ROYAL GORGE: The First Annual Russell Towle Memorial Backpacking Trip into His Favorite Wilderness (North Fork American River Paradise)

.JPG)

August 7: EVERY DAY is a good day in the MOTHER OF ALL CANYONS!

.jpg)

The kind of pristine day he would have cherished, delighted, and reveled in – freedom from all earthly cares, respite from societal and family concerns, nowhere in particular to go, nothing pressing to do.

.jpg)

Oh, except for the promise of great adventure in a breathtakingly beautiful canyon so near and dear to his rugged heart.

.jpg)

I sense his palpable presence all around in the spirit form of his favorite animal totems – ground squirrels busily scurrying about, rainbow trout darting swiftly in clear pools, flirtatious chirpings of birds, and the fluttering butterflies.

.jpg)

There is scat evidence of bears on the prowl – but so far no “interviews”, as John Muir famously wrote of his encounters with Ursus americanus, the black bear, or Ursus cinnamomum, the reddish cousin.

.jpg)

Both so at home whether foraging in the lush meadows or cliffy recesses, wherever the insatiable search for food takes her.

Happily, three of his favorite birds – Water Ouzel, Osprey and Canyon Wren – make appearances.

.jpg)

I fancy such visitations are his way of saying "howdy" from the great beyond. But where are you, Ms. Rattlesnake?

.jpg)

Like Muir, who called them "the other big irrational dread of over-civilized people," Russell loved the venomous species of Crotalus and fondly referred to these environs as the "Rattlesnake Capital of the Universe".

.jpg)

Often, coming upon them sunning lazily on a rock shelf, he'd stop to talk to them, Muir-like, just to let them know he was a cool, two-legged interloper without a six-shooter who meant no harm. About his own rattlesnake interview, he once demurred: "Take it easy, big fellow, I'll stay well clear."

.jpg)

Plainly, he was fearless, perhaps even a bit senselessly naive, in welcoming their presence, for he wrote, in half-jest, about stepping on them: ". . . they soften the foot, somewhat, bless their little hearts."

.jpg)

We spot a great osprey flying overhead one afternoon and hear the lovely siren song of canyon wren serenading us bright and early one morning, and we watch the bobbing ouzels flirt and skirt along riffles, but the trails and rocky banks have pretty much been clear of rattlesnakes for the entire trip.

.jpg)

Russell would be wondering about this, trying to figure out their behavioral pattern; maybe the rain and coolness is keeping them hidden away in their dens. But then, on the return from an exploratory foray downstream, I “sense” the presence of one and mention it to Nate. (Maybe I was just bullshitting, but I like to think my animal medicine antennae are honed.)

.jpg)

Sure enough, within minutes, my premonition comes true. Along a cobblestone stretch of river, I stop dead in my tracks, momentarily startled by the unmistakable buzz alerting me to a potentially dangerous “big fellow”.

.jpg)

This one's a real beauty, who, like all good rattlesnakes, really wants nothing whatsoever to do with a two-legged, however peaceful the intentions, so she quickly slithers into a small rocky crevasse. Russell might have said, "Hey, little guy, take care, nice knowin' ya!"

.jpg)

I actually say to the shapeshifter, “Hey, Russell, is that you? Come out from under there and say hi!”

.jpg)

August 7th: EVERY DAY is a great day in the ever-changing, echoing, echoing, all-reflecting CANYON OF CANYONS!

.jpg)

The day of our memorial hike into the Royal Gorge in remembrance of Russell Towle, who tragically died one year ago in a freak auto accident near Sacramento. Few were the likes of him. His death left a giant gap in hundreds of people's lives.

.jpg)

Giant Gap, incidentally, was one of his favorite places in the great canyon located pretty much out his back door and down the long, winding trail to the river.

.jpg)

His shoes of large and legendary living are too big to fill, and the world is all the more impoverished for his passing. For those not familiar with this modern-day John Muir, Russell was an avid hiker, skier, climber, and explorer extraordinaire.

.jpg)

He was the local keeper of the embers of near-forgotten history. He was a tireless environmental activist, trail advocate and trailblazer, carrying his trusty loppers to open up trails wherever he went.

.jpg)

Once he quipped during an overly garrulous Gambolin' Man spiel, “Tom, how about less lip and more lop!”

.jpg)

He was a longtime resident of Dutch Flat, loving father of two beautiful children, Greg and Janet, faithful husband of his beloved Gay, brother and son of family members, and dear friend of countless admirers.

.jpg)

The Tahoe National Forest – and the North Fork American River canyonlands in particular – was Russell’s back yard and playground, his personal Range of Light and Paradise Found.

.jpg)

I was fortunate to have been counted among his many friends (for a short six years) and consider myself doubly lucky to have shared intimate moments with him on sweaty, scratchy, poison oak infested outings of unbridled boyish adventure.

.jpg)

Each a hastily, deliciously planned spontaneous expedition into near-uncharted territory in difficult to reach places in search of out-of-the-way waterfalls – Russell obsessed over them and thrilled to the core on finding them – historic mining sites, dilapidated cabins, and indistinguishable old trails.

