CHACO CULTURE NATIONAL HISTORIC PARK: Mystery & Prehistory, Ancient Culture Flourishes in Desert Wilderness Setting

.JPG)

We're seeking to commune with the spirits and immerse ourselves in the vibrational energies of a mystical desert. We're hoping to tease out titillating secrets of a long-vanquished place held in great reverence to this day. A remote place of enduring mystery lost to time in a desolate, arid world buffeted against tall red rock cliffs and endless land and sky.

An ancient sacred place called Chaco Canyon.

.JPG)

Our final approach takes us precariously across 16 miles of bare, hardscrabble surface that could transform in a few terrifying minutes into an unexpected flash flood of pummeling projectiles of tree trunks, refrigerator-size boulders, frothing mud, and raging water.

|

| Public domain |

Our bumpety-bump ride finally brings us to the marquee destination in Chaco Canyon – a once great and powerful ceremonial center known today as Chaco Culture National Historic Park, of such outstanding prominence that it is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Chaco Canyon's ancient realm encompassed an area of nearly 30,000 square miles, about the size of Ireland. Resting at an elevation of 6200 feet above sea level, the exposed desert plays havoc with unpredictable and extreme weather. It is bitterly cold in winter, brutally hot in summer, and subject to severe year-round aridity, with less annual precipitation than the Saharan country of Chad.

Public domain

Public domainIt was in this "unlikely" setting, like the ancient Maya's "unlikely" florescence in sweltering "impenetrable" jungle settings a world away, that a sophisticated "Chacoan" civilization took root and built remarkable architectural wonders, laid down a complex matrix of engineered earthworks and road systems, and lorded over their realm for 300 years.

Known as Ancestral Pueblo (or Puebloan), the builders of Chaco Canyon live on in the hearts and minds of present-day Pueblo Peoples of the Four Corners area: Hopi, Acoma, Zia, Laguna, Keresan, Tanoan, Cochiti, San Felipe, Santo Domingo, Navajo, and others.

.JPG)

Hopi descendants bestow the name "Hisatsinom" on their ancestors, meaning "People of Long Ago" or the "Ancient Ones." Others continue to use the descriptor "Anasazi," from the Navajo word "Anaasází," literally meaning "Ancient Enemy." Most Pueblo Peoples, however, consider "Anasazi" to be derogatory and prefer to avoid using a term that perhaps is a painful reminder of an unfortunate period or episode in their past.

Given the repugnance associated with "Anaasází," whoever the "Ancient Enemies" were (Toltec invaders? Outlier warrior tribes?), they must have exerted an outsized, negative influence precipitating the social dissonance, violence and terror which is presumed to have played a key role in the breakdown of Ancestral Puebloan high culture in the 12th and 13th centuries.

.JPG)

Since the end of the last Ice Age, these harsh, arid, fragile, spectacularly beautiful canyonlands, mesas and desert washes provided Archaic Period hunter-gatherers resources and shelter needed to thrive and survive for millennia in synch and harmony with the cycles of seasons.

|

| The Great House of Pueblo Bonito, reconstructed (Public domain) |

_2007.jpg)

Public domain

Vexing questions flash flood through our minds: how were inhabitants of this land able to scratch out a living? Was the climate wetter, more propitious many thousands of years ago? How did simple hunter-gatherer / agrarian tribes manage to swell in numbers and grow their settlements and communities to support up to 50,000 inhabitants? How could such an inhospitable desert environment give rise to a civilization of high culture, art and wide-spread influence over 1000 years ago? And what became of it?

Three-hundred years might not seem like a long time for a civilization's heyday, but given numerous impediments and limitations – water scarcity, animal game fluctuations, poor soil conditions, natural resource depletion, overpopulation, unpredictable weather patterns, navigational difficulties, hostile invaders, and sporadic internecine or outsider warfare – perhaps a timeframe of 300 years of sustaining one of the world's great ancient cultures should be considered an extraordinary achievement, not a flash in the pan anomaly.

