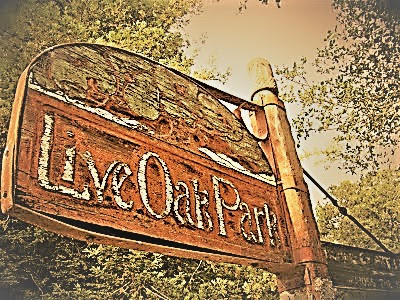

LIVE OAK PARK: Meditative Strolling & Reflective Lolling in the Wild (& Urban) Environs of Berkeley's First "Nature Park"

A small parcel of gently sloping land, cleft by a small ravine, is nestled in a pretty neighborhood two minutes away on foot from my North Berkeley residence – and a creek runs through it.

Not just any creek, but Codornices Creek, named after the many California quail who once graced the area. Codornices Creek is one of dozens of primordial East Bay Hill streams that used to run free and easy, emptying into once prevalent brackish marshes and sloughs along the vast Bay shoreline.

Most of the East Bay Hill streams and their tributaries were long ago concretized over, buried, relegated invisible, but progressively, city planners and environmentalists are restoring our charming little creeks to see the light of day once again.

Live Oak Park, through which Codornices Creek runs for about – I don't know – maybe a total of 300 yards – is Berkeley’s first “nature park”, so designated in 1914 by the Berkeley City Council at a time when Berkeley took up the gauntlet and ascribed to the guiding principles and philosophy of the “City Beautiful Movement” – urban beautification campaigns aimed at promoting “a harmonious social order that would increase the quality of life.” (Wikipedia)

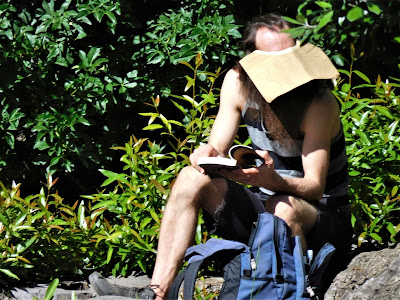

They got that right. Without Live Oak Park a heartbeat away from my doorstep, my quality of life would be greatly diminished. Especially after forsaking a car two years ago, having this slice of beautification at my instant disposal is a welcome gift of relief after a hectic day at the office, or whenever I'm feeling restless, stressed, or just homebound and in need of a quick "nature park" fix.

Over the past forty years, Codornices Creek has been daylighted – outed! Most of its entire journey to the bay can now be enjoyed and admired by nature-starved urban dwellers, by appreciative deer who come to sip from its waters, by raccoons who come to claw out crayfish, and by birds who find sanctuary and shelter along its shadier stretches.

Many years ago, though, residents of the hills despoiled their little gem with raw sewage and whatever else was deemed dumpable, and officials thought it in the best interests of public health to just bury the effluvia the creek had become under roads and sidewalks. Out of sight, out of mind.

Such an easy thing to mindlessly destroy a beautiful natural habitat . . . but, of course, to quote T. C. Boyle in When the Killing's Done:

"Restoring an ecosystem is never easy."

Today, after much tireless work by advocates and friends of Codornices Creek, the little brook is, without doubt, a precious natural resource, and veritably a pretty sight as it meanders through parks, back yards, neighborhoods and industrial areas.

But I'm guessing that only the devout worshippers among us of the small, overlooked and unheralded might find this simple city creek worth crowing about. I hope I'm wrong. I hope people do look beyond the seeming mundane and get excited about the creek's presence, notice it, pay it homage.

It's easy to overlook its charms; after all, apart from being an overly familiar backdrop, it's not a powerful Sierra river worth gawking over, or some big north country trout stream to get worked up about; it isn't in a designated wilderness area; and by all means it lacks the drama and scale and magnitude one wants in their wet dream water scenery.

(Although upstream, on private property, there exists a multi-tiered sixty foot waterfall in a small canyon that is as impressive as anything outside of Mount Diablo State Park or Marin County. Seriously.)

So why would anyone gush over something so commonplace and unremarkable?

Because it is!

Because Codornices Creek is what it is – a modest, humble, tiny ribbon of water, about three to five feet in breadth, flowing through two densely populated East Bay cities.

Certainly not to the resurgent steelhead who have come home to nest; not to the deer, raccoon, squirrels, birds (and foxes, coyotes and – yes! – mountain lions!) who rely on its cool cache of water and other "mean and lowly things" to munch on and sustain their living populations hidden in gaps where the urban / profane intersects with the natural / sacred (the so-called ecotone).

