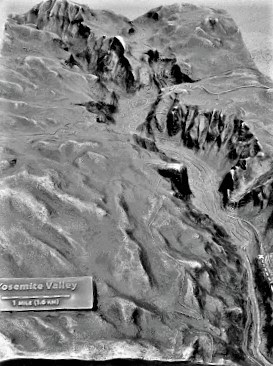

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK: Ascending the Steep John Muir Trail to Vernal Fall for a Teasing Glimpse at the World-Famous Back Country Wilderness

We didn't exactly make it to Yosemite National Park in the style that John Muir might have preferred – that is, walking from Oakland over the course of many moons where the famed stalwart and defender of nature sought out:

" . . . any place that is wild."

His legendary saunter to him up and over Mount Diablo and the Pacheco Pass, across a flowery sea of the great Central Plain, and on into ever wilder foothills, to arrive in pristine glory at the doorstep of the cathedral-like valley that greeted the peripatetic soul-searcher. His astonished impression could barely be put into words, but he noted it was:

" . . . by far the grandest of all the special temples of Nature I was ever permitted to enter."

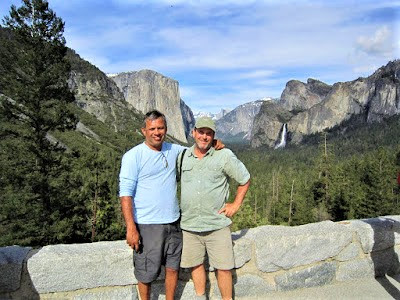

No, we got there the way five million tourists annually make the modern-day pilgrimage – by gas-guzzling vehicle over cleverly engineered mountain highways. At least, though, we arrived early on a Tuesday morning before the campers’ tent flaps opened.

Before the swarming crowds poured in via three different access points, before the sun had a chance to climb over stupendous walls of clean, naked granite and spill soft radiant light onto the green carpet of the valley floor.

It was an auspicious beginning to our day, having, if only for a couple of early morning hours, Yosemite’s incomparable wonders all to ourselves, it seemed, before the masses descended.

Huge off-putting crowds of gawkers and outdoor enthusiasts capable of swelling to 20,000 fleece and polyester clad, pole-wielding, camera-toting people per day, filling the valley as though it were a free-for-all entertainment zone, or more aptly, a buzzing formicary of non-stop scurrying activity.

It was 1984 when I last visited Yosemite Valley proper, way back when, when I was a cocky young whippersnapper able to haul in a sixty-pound pack as though it were a sack of cotton. I veritably jogged the rugged eight-plus miles to Half Dome and scampered up its dizzying near vertical slickrock face like nobody's business.

And thankfully I didn't have to go out on a macho limb to prove it to myself or to my hiking partner and long-time amigo, Javier from Acapulco, because the cables were down and the harrowing, heavily trafficked 4800 ft. route up to Half Dome’s summit was closed due to lingering snowpack.

That meant the farthest we could hope to traverse in the fabled wilderness of Yosemite’s back country was to the top of Nevada Fall – ha, an easy 2000 ft. / 2.9-mile (one-way) frolic from the Nature Center at Happy Isles.

Turns out, because we were so time-poor and at least one of us was out of shape, and the other had a nagging foot injury, and mainly because we’re both staring down the backside of our sixth decade – we only made it to the top of Vernal Fall, a mile below.

Make that "only made it" in quotation marks, because that little nothing of a short hike happens to be one butt-whompin' 1000 ft. / 1.5-mile uphill trudge that tested the limits of our endurance.

I'll speak for myself, never one to adulate humanity in droves; as for Javier, my contemplative amigo seemed stunned into reverential silence by the awesome beauty engulfing him on all sides. Tomas, he proclaimed afterwards, this place is more impressive and beautiful even than Foz de Iguaçu!

Forget about the people! Look around you!

Ah, Yosemite, Yosemite!

How can I possibly know and experience and love you the way John Muir or any number of nineteenth and early twentieth century romantics, artists, and photographers did, or even my old self from the early eighties, when crowds were non-existent compared to what they are today.

How can I possibly? How can anyone when it's all been turned into a barely tolerable amusement park?