The complexity of social life is on full display at Chaco Canyon, evidenced by impressive architectural achievements comprising over 12 Great Houses and 4 Kivas spread over 9 miles along the canyon wall; an estimated 400 settlements supporting a population in the several thousands; trade with littoral peoples from Mesoamerica; a 400-mile network of engineered roadways and earthworks; and other clues such as their ability to grow and store food (corn).

.JPG)

Note: New evidence suggests the inhabitants of Chaco Canyon had to import their corn from a site 50 miles distant because conditions were not suitable for large-scale agricultural production.

.jpg)

There is little doubt about Chaco Canyon’s juggernaut status and indisputable clout as a cultural, economic, ceremonial and administrative powerhouse of the prehistoric American Southwest.

.jpg)

Interestingly, archaeological evidence has uncovered in the greatest of the Great Houses, Pueblo Bonito, generational remains of elite matrilineal succession; a society of a single lineage traced through the female line for 330 years whose influence and power spread out over a great arc throughout the San Juan Basin.

.jpg) |

| Public domain |

The fact that matrilineal descent is common among contemporary Pueblo Peoples suggests that this practice – dominant matriarchal power – was probably in existence among Ancestral Puebloans, though scholars are uncertain and in disagreement over whether it was just at Chaco Canyon that women ruled the roost, or was it more widespread among prehistoric cultures of the Four Corners area.

.jpg)

Foreign presence is clearly evident at Chaco Canyon. Various architectural stylizations and trade items associated with Mesoamerican culture have been found in excavations along with human remains in tomb settings: prized items such as scarlet macaw skeletons, jade, turquoise, copper bells, seashells, and cacao.

|

| Public domain |

Randall H. McGuire, an anthropologist from the University of Arizona, established in a paper in 1980 ("The Mesoamerican Connection in the Southwest") that:

.JPG)

" . . . connections between Mesoamerica and the Southwest cannot be denied and that many traits encountered in the Southwest are derived directly or indirectly from Mesoamerica."

|

| Public domain |

Ample troves of evidence throughout the ancient Americas, and the world, support the premise that prehistoric societies depended on trade for prosperous development and relations. Establishing and controlling long-distance trade networks in existence for millennia enabled societies to exert economic influence and control. Ancient trade routes functioned as an efficient means to traffic goods and unite disparate peoples who shared cultural values and similar cosmological-spiritual-religious traditions.

|

| Public domain |

High ranking politicos and powerbrokers valued exotic trade items for their luxury and elite connotations, while shamans, priests and hierophants prized them for their mystical, ceremonial and power enhancing purposes. All of which no doubt helped fuel Chaco Canyon's growth and development into a mighty ritual and ceremonial center.

Over a period of three centuries, generations of Ancestral Puebloans built their massive circular structures known as Kivas and erected their monumental Great House complexes comprised of dozens of apartment building-like structures seemingly reserved for elite rulers.

Constructed with thousands of precisely cut three-foot thick sandstone blocks and incorporating over 200,000 spruce, pine and fir trees that were laboriously harvested and hauled from high elevations sites 75 miles distant and then precisely chiseled to fit as rooftops and support beams, Chaco Canyon's impressive buildings, some rising over 5 stories, could be spotted from miles away.

Many seem enclosed, blocked off, unlived-in, as though serving more of a ritual or ceremonial purpose beyond our ken than actual living quarters for the hoi polloi. Pueblo Peoples say that Chaco Canyon was a special gathering place where tribes and clans converged "to share their ceremonies, traditions, and knowledge" (NPS website), but did the common people actually reside in these structures? Does evidence suggest otherwise? The Great Houses and Kivas remain an enduring mystery as to their ultimate purpose.

The imagination strains visualizing the enormous effort and social control required to organize and manage a labor force of such magnitude to pull off multiple massive public works projects: the building of Great Houses and Kivas, while concomitantly laying down an elaborate system of 27-feet wide roadways across hard dirt surfaces and engineering complex earthworks such as dams, levees, irrigation canals, water catchments and blufftop reservoirs to ensure and protect precious water runoff and supplies. Sure, the work was ongoing over 300 years, but still!