And, most definitely not to Gambolin' Man and to those of a similar heart-soul-mindset who realize, like Ralph Waldo Emerson, that:

" . . . the invariable mark of wisdom is to see the miraculous in the common."

Who understand, like Paulo Coelho, that:

" . . . each day brings a miracle of its own. It's just a matter of paying attention to this miracle."

Who, like Frederick Franck, grok the:

" . . . extraordinary, the sheer miracle of the branching of a tree, the structure of a dandelion's seed puff."

And who resonate with Edward Weston's photographic dictum:

" . . . not searching for unusual subject matter, but making the commonplace unusual."

Because Codornices Creek is what it is.

Originating in the central Berkeley Hills 900 feet up, it drains an area of about one square mile, and flows nearly three miles to San Pablo Bay through the cities of Berkeley and Albany.

Although much of the watershed evaporates, Codornices Creek never dries up, awing (some of us) with a perennial flow – albeit a trickle in places during prolonged months of zero precipitation.

Many, if not most, hill creeks dry up within weeks or days of downpours, while a select few owe their existences to ideal geological conditions that collect and store rainfall.

Slam-dunk miracle!

I've often wondered how long it would take for that well to run dry and what is the mechanism by which water is gradually, but continually, released – is it by means of gravity? suction? seepage? sponge-action?

Such big mysteries in seemingly little things!

But thank heavens, it always rains just in time to replenish the cisterns and keep the creek a viable habitat to attract ocean-venturing (and threatened) steelhead trout – Oncorhynchus mykiss – to their aboriginal spawning grounds farther downstream.

Imagine! Our little neighborhood creek is healthy enough, to the extent possible, to play out the primal ritual after so many years of being shut off from the cycle vital for anadromous fish – fish that live in the ocean mostly, and breed in fresh water – to carry on and survive. Give Mother Nature half a chance, and she will rebound.

We're witnessing this up and down coastal Northern California where rehabilitation efforts to return spawning creeks to their wild state are paying big dividends for increased populations of coho and steelhead.

We (can only) hope.

For millennia, native Huichin peoples established their village life in the shady lushness of Codornices Creek and reaped the bounty effortlessly – trout, shellfish, salmon, deer, berries, herbs, and acorns from the many varieties of oak trees kept their baskets and larders overflowing.

It’s easy to idealize their existence and imagine a time when aboriginal people lived traditionally off the land right here in Live Oak Park, co-existing peacefully, trading with their Ohlone relatives – a proud, quick-witted people whose every need in this Land o' Plenty was met by a proliferation of abundant natural resources and a cornucopia of plentiful edible foodstuffs.

All of which enabled them to achieve heights of cultural sophistication, as they were able to devote so much more of their time engaged in – not survival pursuits – but storytelling, dancing, arts, rituals and myth-making, and family cohesion and community harmony.

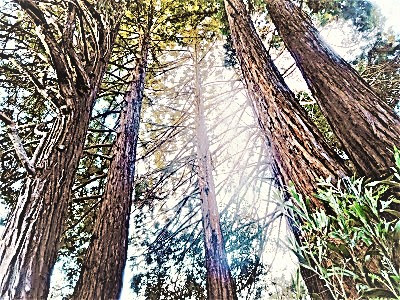

Sensual, earthy aromas pulsate in the brain – dewy tree branches, the smell of laurel in mud, heady, pungent redwood duff. The spellbinding rhythm of churning, melodious water burbling through Live Oak Park in a snaky bed framed by 100 ft. tall Redwoods entrances and captivates. The roar and commotion won't last long, maybe twenty-four hours.

I stand motionless on a big redwood burl and gaze mindlessly into the foaming and churning water, oblivious to everything and nothing. The dry familiarity of the commonplace has suddenly become a glistening, exotic, almost unrecognizable world unto its own . . . all because of a little rain.

A changed perspective also helps. I get right down to the creek's little shore, looking beyond the obvious observations, and begin examining things from a new angle, a different perch. At once, I'm in Live Oak Park, and I am not. The sensation of being lost in a private wilderness sanctuary is enhanced, and very real.