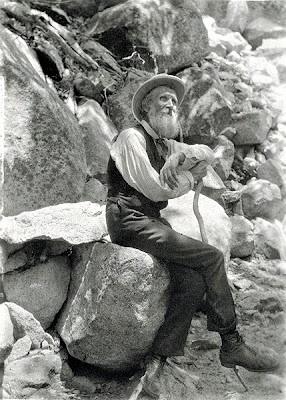

Yes, back in day-day, when Muir spent his time gambolin' about without a care or worry on Earth in his Meadows and Forests of Heaven; traipsin' about exploring high ice-clad peaks; and scaling knife-edge ridges on three-night excursions with little more than a tin cup for tea and a crust of bread for sustenance.

Back in "the airly days" when he laced up his old-old-school shoes and snatched up barely a coat to keep him warm, Muir spent only the better part of a half dozen intermittent years in Yosemite, ensconced in a hand-hewn sugar pine and cedar cabin with a drop-dead gorgeous view of Upper and Lower Yosemite Fall at his doorstep.

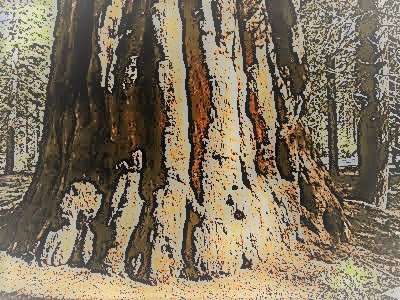

One morning, we stood there, in the very ghost of the old cabin’s foundations, as though in a fairy ring of a giant sequoia that once existed, soaking in the vibe, imagining the scene 140 years ago when Muir, he of the Thoreau and Emerson school of rustication and immersion in nature, wrote at a simple desk with an arch of ferns entwined with the gurgling chorus of the diverted creek running right beneath his feet.

There he'd pass idle hours and do-nothing days in stony contemplation of nature’s softer features but particularly the dynamic forces that saturated:

“ . . . every fibre of the body and soul, dwelling in us and with us, like holy spirits, through all of our after-deaths and after-lives.”

Yosemite was Muir's temple, his refuge, his big wild place of redoubt that filled his heart and soul with nature’s good tidings.

But even Muir and his transcendental brethren who so deeply appreciated the ethereal qualities and spiritual sanctity of the imponderable beauty of this otherworldly landscape could not have known or loved or experienced the place as intimately or knowledgably as did the aboriginal peoples.

In trying to imagine the story of Yosemite, it must begin with the Miwok-Paiute people, the Ahwahneechee, who lived in the “deep, grassy valley” called Ahwahnee, meaning “place of a gaping mouth”.

The name Yosemite itself is believed to be either a garbled translation of Uzumati, Grizzly Bear, or thought to be a corruption of “Yo-che-ma-te” (some among them are killers). Let’s go with Grizzly Bear, since the latter obviously is a derogatory epithet, like Anasazi is considered to be by modern Pueblo peoples in the Southwest.

The Grizzly Bear People of the place of the gaping mouth – otherwise known as the Ahwahneechee – surely were deeply spiritual by nature, living as they did in a heavenly garden of paradise, even though the first white men believed them to be superstitious and unkempt savages incapable of perceiving God’s bounteous glory and beauty.

It was believed only the white man could be infused with an exalted sense of spiritual transcendence and giddy joy at nature’s grandiose revelations on such a monumental scale as never before witnessed by civilized man.

Native peoples, it must be understood – and no way could the culturally imperious, Manifest Destiny-driven mind of the nineteenth century grok it – were deeply attached to their land, loved and respected it like a family member or the deer and bear and salmon and trees and plants that provided food and shelter for them.

Without written language, they just had different ways of expressing the same rapturous feelings, through sacred ceremony, ritual chant, and communal prayer to almighty Creators.

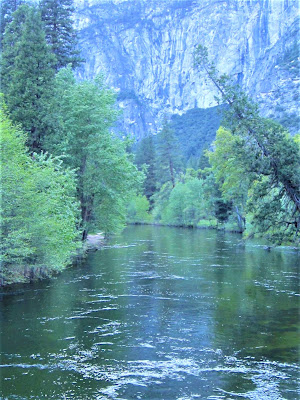

It was in this idyllic setting that the Ahwahneechee encamped in picturesque villages along the Merced River, one of the West’s greatest, flowing lazily through the grand meadow like a liquid stream of diamonds, framed on all sides by celestial-scraping granite formations of (now-named) El Capitan, Sentinel Dome, Cathedral Spires, and Eagle Peak.

It was here – a place Muir described thusly:

" . . . dressed like a garden, sunny meadows here and there, and groves of pine and oak; the river of Mercy sweeping in majesty through the midst of them and flashing back the sunbeams."

Here, where the peaceful Ahwahneechee gathered in small tribal bands, to live as their ancestors did in a perfect harmonious relationship with the timeless rhythms of the cosmos, the comings and goings of seasons, with Mother Nature.

They controlled the natural ecology in beneficent ways with periodic burnings to clear out brush and saplings. In their pilgrimages to and fro, they collected acorns from abundant stands of black oak, storing bushels of them for processing into mush or hot cakes, and trading them for turquoise, feathers, and salt with itinerant tribes.

Until one day in 1851, the first white people made their way into the valley. (Paradise Breeched.) They were not wayward stragglers hoping to break bread with friendly natives; they were not lost and weary strangers in search of hospitality and the sharing of the peace pipe.

No sir, this was the Mariposa Battalion, hired guns of California's fledgling government, conscripted to round up or, if necessary, by legal use of force kill the red-skinned savages responsible for plundering and raiding lucrative trading posts on the gold-flushed rivers and creeks of the Sierra foothills.

Ever since gold fever struck the region surrounding Yosemite in 1848-49, destructive and disrespectful prospectors flooded the nooks and crannies of the valleys, polluted the creeks and hunted all the game, pushing the natives into marginal areas, and all but destroying their livelihood and stamping out their way of life.

What choice did the natives have but to defend themselves and their homeland?

Led by Chief Tenaya, a small band of renegade outliers mounted a fierce resistance and did their best to oust – or at least severely pester – the unwanted newcomers.

Unknowingly at this point, they were up against an impossible foe, one who was in the beginning stages of national unified campaign to utterly crush and wipe out all Indian resistance west of the Mississippi.

The contingent rode out to Inspiration Point late one afternoon on March 25, 1851, with Yosemite Valley veiled in a haze of blue mist 3000 ft. below, in search of ragtag rebel Indians.

" . . . none but those who have visited this most wonderful valley, can even imagine the feelings with which I looked upon the view that was there presented. The grandeur of the scene was but softened by the haze that hung over the valley – light as gossamer – and by the clouds which partially dimmed the higher cliffs and mountains. This obscurity of vision but increased the awe with which I beheld it, and as I looked, a peculiar, exalted sensation seemed to fill my whole being, and I found my eyes in tears with emotion."

Bunnell, though, so moved by nature’s sublimity, was no enlightened soul, no lover of the “noble red man” – despite learning their tongue, he despised them and held them in contempt as “graded low down in the scale of humanity.”

Long story short, Savage, Bunnell, Boling, Kuykendall, Dill, Lewis, Brunson and Hailor as Guide, along with the rest of the eighty strong regiment, proceeded into the valley and rounded up as many of the renegades as possible, killing one of Chief Tenaya's sons in the process, and eventually forcibly relocating the captives to concentration camps in the lower foothills. (From which they escaped and had to be rounded up again.)

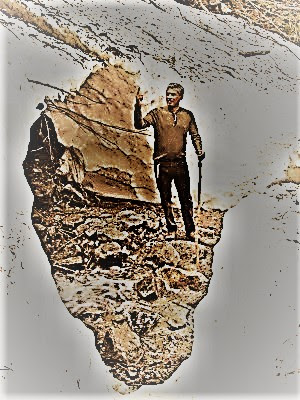

And to this day, there are those that believe Chief Tenaya's (picture above) spirit haunts Yosemite, and the curse lives on with mysterious disappearances and freak accidents.

Such is the sad introduction to the beginning of the white man’s history and occupation of Yosemite Valley presaging the iconic status it holds today worldwide as a place of mind-blowing beauty, a big playground for millions of tourists.

Most of whom cannot fathom the violent smack-down that occurred in order to rid the valley of its original inhabitants and pave the way for inevitable “progress” – protection status, roads, hotels, tourism, commerce – some good, some bad, who’s to say, except that there is bloodshed, dishonor, deception, historical obfuscation and a ton of heartbreak in the deal.