.jpg)

I once described Russell as being:

.jpg)

“ . . . to local Western Sierra Nevada foothills geology, history, botany and literary musings what Thoreau was to Walden Pond, Twain to the Mississippi, Muir to Yosemite, and Leopold to Sand County.”

.jpg)

With the passing of time, this characterization resonates deeper, and his legacy surely grows stronger.

.jpg)

Joseph Le Conte, an early professor of geology at UC Berkeley, once described John Muir as:

.jpg)

“ . . . a gentleman of rare intelligence, of much knowledge of science."

.jpg)

He goes on to note:

.jpg)

“ . . . he gazes and gazes, and cannot get his fill. He is a most passionate lover of nature. Plants and flowers and forests, and sky and clouds and mountains seem actually to haunt his imagination. He seems to revel in the freedom of this life. I think he would pine away in a city or in conventional life of any kind."

.jpg)

Those who know him will chuckle and nod, for Le Conte's description of Muir holds true for our very own eclectic, ever-searching, ever-questioning, ever-wondering Russell Towle.

.jpg)

And so our backpacking trip is intended to honor and celebrate the life of an anachronistic, simple, and yet complex, man of many dimensions and layers – unheralded (as of yet!) doyen of nature literature; "amateur" (i.e., lover!) mathematical and computer modeling genius; weighty scholar and insightful historian (kudos due!).

.jpg)

Yes, many an esteemed professor sought Russell out for his detailed knowledge and theories of North Fork geology; romantic-cum-scientist (he so badly wanted to believe in the reality of UFOs, fairies, the supernatural); cosmo-philosopher; talented musician; passionate connoisseur of classical literature; a rare polymath and true autodidact who took to heart Mark Twain's dictum to never let schooling interfere with his education.

.jpg)

As his family wrote on his memorial website:

.jpg)

“Russ was self-taught; formal education processes were far too slow for his quick, deep, wide mind.”

.jpg)

Russell's favorite wilderness paradise lies hidden in the depths of a glacial-carved canyon somewhere, as the crow flies, not three or four miles from the motorized river called Interstate 80, deep down where a section of the North Fork American River flows that only the determined and fortunate (and possibly demented) get to experience.

.jpg)

The magical river begins in the high basin country west of Lake Tahoe, in the alpine headlands of the Granite Chief Wilderness. It crosses old Soda Springs Road on a forest service bridge around 6600 ft. and looks very much like an ordinary country creek.

.jpg)

That is, until it begins to lose elevation in a series of wild, plunging descents over 2000 ft. and several miles through narrow gorges and scoured granite boulders in the famously named Royal Gorge. Most are familiar with the Royal Gorge as a premier downhill and cross-country skiing destination at Donner Summit.

.jpg)

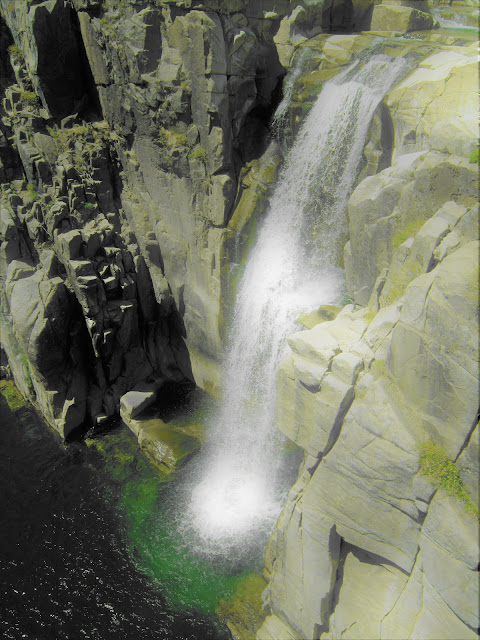

Legendary among a handful of kiss-your-ass-goodbye kayakers who risk their lives to navigate perilous stretches of the river at high flow, the North Fork in the Royal Gorge carves chutes and channels over "spiritually white" (thank you, John Muir) granite bedrock.

.jpg)

It magically forms bedazzling emerald green pools, and – were the water not so cold! – sculpts out kingly, luxurious soaking tubs; and throughout its churning course, the river presents some serious head-banging and knee-knocking challenges getting through, up and around impressive series of waterfalls and cascades in impossibly rugged and beautiful settings.

.jpg)

Perfect Russell Towle (and bear and rattlesnake) country.

Everything about the North Fork American River wilderness seems impossibly rugged and challenging. It is not an easy place to get to and venturing into this wild landscape is not an act to be undertaken lightly or without some back country route finding and wilderness survival skills.

.jpg)

You could injure yourself and die down there and no one might ever discover you, except perhaps a hungry mountain lion or scavenging bear! Most trailheads leading down from ridges on either side of the canyon require a 4-wheel drive high clearance vehicle.