On a lonesome late afternoon, lured by the Siren call of a rainstorm, with barely anyone about, and the creek's mighty little roar drowning out the noxious noises of city life, it can surely seem like you're transported to another realm. Returning to an all too familiar scene, it turns out I really am getting to know the place for the first time, seeing it, truly, through different lenses.

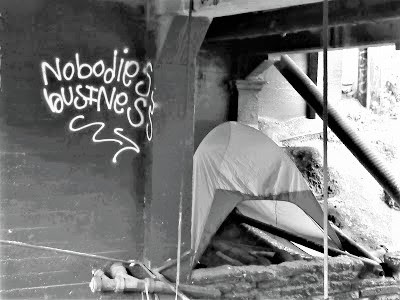

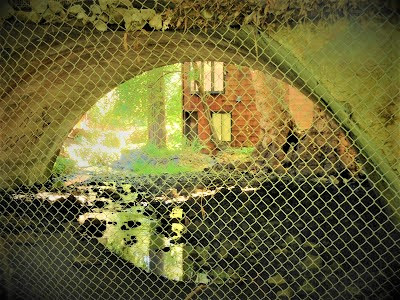

Codornices Creek is not what it appears to be. Live Oak Park is an amalgamation of pure, sweet nature and grim urbanity. The contrast can be subtle, the dichotomy unsettling, when urban chaos and natural sublimity intermingle and intersect.

But when you're lost in your little world, the industrial world can seem nonexistent. I'm entranced at water’s edge, admiring colorful rocks and tangled roots. There is no one about (who wants to be in this horrible pouring rain for heaven’s sake?), nothing going on except me and turbid water surging beneath a towering tree canopy.

Then I look up and spot ugly graffiti and a beer bottle some teenagers tossed several days ago – a jolting reminder that I’m in the city, not lost in my imagined wilderness area.

Then, moving along, my attention shifts to a white flowering tree; squirrels prance high atop in branches, ravens' screeches pierce the air as four of them land in a tree top. I am grabbed by how the creek cuts a sinuous course – a perfect S-curve – through the red needle covered flooring of the understory of redwood trees.

Then I turn to focus on a grove of aromatic bay trees and flowering dogwoods growing tall and proud alongside a steep embankment of the creek, a willowy stretch showcasing a set of snappy riffles sing-songing over small rocks, instantly cradling me back into the arms of nature.

Then, I look up and see a dog-walker coming by, a woman with a panicky, hurried look to her stroll – shuffling along, head down, not at all enjoying the inclement weather. The beauty and raw power of the resurgent creek means absolutely nothing to her. Her dog, leashed, wants to run.

Urban constraints vs. natural flows. Further along, I check out in closer detail than I ever have the elegant old stone fireplace, completed in 1917, when Live Oak Park was one of the few gathering places for people to come together and experience community; back then, it hosted more than 10,000 people and 300 gatherings a year.

How many times have I felt compelled to leave the park owing to suffocating and lingering smoke from a barbecue pit? Stinky, cloying smoke that just seems to hang in the air above Live Oak's spacious lawns. And to think what it does to our little birdy friends' tiny lungs!

But, alas, I realize I'm a lone dissenter here, way out of line, and certainly in the strict minority of people who decry barbecues as violating our right to enjoy non-polluted air. Because it's so ingrained in our Cave Man DNA, it's doubtful laws will ever be passed to prohibit or curtail barbecuing in public places.

WAIT! On second thought . . . NEGATIVE!

But urban afflictions are prevalent – the Banksy wannabes, who uglify walls and spaces with their street "art" (very little of it is any good); the frequent bad air from burning wood and charcoal; and the unsightly homeless men and women who find refuge under tunnel overhangs, in bridge nooks and crannies, and on cold days, at the barbecue pits where the impoverished build fires to warm themselves.

Can't blame 'em, I don't suppose.

It will always be an urban park, replete with urban ills, and defined by people doing mostly urban things.

But if you look deeper and happen to visit on a day when no one's around, you will enjoy its subtle splendors in peace and solitude.

MAY CODORNICES CREEK SURVIVE

AND THRIVE FOR ALL TIME!

Read Gambolin' Man's effusive write-up / love letter to the creek that runs from the Berkeley Hills to the San Francisco Bay:

BONUS VIDEOS of a beloved places in North Berkeley:

Read more about Gambolin' Man's premier birding experiences at Live Oak Park, Codornices Park, & at many other parks in the Berkeley Hills, flats & marshlands: