take in the world-famous views of the Golden Gate Bridge, now standing out in full polychrome relief against a stark blue sky, with its twin 746 ft. tall spires jutting skyward in their art deco glory.

And bedazzled by that shimmering vision of urbanity – Baghdad by the Bay – and beyond, beyond, to the East Bay Hills and the faint triangular eminence of Mount Diablo itself probably thirty-five miles distant on the hazy horizon.

Continuing our ascent, we’re suddenly stopped in our tracks about a mile up by a serious road barrier with a NO BIKES sign posted. Looks like they're repairing the road higher up toward Point Bonita Lighthouse, but no matter to us, since our plan all along has been to ditch the road for the spur shortcut, Coastal Trail.

This is a fab stretch of legal dirt single-track that suddenly transports us off the asphalt world of cars, cars and more cars, and into an entirely different realm.

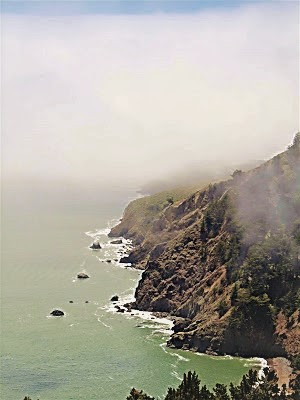

And yet another contrasting world of hills, hills and more hills, partly enshrouded in a veil of lifting fog to create a mysterious ambience as such you might expect to encounter in Scotland's Southern Uplands region (at least how I imagine it might appear).

Looking west, it's clear enough to catch a glimpse of a gleaming patch of tantalizing blue ocean stretching to the infinite horizon – Rodeo Beach in our shimmering dreams.

The sense of liberation from all earthly cares and concerns is intoxicating. Freedom shoots through our veins as we whiz down the rocky trail in this suddenly pristine, wild setting; long gone, light years behind us, is any and all traces of civilization.

Now hemmed in by the unbounded hill country of the glorious Marin Headlands, the sudden and immediate contrast couldn't be greater. One minute city, steel and concrete, the next nature, big open sky, plants and earth.

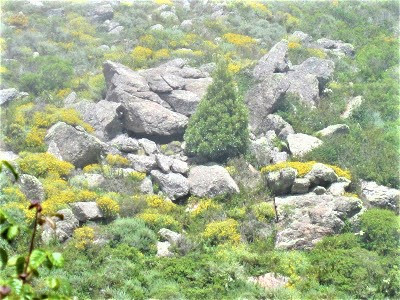

California poppies, Indian paintbrush, monkeyflower, sweet purple vetch, and silver-leaf lupine abound, the latter an endemic species critical for the larva of the endangered and also endemic Mission Blue Butterfly.

Many other "lesser" unidentified wildflowers are in bloom, a smattering of color creating a painterly vision of paradise along the trail and across the hillsides. We stop to admire a small bluffside, decorated with succulents popping with tiny yellow blooms, and happen to look up and see a big doe standing motionless staring down at us during a pause in her grazing routine.

Nonchalantly, she continues chewing and chomping on her little cud, then saunters behind some boulders.

The route continues another mile or so down to the flats of Rodeo Valley, a winding descent where it's easy to pick up speed at a dangerous clip.

The trail conditions are slippery and rocky, with ruts and holes, so we moderate the thrill of an unbridled whooshing reckless descent – the thrill of the “downhill bomb” in mountain biker parlance. But what's the everlasting hurry, for goodness sakes? Every step – or revolution – of the way presents an eternal moment to take in the sights, to observe our intimate and long-view surroundings.

We’re down sooner than we want to be, and from there it’s an easy haul. We come to a big meadow off Bunker Road and the first thing we see are two stiffly frozen, elegant statuesque blue herons on the hunt, probably for snakes. Unconcerned by our presence, we drop our bikes for a few minutes of viewing.

They begin to unwind in stealthy motions, taking on awkward gestures, craning their long, curvy necks forward in exaggerated fashion, lifting one spindly leg high and then the other, stepping deliberately in a slow stalking trance. I could watch them all day in their patient diligent search for a tasty appetizer.

Only once have I seen a heron snatch a snake and fly away with the dangling prize. This side of the Marin Headlands is where the forts and military installations and scientific establishments are – historic Forts Cronkhite and Barry, the eerily abandoned Nike Missile Site, the Marine Mammal Center, Headlands Center for the Arts, and the Marin Headlands Visitor Center.

The other side – approaches from Tennessee Valley – is pretty much all open space, miles and miles of interconnecting trails for endless hiking and biking and horseback riding, leading to high ridges with stunning pay-off views of the ocean and Mount Tamalpais, and secluded immersions in back hollows where coyotes howl and bobcats prowl, where hawks and harriers soar, and, if lucky, where you might hear a mountain lion roar.

We end our ride – actually, it's the halfway point – at Rodeo Beach, a very pretty, curvaceous stretch of brown sandy shoreline fronting a cobalt blue, roiling ocean whipped up by strong winds and crashing white-tipped waves popular with wet suited surfers.