Sadly, that’s the story of our country, too – of most nation-building no matter the historical period – when all’s said and done.

Javier and I had some time to kill, since it was only 7:30 am and the grocery store didn’t open until 9. We had spent the previous night in historic Groveland, an hour outside the park, holed up in a bromantic little B 'n B called Hotel Charlotte right on the main strip across the street from the Iron Door Saloon, the oldest continuously operating bar in California.

We passed a breezy hour listening to Led Zeppelin blasting and drinking hoppy ales and watching the NBA playoffs with some German tourists, good ol’ boys, and country rednecks.

No worries – it would be easy to pass a couple of hours, if all we did was just sit on a park bench and gaze at the peaks, monoliths, and waterfalls. We pulled over to take in the River of Mercy, admiring its early morning reflective beauty.

Oh, our jangled souls soothed by its gentle mien meandering through the valley, in such contrast to the surrounding bald expanses of bare-naked rock piercing the core of our being, and so unlike the wild and tumultuous upper stretches of the river we would later encounter on our hike.

We took a few minutes to leisurely stroll around the meadow and forest grove, transfixed by gentle shafts of sunlight playing optical tricks with swirling water, golden and shiny, or standing back in awe gazing up at the neck-craning facades of gray black granite slabs and innumerable sculptural forms encasing all sides of the valley.

I had truly forgotten how impressive it all is, and little wonder people from all over the world seek it out to inebriate their aesthetic sensibilities and claim a part of it for themselves.

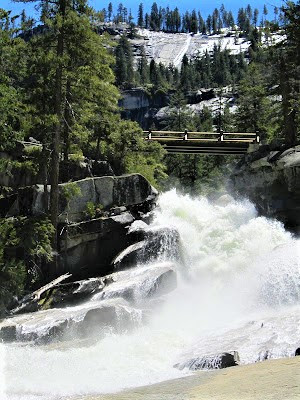

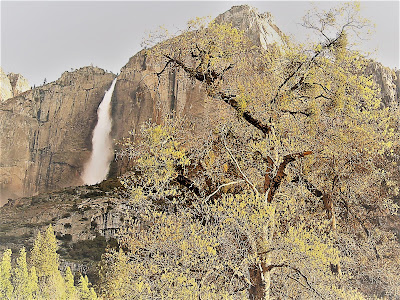

On a slow spin around Northside Drive, we came to a view perhaps the most famous in the park – that caused me to immediately pull over and jump out, gasping in primal delight at the sight of North America's grandest spectacle of falling water – Upper Yosemite Fall.

Acclaimed as the sixth or seventh highest waterfall in the world, it was framed in picture perfect postcard beauty by monumental granite walls and dense pine tree cover. Presenting our astonished visages with the kind of once-in-a-lifetime nature sighting that normally you have to hike in fifteen miles to witness, but not here, where anyone can enjoy the miracle of nature's dynamic forces.

Watching this monster falls pour forth an unimaginable cargo of frothy whitewater over a gigantic lip of carved granite, free falling an astounding 1430 ft., and ranking among the twenty highest falls in the world, it was truly a privilege to stand there in mute testimony to nature's grandest creation.

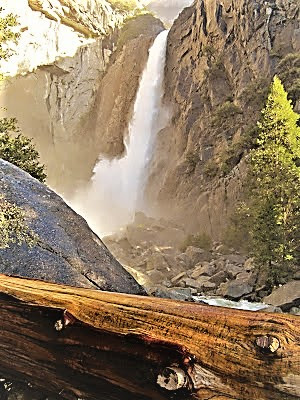

And that was just the upper part of the falls! There's an unseen middle section – known as the Middle Cascades – plunging in a series of five falls nearly 700 ft., and finally, the jaw-dropping 318 ft. Lower Yosemite Fall, equal, nay, surpassing in aesthetic grandeur and dramatic impact affecting my overwhelmed senses owing to the proximity with which we approached and viewed.

Altogether, the plunge is 2425 ft. Now, I’ve seen some waterfalls in my day, but this, why, as Albert D. Richardson ineffably expressed it in his 1867 travelogue, Beyond the Mississippi:

“I shall not attempt to describe it; the subject is too large and my capacity too small.”

Javier was lazing in a patch of sun like a reptile warming up, and I hurriedly shook him out of his mellow reverie:

“Follow me, Indio! We’ve got to get up close and personal for this one!”

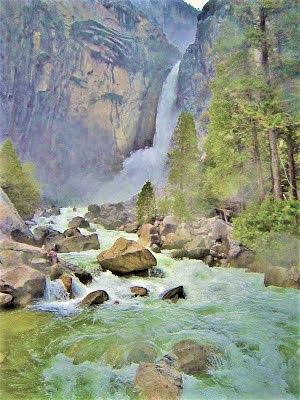

In about ten minutes we came to a bridge over a raging torrent of water – Yosemite Creek! – the released payload from massive jets of spume and spray pouring over the granite walls from so high above it was invisible except for a blue wedge of sky.

With sunlight striking at just the right angle, a thick, multi-hued rainbow appeared above the massive detritus of talus like a mirage from heaven’s playbook of all-time gorgeous images ever witnessed in Mother Nature’s grand pageantry of scenery.

I was moved to near religious ecstasy by the salacious sensuality of the moment – by this overpowering adrenaline-flushing sight! Angling in for a closer look, Javier and I made our way over slippery boulders to a vantage point on the opposite side of the falls, as close as we could possibly get to view the raging, deafening spectacle.

So much water crashing down from on high – creating a perpetual spray of drenching mist, swirling ethereally up and away like wisps of smoke, leaving us both standing there shivering in the morning gloam, faces dripping with icy water, as we simply could not unhitch our gazes from the mesmerizing sight of so much water unleashed with a fury and power beyond the ken of our understanding, belittling the significance of our puny human presence.

And yet, frozen in a timeless moment, we melded into the eternal scene, enveloped in seething spray and blinded by the wild magnificence of it all.

John Olmsted, in his 1868 classic, A Trip to California, poetically captured the sensation that we experienced that morning at the base of the waterfall which the Ahwahneechee called Cholock:

“ . . . filling our eyes and ears, the wind roaring, and bellowing, and lashing against us, and the thunders of the cataract booming on our ears – surely this was a position to be sought but once in a lifetime . . .”

So fearful were the Yosemite people of this unleashed power, they invented stories of witch spirits inhabiting the pool, called Poloti, who sought vengeance and punishment (in their myths) for daring to trespass on their territory. Why did nature frighten them so?

We returned the way we came, by now the sun climbing high and warming things up and noted many more people out and about on the trail. Let the parade of humanity begin. We got back in the car for the short drive to the store, where we stocked up on some munchies to fortify us on our all-day outing. We then caught a shuttle bus to the trailhead at Happy Isles (no cars allowed).

By the time we got to the Curry Village stop, the bus was jammed full of tourists from all over the world, and at the next stop, a group of a dozen young children boarded with their adult guardians, marching in dutiful unison to the back of the bus where they stood erect like packed in sardines.

The tone was set for the remainder of the day – all these people were going to the same place as I had chosen to take Javier. Of course, I had decided on the absolute most scenic and accessible hike in the park – the John Muir Trail out of Happy Isles, to the two spectacular falls of Vernal and Nevada, with unmatched back country scenery. The fit and hardy, though, would leave the hoi polloi far behind, and continue on to Half Dome.

And if time merited and you had energy to spare and perfectly functioning body parts, beyond to Tuolumne Meadows, and then, if you were really ambitious, and could kiss your job goodbye for several weeks, and had the stamina and intestinal fortitude and athletic endurance and didn't mind dealing with bears and rattlesnakes and mosquitoes, you could hike the John Muir all the way to the top of Mount Whitney, some 200 miles down the trail.

Still, what a dispiriting parade of mainstream humanity! Yammering kids on school field trips. Amateur photographers lugging tons of equipment. Buddy hiking groups. Naturalist led outings of fifteen or twenty wildflower nuts and bird-loving enthusiasts.

Dozens of family units. Lots of Japanese, Chinese, Germans, French. It hit home why it's been twenty-six years since I've been back. I really do despise crowds, any and everywhere, even where they’re expected, like rock concerts and sporting events, but in nature, when too many people are swarming around, one on top of the other, causing foot traffic jams on the trails – or, as in the case of Half Dome – lined up for hours waiting their turn – aaargh.