.JPG)

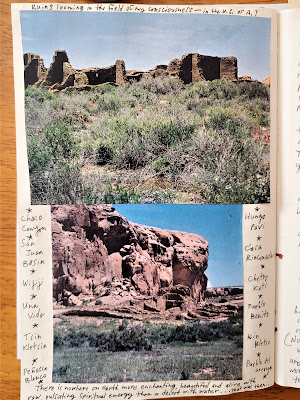

Pueblo Bonito, Una Vida, and Penasco Blanco were the first of the Great Houses to be erected. They were followed 150 to 200 years later by smaller houses – Chetro Ketl, Hungo Pavi, Pueblo Alto, Pueblo del Arroyo, Kin Kletso, Casa Rinconada. Still others, such as Tsin Kletsin, Wijiji, and Kin Bineola, and probably dozens of other outlying structures, have crumbled to dust and are lost to time. But not to spiritual memory and a visceral connection held by contemporary Pueblo Peoples.

.JPG)

.jpg)

A controversial view espoused by maverick researcher and explorer Richard D. Fisher promotes the idea that the Kivas were nothing more, nothing less than . . . grain silos used for storing corn! Fisher might be on to something, but as with all fiercely protected academic paradigms and canonized scholarly narratives, 99.9% of archaeologists no doubt disagree vehemently with his analysis and history-upsetting conclusions.

(See CHACO MYSTERIES SOLVED?)

.JPG)

I'm willing to entertain his hypothesis, which is largely based on research conducted at large-scale granaries discovered at the ancient site of Paquime Sky Island in Mexico. Deducing from this, Fisher challenges widely-accepted doctrine, proposing instead that Ancestral Puebloans built:

.jpg)

“ . . . distinctively large impressive buildings whose primary purpose was for the long term storage of vast quantities of corn . . . I suggest that with their surplus corn growing capacity, they developed large religious ceremonies atop the platform mounds . . . These ceremonies attracted the clans from across the Chaco great house system . . . What I am striving to explain is how a fundamentally practical system of managing the food supply in Chaco Canyon and elsewhere translates into a sacred life-style and cultural legacy that endures to this day.”

.jpg)

I remember as a boy my Mom gave me a book on Pueblo Bonito that fascinated me to no end with its idyllic depiction of a peaceful way of life, an idealized, glorified existence in harmony with the natural rhythms and cosmic cycles that governed Ancestral Puebloan ritual-focused relationships to the Earth and Sky and to the passing and changing of seasons.

And how dumbstruck I was at 11 years old when I got to the chapter on their "sudden" disappearance in the century between 1090 and 1180 A.D. What caused a calamitous breakdown of social structure? What conditions led to a "sudden" demise?

|

| Public domain |

We know from tree ring analysis, that 1200 years ago the Southwest experienced what in various native tongues is known as The Big Drought, The Empty Cloud, The Dry Death. (And we also know today the same area is experiencing its most severe Dry Death since that time.)

.jpg)

Drought and its cascading effects – deforestation, erosion, disappearance of game, and inability to grow crops – certainly played an outsized role in the demise of Chaco Canyon's great reign. Paleoclimatic data reveal a major stoppage of rain during a 50-year period beginning in 1130 A.D., resulting in chronic climate instability and severe environmental stress, all of which contributed to social unrest and upheaval, foreshadowing the catastrophic collapse of Ancestral Puebloan culture at Chaco Canyon and beyond.

.JPG)

I ached with a yearning adolescent fury to understand what happened at Chaco Canyon. Where, Mom, did everyone go? Why were they forced to leave? Please explain to me how a great civilization and its entire people could simply vanish? Or was it so "simply" and did they really "vanish"? I couldn’t get my little 11 year old brain around the concept.

.jpg)

Years later, as a student of anthropology, I learned more about ancient civilizations of Mesoamerican (and elsewhere) that rose and fell with regularity as successive cultures (victors? squatters?) literally building on the foundational ruins of the vanquished. I learned that Great Demises are a common theme that tie all ancient high cultural traditions together in a fate of ultimate disintegration after a "classic" or golden period of high achievements in the "4 As" – Agriculture, Architecture, Art, Astronomy. (Lessons in store for us?)