.jpg)

And then – brace yourself! – the trails abruptly descend, sharply and steeply, over a couple of brutal short miles, making the way down a knee-buckling trial and ankle-busting tribulation that severely tests your mettle, your physical conditioning, and your state of mind for getting into such ridiculously difficult hiking predicaments.

.jpg)

You’ve really, really – make that REALLY! – got to want to be there . . . there being at the bottom of a veritable chasm in the earth more than half as deep as the Grand Canyon in some places.

.jpg)

At its highest to lowest point – from the top of Snow Mountain, a massive sentinel standing guard at 8014 ft. and dominating the lower portion of the Gorge, to the river bottom – it is an astounding 4000 or more feet deep! (Russell alternately cites 4000 ft. to 4500 ft.!)

.jpg)

Throughout much of its length, the canyon is easily 2000 ft. to 2500 ft. deep, and 3000 ft. of elevation is not uncommon in some parts of the Gorge area. Beginning around 6600 ft., Palisade Trail switchbacks over three miles and loses about 2400 ft. in hard to reclaim elevation.

.jpg)

We'll certainly feel it on the slog up and out. Actually, it is one of the "easier" access points down into the canyon compared to Big Granite, Sailor Flat, Beacroft or Mumford Bar trails.

.jpg)

Palisade Trail can be accessed from either ridge, and we choose to enter it from old Soda Springs Road on the saddle of the ridge between Latimer and Wabena Points – for an incredible "near view" of the Sierra Nevada.

.jpg)

Here is where the early twentieth century watercolor painter Lorenzo Latimer used to set up his easel to paint the scenic landscapes overlooking the wild upper basin of the North Fork – glorious visions of Snow Mountain, Devil’s Peak, Tinker’s Knob, Lyon and Anderson Peaks, Castle Peaks, and beyond, a visually sumptuous feast of granite alpine wonderland.

.jpg)

My friend Ron Gould, an expert on North Fork trails and history, hiking partner and friend of Russell’s, and author of the indispensable North Fork Trails Guide, is the de facto expedition leader, with Gay Wiseman our honorary spiritual guide.

.jpg)

Knowing only Ron can lead us in and out, I contact him about a memorial hike, and he subsequently contacts Gay about spending a couple of nights down in Russell's favorite part of the canyon, to commune with his spirit amid what he once described as:

.jpg)

“ . . . the magic and mystery in this wildest of all canyons in the Northern Sierra, with its romantic cliffs, its many waterfalls, and the roaring, sparkling river at its heart.”

.jpg)

Before we know it, a gaggle of friends are pining to tag along on the memorial outing – Greg Troll and his teenage daughter, Mirabai; Tom Peterson; and young Nate. Ron’s hounddog, Otis, a frisky loveable lunk of a Weimaraner, comes along for the ride, too. And, in a very literal way, so does Russell himself!

.jpg)

The original plan to reprise a canyon adventure undertaken on August 13, 2002, with Russell and Catherine “CanyonSpirit” O’Riley gets derailed. (Catherine, unfortunately, is unable to accompany us due to a rotator cuff injury sustained on a recent hike.)

.jpg)

That was our first meeting and I thought Russell was absolutely crazy, and just a hair ambitious, to be taking us down and back up in a single dragon’s breath hot day through the trackless Wabena Creek drainage wilderness.

.jpg)

I believe, too, he heaved a sigh of relief on seeing me:

.jpg)

"I had never met Tom in person, and saw that he was a tall, rugged fellow, with every indication that he was ready and able to take on a fairly drastic hike."

.jpg)

Well, "fairly drastic" is an understatement! As things turn out, the derailed plan works out for the better.

.jpg)

On the eve of the departure, Ron gets a call from Gay saying that Mirabai, in her rush to pack at the last minute, has forgotten her hiking boots. It’s a serendipitous little blunder, and I thank her immensely.

.jpg)

In truth, my bad ankle’s in no condition for the exposed Wabena descent, with its overgrown, indistinct trail, and talus-strewn sharp rocky slopes; and, more appealing, in all. my North Forkian romps, I’ve never descended to the North Fork via Palisade Trail.

.jpg)

I've never explored the Royal Gorge above Wabena Falls, and, most lamely of all, have never seen the fabulous Native American petroglyphs at Wabena Point, high above the river overlooking Snow Mountain and the thin ribbon of the North Fork.

.jpg)

So great is my anticipation of seeing them and experiencing a new dimension of the wilderness area, that I am actually quite happy we aren’t going down via treacherous Wabena. So, thank you, Mirabai, for forgetting your hiking boots! (But sorry about your thrashed feet and toes from hiking in Chacas!)

.jpg)

The revised plan calls for us to meet near Wabena Point at the trailhead. Ron, Otis and I arrive an hour earlier than the others, getting an early jump on the day and finding ourselves negotiating the rough and tumble, unpaved Soda Springs Road by 9 am.

.jpg)

The day is fresh and sweet-smelling from the previous evening's downpour. It looks like it might rain some more, but too late to worry about not having packed a tent, rain gear or even a tarp.

.jpg)

It’s my first time traversing the old famous road which once served miners and stagecoaches, and today is the main entry point into the high back country of the upper basin.

.jpg)

This is where the notoriously covetous North Fork Association, a group of wealthy old-money families, has established an off-limits, stay-the-hell out private resort called The Cedars.

.jpg)

Russell once “illegally” trespassed on an easement, an old Indian trail, called Heath Springs Trail, which the Cedars folk think is their own private trail; well, Russell wasn't about to be intimidated, but halfway down he was threatened with a citizen’s arrest by an over-zealous patrol guard. (So much for our right of access to public lands through easements!)

.jpg)

We pass uneventfully through their holdings, marked by sign after sign tacked to incense cedar trees warning of no trespassing, and finally we cross the North Fork bridge and enter the forest service's “managed timber lands”.

.jpg)

Russell’s bane, his cry and fury! Back in ‘06 in Big Granite Creek’s upper basin, during the course of our search for unnamed and untamed waterfalls, zigzagging through a patchwork quilt of private and public lands, we came upon a parcel that had been savagely logged, with horrendous razed destruction in every direction.

.jpg)

And for a full fifteen minutes Russell stood there, agape, angry and bewildered, railing away to me, to the shorn and blistered emptiness all around, arms held high and shaking mightily at some unseen, unlistening God, besmirching the evils of the chainsaw and lambasting the immorality, sheer stupidity and banal cupidity of logging virgin forests with 600-year-old, 10 ft. diameter trees!

.jpg)

.jpg)

After relieving himself, he takes off in a sniffing frenzy after some phantom gopher. We do the same (except the part about taking off after a phantom gopher), and make our way over to Wabena Point, a hundred yards away, to an elevated tor overlooking a dizzying panorama of the Royal Gorge.

.jpg)

Snow Mountain, the craggy Wabena Creek drainage, and the prominent peaks and rifts of Wildcat, Sailor and New York Canyons; the gleaming river lies nearly 3000 ft below us in the bluish distance.

.jpg)

Beyond, the humongous western spur shoulder of Snow Mountain cannot be seen, but far below, at Snow Mountain's broad south-facing base, the silvery blue thread of river abruptly disappears underground, forced to its subterranean egress by a massive payload of boxcar sized talus debris shed from the enormous slope during some bygone cataclysm.

.jpg)

For a full half-mile or more, the great river simply disappears leaving a riparian fossil bed as evidence of its soon to be resurrected grandeur a ways downstream from the jagged wreckage, impressive and awesome even viewed from so far away. Russell described this big talus area as:

.jpg)

" . . . a remarkable geological curiosity. It covers an area of somewhat more than a quarter-mile square, and is made of large angular boulders, dark with the lichen of ages. The slide appears to have formed in one cataclysmic event, perhaps several thousand years ago, originating on the side of Snow Mountain, and sweeping across the North Fork and *up* the south canyon wall, to a point about 400' above the river. In this part of the canyon – the lower, western part of the Royal Gorge – there are even larger talus slides, draping the sides of Snow Mountain, gigantic cones a thousand feet high, all Holocene in age, that is, more recent than the last glaciation, which ended about 12,000 years ago."

.jpg)

The elevated perch serves as a spiritual look out spot for modern scenery gazers and mystical contemplators. For those who came to this rugged, trackless wilderness, thousands of years ago, to pray, to conduct their ceremonies and rites of passage, to witness glorious sights, and to seek answers to the mysteries of existence, it was a highly sacred setting.

.jpg)

Here, overlooking the world, at the very center of their creation myths, artists and shamans – we really don’t know who – pecked their symbolic cosmologies into glacially-polished bedrock outcrops with primitive tools.

.jpg)

On a 10 ft. long, 3 ft. wide rock panel, lying on the ground slightly inclined, the prehistoric "Martis Complex" people inscribed petroglyphs sometime in the dim past of the Middle Archaic Period, perhaps as long ago as 1500 B.C.

In archaeological parlance, the petroglyphs are Style 7 High Sierra abstract-representational – largely indecipherable, intuitive-knowing sun bursts, bear paw prints, river-like Kanji characters, and squiggly connecting lines representing – who really knows?

.jpg)

The precise location of most of the 133 Northern Sierra Nevada fragile rock art sites are carefully guarded owing to defacement by careless and stupid people who treat these rare archaeological artifacts with little regard, suffering damage from foot traffic, vandalism, graffiti, spray paint, chalking, campfires, and outright theft of rock sections containing petroglyphs.

.jpg)

Russell loved this place, thought of it as a spiritual counterbalance to the off-kilter, Koyaanisqatsi world down below. I had always pestered Russell to bring me here, and he’d always say:

.jpg)

“Oh, one of these days, Tom, one of these days.”

.jpg)

And now, one of these days has come, and here we are, in spirit, with you, Russell. In a June 5, 2006 post, he mused lyrically and lengthily:

.jpg)

“We were chatting away down there by the big waterfalls, and Tom would mention this or that exciting place he had hiked in the mountains of California, and I remarked, ‘Tom, you know California better than I do! But, Tom, my good man, have you ever been to Wabena Point? No? Then you do not yet know the North Fork American.’ [He got that right!]