Just before his death in 2000, David Brower opined – lashed out, really:

"Congestion problems are relatively easy to solve; as Ansel Adams said, 'When the theater's full, they don't sell lap-space.' National parks were created to be a natural haven from the world of mindless development and endless growth. Placing no limit on the number of current visitors who can visit the park at one time is a violation of the Organic Act and a breach of our contract with future generations."

Ten years later, Master Management Plan or no, they're still packin' 'em in at Yosemite more than any other park in the nation. And yet, contradictorily, here we were, part of the crowd, too, just one of the masses, no better or worse than anyone else. So, for one day out of ten thousand, if I can’t beat 'em, I think I'll join 'em, without further ado or complaint, I promise.

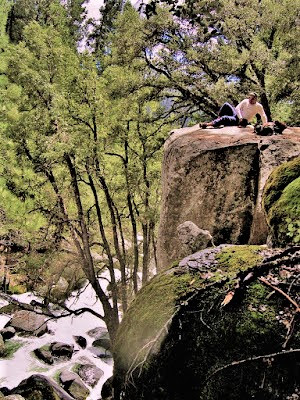

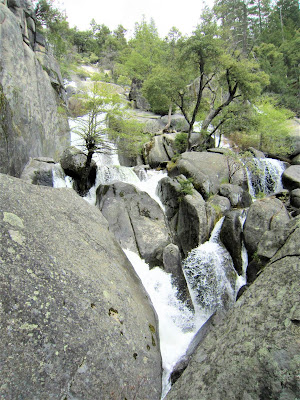

One after another, during the first eight-tenths of a mile – all uphill – the paved trail was packed with people, all determined to make the trek to the bridge. The first leg took us high above the roiling Merced, through a boulder-clogged, mossy oak forest, past a teasing view of 370 ft. Illilouette Fall, hidden high away in a nearly inaccessible canyon.

We finally got to Vernal Fall bridge, a stopping point for ninety percent of the people, and last chance to fill water bottles and relieve yourself in the comfort of an indoor toilet. The remaining ten percent who continue on – still a large number of people, probably around 200 in the next few hours alone – must be ready for a grueling mile and a half hike and several hundred feet of switch backing elevation gain to attain the top of Vernal Fall.

It sure seemed a lot farther than a mere couple of miles all told, and yet so many of these seemingly out-of-shape people, little kids, teenage girls and boys, older men and women, even folks I deemed obese, took it on in sporting fashion, seemingly none worse the wear, unlike poor Javier and I who ended the hike limping back like two old worn-out bear scouts.

The view outward, for lack of more descriptive flourish, blew our minds. The shiny white pate of monstrous Half Dome – known by the Yosemites as Tis sa ack, the cleft rock – rose in our purlieus to over 4000 ft. above the valley floor attaining rarefied heights of 8836 ft.

Climbing up its slick contour, in line with many others (but nothing like today's circus), as though on pilgrimage, attaining the summit and trembling with excitement at the accomplishment, overcoming my fear of heights, and then the jaw-dropping vision unfolding before me of the boundless expanse of valley 4000 ft. below.

Just dizzying, purely exhilarating. And to think, some poor souls have met their death here (on average twelve people die each year in Yosemite National Park) – slipping on cable route, suffering heart attacks on the climb up, getting struck by lightning, bungled base jumps, climbing mishaps, and a suicide or three.

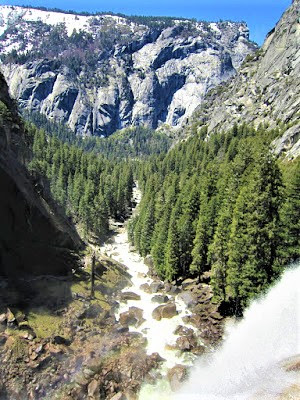

All around, dominant views of other imposing monuments prevailed – Tis sa ack’s sister domes, Mount Broderick (6706 ft.) and the humbling vision of Liberty Cap, jutting skyward in our immediate space soaring to heaven-bound realms of 7076 ft. – three gigantic geologic obtrusions forming a towering vista of raw, rugged rock, a panorama of mountainous bliss that left us speechless in wonder and amazement.