By 1132 A.D., the last of the Great House and Kiva construction took place, and gradually (not quite overnight), Chaco Canyon was abandoned as the people scattered and fled in response to centralized authority dissolving in some unknown crisis, some natural calamity or wide-scale fracturing of the social fabric.

.jpg)

Or all of the above. Ultimately, nature's whims and social anomie create untenable scenarios for the continued status quo; drought and environmental degradation induces societal stress leading to a breakdown in norms and behavior; starvation, warfare and violence result; people flee to outlying areas to "shelter in place" then emerge, regroup, and cycles of life continue.

Another consideration, hotly debated by scholars, is the presence of conquering "enemies" who invaded and brought with them frightening powers of assimilation, violence and warfare, along with an evil tradition: cannibalism.

Analyzed bone fragments and dismembered bodies found at many sites throughout the Four Corners and, specifically, at two sites at Chaco Canyon, offer forensically indisputable, but incomplete and highly contextualized evidence of anthropophagic indulgence. Whether the short-lived anomalous eating of human beings involved ritual sacraments, or was employed as a terroristic means of control, or was a necessity to stave off hunger (most unlikely), remains to be seen.

.JPG)

One writer, Mark A. Carpenter, disputes the "drought collapse theory" based on fire scarring, ritualized murder, and a highly stratified, elite and increasingly paranoid society. He opines in Ancient Origins Online:

"Imagine people at the time, not having enough food to eat, water to drink, and on top of these hardships, being commanded to participate in building projects while their loved ones were abducted, butchered, and devoured. It is not difficult to imagine that, after generations of hardship and suffering, these oppressed classes at Chaco Canyon violently revolted against their cult leader overlords, dismantled their sacred spaces, and set fire to the great kiva, never to return."

.JPG)

Such accounts may be fanciful and lacking in hard evidence, but, whatever happened, it was hugely disruptive and begs the question: where did all the people go? It must have been a repeat scenario similar to the mysterious abandonment of their jungle citadels and "sudden disappearance" of the ancient Maya a few centuries prior.

Ancestral Puebloans probably fled to outlying areas in a mass diaspora, abruptly leaving everything behind, or taking what they could, assimilating with other tribes, reordering their lives in accordance with the timeless cycles of transhumance, of simpler existence. The glory days were over for good and hindsight tells us that even more horrible events and fate awaited in the centuries ahead.

Recent scientific discoveries continue to bear fruit in helping us piece together and understand the past – and hopefully learn from – specifically the drivers that cause thriving civilizations to implode and decline: anthropogenic assaults on Mother Nature. In October 2021, a multi-disciplinary team of researchers from the University of Cincinnati published their results in "Ecosystem impacts by the Ancestral Puebloans of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, USA."

|

| Public domain |

The researchers established that as early as 600 A.D. Ancestral Puebloans had begun degrading their environment by over harvesting the woodlands for various purposes (timber, nuts, fuel). Because trees are the key sustaining element holding soil together, they determined that the decline in tree density led to a domino effect of deleterious environmental breakdown – irreversible habitat degradation, in other words.

" . . . unsustainable land-use practices resulted in woodland tree removal and bouts of erosion that had the effect of reducing the resilience of the landscape and likely exacerbated the ability of the Ancestral Puebloans to endure a period of extreme aridity . . . this circumstance forced the inhabitants to range widely for essential resources, especially fuel and game. These stressors, combined with drought conditions, likely contributed to the departure of the ancient occupants from the canyon."

“A tree is beautiful, but what’s more, it has a right to life; like water, the sun and the stars, it is essential. Life on earth is inconceivable without trees. Forests create climate, climate influences peoples’ character, and so on and so forth. There can be neither civilization nor happiness if forests crash down under the axe, if the climate is harsh and severe, if people are also harsh and severe . . . what a terrible future!”

.jpg)

We spend most of a full day exploring Chaco Canyon's main dwellings, reading about details of the site in park brochures and a guidebook, engaging our minds in fanciful reconstructions and imaginings of how things must have looked, and passing many idle moments in the shade of megalithic boulders fallen to the desert floor from high cliffs pondering the stark, peaceful beauty of the desert surroundings.