It has to do with the petroglyphs. Rock art, thousands of years old. A couple dozen sites are scattered around the upper North Fork. All are sacred ground. If a people lives here for thousands of years, they will know the lay of the land in a way we cannot imagine.

The lay of the land? I mean, the song of the land. And certain crescendos and passions are met, within that song of songs. That is where the petroglyphs are. Often they are in places which make perfect sense, some patch of Paradise like the Old Soda Springs, in the upper North Fork, where a giant whaleback of granite is incised with hundreds of designs, right beside waterfalls and mineral springs and pools and meadows, and all surrounded by snow peaks.

In ancient Greece, such springs would often become the sites of temples or shrines. And I say that, just as springs mark sacred ground, so also do petroglyphs. That's what I say. And just as in ancient Greece, where there were hundreds of little temples and shrines, hundreds of sacred sites, but one and only one Delphi, so also, in the North Fork American, there is only one Wabena Point.

Wabena Point is in the Royal Gorge, on the very tiptop of the promontory dividing Wabena Canyon from the North Fork itself. Snow Mountain looms across the North Fork, rising 4000 feet above the white waterfalls in the Gorge, and Devils Peak is seen end-on, a narrow black spike of rock it seems, with two owl-like ears.

It may take quite a few visits to Wabena Point to really get it. Wait for the shadows to lengthen, do not go there at midday! I have slept out there on the clifftops, and made many a day trip, over the past thirty years. It is not always possible, especially with other people present, to find my own heart and open my own ears to the song.

I could long for a thousand years to share what I feel there, those few special times, but longing doesn't make it so.

Beware of people who are busy. They have no place on those magic cliffs. Wabena Point is Delphi, and the North Fork – canyon, river, cliff and waterfall alike – is The Goddess.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

In tow, his 19 year old daughter, Mirabai, smart and articulate beyond her years, full of verve and energy. And 21-year-old Nate, a great “kid” with his “head screwed properly on his shoulders” – that’s a compliment, Nate! – who's a real billy-goat of a rock hopper and supreme daredevil on the cliffs and son of another good friend of Russell’s who couldn’t make it.

.jpg)

And beautiful Gay, Russell’s love of his life and mother of his two kids, Janet and Greg, who couldn’t come; and soft-spoken, genial Tom Peterson, hiker / wildman from the gold country around Georgetown, and author of the scofflaw tract, Trespasser's Paradise.

.jpg)

All fine mercurial characters, including Ron Gould, former software computer whiz who left behind his Silicon Snake Oil life years ago, his ol’ Kentucky tail-bangin’ partner, Otis, and your correspondent and instigator of the memorial outing, Gambolin’ Man.

.jpg)

In a tenebrous sky gravid with rain clouds hovering ominously – please blow over! – we strap on our packs and prepare to hit the trail. Gay approaches and asks if I have any spare room, handing me a cigarette Tops container. Huh?

.jpg)

Then it dawns on me that she’s extending the privilege and honor to me of carrying a cache of Russell’s ashes down to the river, to a place he considered one of the most amazing and scenic parts of the North Fork – his "echoing, echoing, all-reflecting canyon of canyons" – for a rite of sprinkling and invocation.

.jpg)

I am deeply touched and remove my pack to find a place for the container, then hoist it on my frame, and we all begin the long, slow march down, down, down, into the canyon. I can't believe I am carrying Russell’s remains! I feel his presence, his spiritual weight bearing down on me, with each step of the way.

.jpg)

The well-graded trail (a rarity for upper North Fork trail systems) wastes no time dropping down over the course of 23 switchbacks and three miles or so, affording spectacular views – despite the cloudiness – before disappearing under the thick cover of oak and fir forest.

.jpg)

Some of these giants are downed making for strenuous obstacle laden exercises to get up and over their bulky trunks. Nearly two-thirds of the way down, we come to a great wash-out, a gaping schism in the earth caused by some destructive pluvial forces that struck in 1997 and cleaved the land wide open.

.jpg)

We’re left with little choice but to rappel 75 ft. down the unstable slide wall. Three ropes are attached to a tree and so one by one we each carefully thread our way down with our cumbersome packs, dislodging rocks and holding our breath as they tumble and crash far below . . . one mis-step can spell a broken limb or some serious bruising.

.jpg)

Well, it isn't as bad as it looks and we all make it down safely, take a rest, and then make our way carefully down the treacherous rock-strewn gully to another set of ropes leading back up to the trail. Ron and Otis have to find a different way down, which they succeed in doing owing to their route-finding, bushwhacking prowess.

.jpg)

Before climbing up and out of this fissure, we waylay at a bubbling freshet emerging from a hole in the ground, offering us gulp after gulp of nature’s finest, purest, sweetest water imaginable.