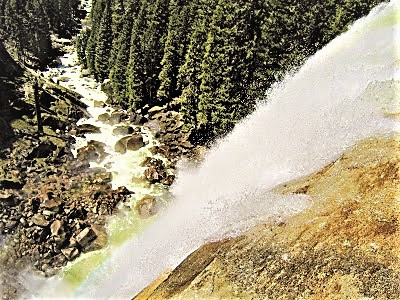

Our vantage point at Vernal Fall afforded eye candy views of a 300+ ft. drop of forcefully plummeting white water. We were looking down on it from atop, since the famed Mist Trail, a shortcut to Half Dome, lay far below, and was closed off – although a ranger told us later in the day that, despite the closed gate and sign – it had just been opened.

That would have been a much different viewing angle from below, and would have required wet weather gear, but where we were, high above the falls:

Why, it was pure magic!

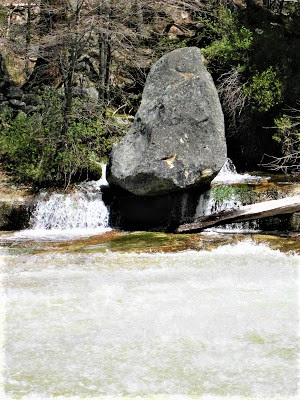

Taking it all in for a long time, we next made our way down another half mile to the second bridge crossing and spent some time exploring up and down the cascaded stretch of river just upstream from where it pours into the Emerald Pool.

From there, the Park Service has built an overlook, and by the time we got there, it was overrun with dozens of picnicking people whom we had seen pass by high up when we were eating lunch off the trail. I had lost track of counting the passers-by, but there were at least 75 people down there now eating, milling and horsing around, enjoying a picture perfect 75-degree blue sky day.

Who am I to wish they weren't here?

We milled about and mingled a bit with the crowd, spending a few minutes taking photos and leisurely absorbing the magic scenery, and then returned the way we came, seeking retreat back up to the lonelier stretches above the Emerald Pool. It amazed me how easy it was, after all, to escape the hordes.

For some reason, the ovine masses seem more comfortable sticking together in big groups. Maybe it's a safety thing? Also, most puzzling, nearly everyone was hiking in this sun-blasted wilderness without a hat, and some in flip-flops and other flimsy footwear! (Must be nice bein’ twenty-something; been so long I can’t remember!)

Finally, it was time to head back. The reverse course seemed about twice as far and three times as tough – don't let anyone tell you downhill is easier than hiking uphill; it ain't! Each step of the way pulverized my feet and buckled my knees.

We congratulated each other on our accomplishment, which from some other younger or fitter person's perspective, might seem, well, like just a walk in the park. But for us, it was more than three rugged rock-strewn miles and upwards of two thousand total feet of hard gained and lost elevation, and for a couple of old grizzly bears, that ain't a bad day's work(out).

But how would we ever get to Half Dome, or for that matter, to the top of Mount Whitney if this little ol' day outing kicked our ever-lovin' butts?

I felt a little like Muir did, that Yosemite was my “university of the wilderness” and this day, although not quite Muir’s six-yearlong graduate course, was my own little one-day workshop in the tenets and principles of natural history.

Not surprisingly, Yosemite's blessing and curse is its fantastic scenery and mind-blowing wonders of nature.

It is these falls, the eternal draw of powerful water, that attract crowds seeking spiritual experiences. And when the water diminishes or disappears altogether, bold, bare rock – Mother Earth's bleached bones exposed – remains to challenge our concept of power and eternity.

These displays of geology, left for us to ponder by the ice-sculpting forces of glaciation, weathering and erosion and natural processes of exfoliation, reach their most sublime in the notably glorious rise of granite called Tote-ack-ah-noo-lah.

.jpg)

Expert rock climbers, intent on defying death, come from around the world to climb the rock of ages, while the rest of us can only sit back and contemplate its massive size, and wonder about, without much hope for resolution, its creation, purpose and existence.

Gazing up in mindful serenity at the largest exposed granite monolith in the world, seated beside the river, or reposed in the garden meadow under a spreading oak tree, we are unable to deny the visceral power it holds over our imagination.

Unable to overcome the illimitable spell it casts over our lives, as we try to come to terms with our utter insignificance and looming mortality in the face of such an imponderable natural wonder.

Gambolin' Man highly recommends devoting a half hour to watching these three park service videos as a complement to this post.