We sit on a bluff with legs dangling over the edge, enjoying a well-earned lunch and watching the dudes ride the waves – mostly just enjoying the sensation of being where we are, right here, at the very edge of the West Coast, staring out into the Pacific void – and relishing in the satisfaction of having gotten here by our own means, of our own volition and human-generated pedal power.

We could linger forever in the magical light of the late afternoon, but it's time to gear up for the long ride back.

As we're passing by Rodeo Lagoon, Gambolin' Gal lets out a gasp of excitement when she spots a skulking young female coyote slinking around a picnic table (sadly scavenging for some scrap of victual to whet her corrupt appetite).

I move in, probably too close for comfort, for a more intimate look and photo op, and she seems very unconcerned, to the point of nonchalance, about my presence, so obviously, the little "kai-yote" has been around this block before.

Snapping away (my camera, not her gnashing teeth), she delicately lifts herself up on the table to scoop up in her jaws a discarded half of an Oreo cookie. Not good. But she thinks it is, judging from her lip-smacking approval.

She's really a beautiful creature, sleek if a bit gaunt, with piercing eyes that radiate an intelligent and sensitive nature. This is probably the closest I've ever been to a wild animal. (The park service, of course, would have a conniption fit over it, but I have done no harm and the animal does not seem bothered or testy.)

No sooner does she figure she's scavenged the lot of potential bounty around and off the picnic table, than off she scampers, across the road, up into a nearby field, and out of sight to, hopefully, happier hunting grounds.

The climb back up the trail isn't as bad (hard) as we suspected, and in no time, we summit the crest of the ridge and are back on Conzelman Road.

The fog over the bay and bridge has completely dissipated giving way to a blinding cerulean brightness, revealing from our high vantage point the full panoramic spectrum of the prettiest and largest bay in the world. (Some, those from Rio and Hong Kong harbor, would protest.)

Stellar views: From nearby Bird Island Overlook and Point Bonita Lighthouse, across the expanse of open ocean to Land's End, China Beach, Baker Beach, the Presidio, the Shining City, and, of course, exposed now in all its naked glory, the great span and towers and cables of the Golden Gate Bridge.

Truly breathtaking stuff – which explains the logjam of cars inching slowing up and down the road, looking to pull off at Hawk's Hill, Spencer's Bunker, or some other spot to get out and soak up the views.

By now we're really tired and butt sore from so much seat time, and the day is getting on – it'll be 7 pm before we make it back to our doorstep in Berkeley – so we opt against our original plan of taking the Sausalito Ferry to the SF pier, and instead retrace our route by cycling back across the bridge.

Good decision: we're treated to those prevalent views denied us on the approach. For some morbid reason, I stop to inspect the signage and emergency phone for would-be suicide jumpers to call for last-second help.

This is the dark side of the beautiful bridge. I peer over the edge of the four foot high railing, my eyes falling 250 ft. in a dizzying plunge of speculative fright, trying to imagine the pain and horror over 1300 individuals have experienced who have made the terrifying four second long, seventy-five miles per hour jump.

"Bones shatter, ribs are snapped like they were twigs, internal organs are ruptured, blood gushes out of bodily orifices, and the body keeps going down, deeper and deeper, into the hellish water. For those still alive, the plunge to the frigid water has decimated their body, but now they are so deep underwater that they drown."

Notwithstanding such a horrific, certain fate, about thirty people have survived. I freeze in my tracks for several moments of spacey contemplation, my gaze oddly rapt at the blanket of awaiting sea below, a pacific calm that greets jumpers' bodies like "a truck smashing into a brick wall."

It’s hard to imagine, but this beautiful setting is the most popular place in the world to self-destruct – averaging one every two weeks. On that grim note, we ride on, and I send out a last-second thought and prayer on the wind for the poor depressed souls who come to this spot for a very different reason from most of us.

Soon, we’re back at the Embarcadero BART station, no longer charmed and enthralled by all the urban activity and frenetic comings and goings and doings.

Reflecting on the day's expansive and diverse adventure, it will be difficult to ever again feel "trapped" or "bored" by the same old routines or passing laments of "being stuck" without a car.

For in such moments, I will recall Arthur Conan Doyle's words to the wise:

"When the spirits are low, when the day appears dark, when work becomes monotonous, when hope hardly seems worth having, just mount a bicycle and go out for a spin down the road, without thought on anything but the ride you are taking."

AMEN!

.jpg)

Stress melts away, worries and cares are vanquished, problems dissolve, and the batteries of hope and optimism are recharged, and the shrinking spirit is emboldened to face the coldhearted and brutal world with courage and fortitude another day counting.

Read more Gambolin' Man write-ups about incredible, fabulous, amazing Marin County:

Read more posts from Gambolin' Man on Marin County's incomparable and magnificent Point Reyes National Seashore:

|

Take a moment to enjoy some videos taken in various stunningly beautiful Marin County locales @  |