.jpg)

Thankfully, we’re most of the way down, just a few more winding twists and turns through old growth forest and increasingly bigger rock gardens, until finally the trail levels and drops us off at the river – hallelujah!

.jpg)

What a beautiful river!

.jpg)

The forest service has built a bridge over a tight gorge no wider than ten feet and in one place the river squeezes through the granite walls in a three feet wide extremely narrow chasm.

.jpg)

The water level is rather low compared to pictures I've seen during spring melt-off, yet still the river's discharge is mighty, powerful, hypnotically engaging, as it churns through this mini-gorge before abruptly making a right angle, 90 degree turn into a fairytale pool of deep, cold celadon colored water:

.jpg)

A classic North Fork pool!

.jpg)

It's so inviting I can hardly wait to jump in!

Here, where Palisade Creek dumps its trickling effluence into the North Fork, we seek out a perfect campsite above the rocky banks.

.jpg)

Each of us finds our own particular patch to set up tent or ground cover – mine beneath a fairy ring of a dozen gnarled live oak trees perhaps 150 years old, stunted in height owing to the sparse soil conditions.

.jpg)

Throwing my stuff down under this arboreal umbrella, I waste no time in stripping naked and jumping into the “pool of cold fire” – Russell's name for such icily refreshing dipping holes. Despite being hot and sweaty, I'm in and out in short order, my body tingling with pinprick cold frissons.

.jpg)

I prostrate myself on sun-baked slabbage, at once soft and hard, and revel in the sheer aaaaaaah-ness of it all, releasing a deep, soulful sigh . . . my first immersion this season in the rejuvenating waters of the canyon.

.jpg)

Something John Muir wrote truly captures the essence of my sans souci state of mind, body and soul at this precious moment:

.jpg)

"Choked in the sediments of society, so tired of the world, here your carnal incrustations melt off, and your soul breathe deep and free in God's shoreless atmosphere of beauty and love."

.jpg)

Our riverside camping site is one of the best I’ve ever had, with plenty of surprisingly comfortable high-backed rock (not rocking!) chairs around a big fire ring, shady tree cover, and ample places to evacuate bodily solids and fluids.

.jpg)

And what fine, fine views of the river, the lichen walled escarpments of the eastern face of Snow Mountain, and high, rugged, granite-topped cliffs on meadowy mountains, are enjoyed no matter which way you position yourself.

.jpg)

For the next three days, we will eat heartily, engage in witty banter and scintillating conversation, enjoy the smokeless warmth and company of manzanita wood fires, and sleep and dream with the animals of the forest.

.jpg)

The river meanders and cascades through fingerling channels and drops over sculpted ledges, as it approaches the smooth lip of a massive overhang – welcome to the 65 ft. plunger known as Palisade Falls, or, as it is also called, Rattlesnake Falls.

.jpg)

During high flow, it is a thunderous curtain of white water gushing torrentially to its deep, dark pool, but now, late in summer, it seems relatively tame, but no less awe-inspiring, enough so to keep me back on my haunches a safe distance for fear of being swept over or falling far below into the black shadowy waters.

.JPG)

.jpg)

One thousand one, one thousand two, one thousand three – KERPLASH! He does it! And he’s ready to do it again!

.jpg)

He friskily swims to a ledge, scrambles up and around to the top, and repeats his feat of air borne prowess, but unlike at other jump spots, he doesn’t muster up enough courage to do a flip here – it might easily be a 75 ft. jump. Still, gotta give the boy his props! Ah, to be young and 21 and fearless and immortal again, what I wouldn't give.

.jpg)

In the late afternoon, with shadows creeping up the mountainsides, and vestiges of sunlight breaking through the overcast pall, we reverently take Russell’s ashes to the mirrorlike pool to bid him farewell, to cast his powdery remains into the river where he will merge with it for all eternity.

.jpg)

It is a hushed, somber moment, but also one of ineffable joy as we gather to release him down river, knowing his spirit is alive here, palpably infusing with our own and the river’s and the sky's. In turn, we each sprinkle Russell into the water, his ashy body discorporating in thin air and then settling on the water’s surface and floating gently away with the current.

.jpg)

I bid our good, dear, kind friend, who was snatched from this world too early:

.jpg)

“Adios, safe tidings, have a merry journey downstream, see you in the next world, Russell!”

.jpg)

.jpg)

"I carry your heart with me (I carry it in my heart)."

.jpg)

The slow-motion setting of the sun creates a golden hue over Snow Mountain and the land, followed by a prolonged alpenglow effect that spreads its amber and lavender wings across a painterly firmament, leaving us agasp and absorbed in our own thoughts and meditations at such deliquescent crepuscular beauty.

.jpg)

Then, quietly, night falls. Stars appear, but not for long. A gradual hint of Albion glow from behind the mountain, soon full-on moonshine as the bright orb rises high over the arete and pours forth its soft luminescence down onto our surroundings casting candlelit apparitions and spooky shadows.

.jpg)

In the middle of the night, I crawl out of my sleeping bag and half-stumble down to river’s edge to bask in the prolonged gloaming – a transcendent aura radiates, moonshadow reflecting chalky white boulders in the still slate water.

.jpg)

Gazing up to the high precipices of mystical Snow Mountain, I feel as though I’m dreaming a dream of dreaming a dream of gazing up at an illusory peak. The sound of crickets, a whisper of wind rustling in the oak boughs heightens my senses, no other sound now, except the gurgling song of moonlit soaked waters.

.jpg)

Suddenly Otis is up and barking, running in circles, sniffing madly – he's picked up the scent, no doubt, of a bear out for a moonlight stroll herself. I strain to hear her tramping on the opposite bank, but nothing. Bears (uncorrupt ones, that is) will go to great lengths to avoid humans, as will most animals in the wild.

.jpg)

Earlier, I assured some skeptical members of the group that hanging food as a precaution against predatory bears is unnecessary in the canyon . . . and later, on discovering an unraided stash of sausages and rotten meat at a nearby campsite, my hunches are proven correct. (Now, pesky little squirrels are another matter entirely!)

.jpg)

The next morning, rallying the troops, we set off in fine tone (as John Muir liked to say before a Sierra ramble) for a level III gorge scramble, to explore the sights down river, itching for action / adventure, eager to see what lay beyond each bend and curve.

.jpg)

Past Rattlesnake Falls, the river opens up for a straight-away half-mile stretch where the boulder hopping is challenging and fun, and sidewalk-like slabs of granite bedrock allow for easy strolling right along the gently flowing river.

.jpg)

Huge boulders choke the stream – one entire cliff face has fallen to the river from on high creating a concatenation of boxcar-sized boulders I coin the train wreck. (Only Ron catches that one!)

.jpg)

Along the river’s edge, we encounter great cedars, big leaf maples, alders, Kellogg’s black oak, canyon live oak, tangles of manzanita brush, aromatic bay laurel, and the occasional cottonwood, along with the ever-present poison oak and assorted other plants flourishing in perhaps the richest biota in the Sierras.

.jpg)

It's a smorgasbord of victuals for the many animals who pass this way and call it home. Rounding a bend, we’re forced to climb high over cliffs and dodge gigantic boulders and trod over gleaming slabs of granite nearly snow-blinding us, and then – WOW! – another great waterfall! – this one tumbling 30 ft. over a granite dike feature called Curtain Falls.

.jpg)

Before you know it, Nate jumps a dangerous several feet off the cliff to gain better purchase at the lip of the falls, and – one, two, three – from there he plummets, this time a fearless somersault into the deep pool below! It’s a most impressive move, pretty doable, but I must admit, I cannot bring myself to fling myself off the edge of the world like that.

.jpg)

We stop, gawk, admire, and then make our way down and around and over many earthy obstacles to find ourselves now at the base of the falls for a great vantage point. We could stop here for the day, but we press onward, trying to make it all the way to Wabena Falls, still another mile or more downstream.

.jpg)

Trying to get past what Russell referred to as:

.jpg)

" . . . the distinctive contact zone between the metavolcanic Tuttle Lake Formation of Snow Mountain on the west, and the granite of Palisade Creek on the east."

.jpg)

Were he here, no doubt we would be waylaid for half an hour while he held forth lecturing on the nuances of the contact zone.

Snow Mountain consumes our field of vision and captivates our imaginations the entire way downstream.

.jpg)

From our camp perspective, the mountain looms as though composed of a giant bulk of solid earth, a massive formation rising 8000 ft. above sea level. But approaching ever closer, its aspect changes, its visage morphs, into a cluster of mountains, each its own ragged, craggy self, rent apart by gargantuan defiles, cleft into individual sun-blasted spires and pinnacles.

.jpg)

Suddenly, it's no longer a solitary agglomeration, but an eco-system of several distinct mountains with unattainable peaks.

.jpg)

Noting a long gash down its back side, Russell dubbed the mighty couloir “Cirque Creek” – he and Ron had witnessed a torrential rivulet of water streaming down this gully in days past, but today it is mostly dry with the exception of a slickrock patch glistening with algid drippings of the last vestiges of spring run-off.

.jpg)

We’re now approaching another incredible two-tiered cascade that Russell nicknamed Petroglyph Falls, because from way high up at Wabena Point you can just barely spot this tiny insignificant looking feature.

.jpg)

But now, down on the river, the falls looms incredibly large and obstacle laden, and forces our approach up and over a cliff and through a long stretch of wicked poison oak-laced scree broken up into millions of pieces of sharp rocks that leave a few of us with some nasty souvenirs in the form of scrapes, cuts, and nicks.

.jpg)

Not to mention some of the crew is suffering from blisters which will impede further progress down the river.

We stop at Petroglyph Falls and take up perfect viewing positions atop a large, flat boulder to eat, recuperate, swim about, and marvel and gawk at our stupendous surroundings.

.jpg)

Oh, but would Russell be impressed and full of wonder! Oh, how he would soak it all up with irrepressible enthusiasm – rambling on poetically and interspersing it with a geomorphological lecture.

.jpg)

Taking stock of our beat-up conditions and mulling over the prospect of a long trek back upriver, we decide that Wabena Falls ain't goin' nowhere.

.jpg)

It will doubtless still be there on our next visit. Besides, we reason, we’ve already been treated to a myriad of incredible sights, so the consensus – What? You've seen one waterfall, you've seen them all? – is to enjoy a few precious moments at Petroglyph Falls and then make our way leisurely back upriver.

.jpg)

Everyone seems relieved, if just a tad disappointed at the decision, for we all had our hearts set on taking in all three of the lower gorge's great waterfalls.

Two hours, several ouzels, a few sister butterflies, and one rattlesnake later, we get back to camp, sore, bloodied and bruised (some of us).

.jpg)

The rest of the day is lazy, each lost in our own worlds, sitting around nursing our wounds, reading, talking, swimming and sunbathing, generally relaxing, taking it easy and greatly enjoying the slow, languorous passage of timelessness.

.jpg)

Eventually, the day turns to evening, and it's more of same – eating, talking, sharing stories of adventures past, learning more of each other's interests and desires, reminiscing about Russell, and sitting in silent contemplation, ruminating over the day's events, rehashing in our minds all the wonders we have witnessed in so short a time.

.jpg)

The day's rigors, though, have taken a toll and I'm exhausted – bidding everyone buenas noches, I'm soon fast asleep in my bag, enjoying a sound night's sleep, replete with hallucinogenic vivid dreams, barely aware of the glaring moon, or Otis' midnight barking at real or imagined bears on the prowl.

.jpg)

And then – sleep now being over-rated – I'm up at the crack of dawn to greet pink sunlight spilling over Snow Mountain – precious sight! – and get a fire going, make coffee, all to maximize waking consciousness on this, our last day down on the river.

.jpg)

How difficult to leave this place, knowing I won’t be down in these parts for a long time. With a tinge of regret, I wish I could remain here forever, never go back.

.jpg)

It's so beautiful, so peaceful, this is where I belong, here with Russell in his echoing canyon of canyons! Well, silly me, my time will come soon enough, and I hope, too, with bittersweet sighs, that when that day comes my friends and loved ones will tote my ashes here to scatter in the wind and become one with the river, sky, trees, rocks.

.jpg)

For now, though, it's time to say good-bye . . . time to strap on my pack and make the climb out. We gather up some garbage (not the rotten meat!) left by disrespectful hikers at the nearby campsite, and hit the trail, immediately climbing, up, up, and up.

.jpg)

Yes, hiking uphill – gaining elevation – is always easier than its opposite – except at the giant wash-out, where we now have to rappel UP that sucker! It's twice as hard as bouncing down it, but we all grunt our way up without incident.

.jpg)

Ron and Otis, though, make their way from the bottom of the ravine up the side of the ledge through thick forest laden with impediments and obstacles – clearly taking it out of them. Now, regrouped, we break into two groups.

.jpg)

I'm fueled by adrenaline, trying to keep up the relentless pace of the two young ‘uns, who are hauling ass out front and making great time. Yeah, I'll feel the pain in my feet later on, but such is the price of admission to the Mother of all Canyons.

.jpg)

Limping, limping, the final few hundred yards . . . what a great relief to finally attain topside elevation, see the vehicles, drop my pack, strip off sweaty clothes, throw off my boots, and take in the last views of Snow Mountain and the Sierra Nevada backdrop.

.jpg)

Eventually the rest of the crew straggles up – Otis leading the charge and then dropping dead-tired in the middle of the road, tongue hanging out and panting heavily – and we all high-five Ron as he breaks out some cold beer and fresh cantaloupe from a cooler!

.jpg)

It's oh-so-refreshing and we're all giddy, if a bit sore and wasted (I'll speak for myself) from the heat of the day and the tremendous efforts incurred climbing out of the canyon.

.jpg)

I turn to Gay as though to say, "We did it!"

.jpg)

She smiles, revealing a secret knowledge and shared wisdom that such an endeavor certainly takes its toll, or Towle-like strength, courage and determination.

.jpg)

"You know you've really been somewhere special for all the hard work required to get down and back up this canyon."

.JPG)

That's why Russell so cherished the small fraternity of spirited and dedicated people who willingly endure the joyous tortures, for the rewards only come to those few, as he liked to say:

" . . . who will dare the descent, to swim the magic pools, herd the ouzels, and bother the rattlesnakes."

.jpg)

Honoring Russell Towle:

Check out more Gambolin' Man adventures in California's great American River canyons:

.jpg)

Grab a beer & settle in for some live (but shaky!) footage deep in the heart of NORTH FORK AMERICAN RIVER canyon country:

Photos of Russell Towle courtesy of Catherine "CanyonSpirit" O'Riley

Photo of Gambolin' Man rappelling with Otis looking on courtesy of Ron Gould

Photo of Heath Falls courtesy of Russell Towle

To purchase North Fork Trails & Trespasser's Paradise, contact Gambolin' Man