.JPG)

With the day warming up after making the rounds at Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl, we pack a lunch, ensure our water provisions, and set off under a blazing sun mercilessly bearing down on us for a 4-mile hike along Petroglyph Trail.

.JPG)

.JPG)

We hope to have the energy to continue our sunbaked trudge along the sandy basin floor to an alluring destination at trail’s end – Penasco Blanco where a crescent moon and painted sunburst adorns a rock, believed to represent the Crab Nebula supernova explosion witnessed by ancient stargazers in 1054. A handprint above seems to announce, "I am here. I am witness to something magical and imponderable."

.jpg) Photo courtesy of Alex Marentes ("Buggs" on Flickr)

Photo courtesy of Alex Marentes ("Buggs" on Flickr)We are eager to make it there. But after a small lunch break in a tiny nook of shade provided by a boulder, with the sun beating down relentlessly, me in shirt-sleeves, no sunscreen and nursing a bum ankle, and Gambolin’ Gal not exactly up for it either, we wisely conclude it would be hubris of the highest order to add several extra miles and intense sun exposure to make the pilgrimage "just" to say we saw the starburst panel.

|

| Crab Nebula explosion (Public domain) |

Besides, we’re short on – the thing Chaco Canyon has always been short on – water. We turn around and call it a day in the back country, disappointed not to have laid eyes on the famous pictograph memorialized on a protected rock face by the unknown artist. A big shucks, dang it, and oh well – next time!

.JPG)

We check out Casa Rinconada on the way back. Built in a style more typical of a village community than the grand public ceremonial buildings of Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl, the "Casa" is a short walk to the site of the largest Kiva built at Chaco Canyon, and one of the grandest in all the Southwest.

The subterranean sacred circle measures 8 to 10 feet deep with an inside diameter of 60 feet, complete with ventilation shafts, smoke pits, reliquary niches, and seating benches to hold up to 100 people.

.jpg)

We imagine a scene of over 100 people intimately engaged in sacred ceremony, offering up ritual propitiations to the Corn Goddess, the Rain Deity, to the protective spirits of Mother Earth, and to, perhaps, a mysteriously worshipped Scarlet Macaw Sun God cult. And then we are slightly deflated by Fisher's heretical theory that reduces Kivas to mundane purposes, i.e., they were not designed to be ceremonious or ritual in purpose, rather, he contends, they were simply:

“ . . . corn silos, as might be expected to be found in a culture whose entire purpose and focus was on growing corn.”

Whether church or corn silo, some kind of high sacrament was associated with a culture whose entire lifeway – like that of ancient Mesoamerican civilizations – was centered on corn. And not just corn, but the "Holy Trinity" of their sustaining crops: corn, beans and squash.

|

| Ceremonial corn patch, Fremont Indian State Park, Utah |

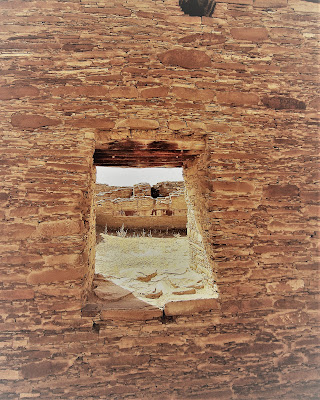

Walking around this gigantic Kiva, we come to a window frame, through which the designers ensured that a shaft of light would shine through on the morning of the Summer Solstice.

.jpg)

This level of astonishing skill, the ability to understand science, and the technical capability needed to carry it out, i.e., align structures on Earth to coincide with the predictable motion of celestial objects, was perhaps an introduced technology from more advanced cultures in Mesoamerica or beyond. Or, did such superior technical prowess, highly advanced astronomical knowledge and geodetic skills arise independently in so many of the world's prehistoric cultures?

We see this notably at the oldest recognized archaeological site in the world of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, dating from at least 10,000 years ago. It is plainly observed at the Ggantija Megalithic Temples found in Malta; famously at the pyramid sites in Egypt and at Chichen Itza's famed El Castillo / Quetzalcoatl alignments in Mexico; at the amazing Serpent Mound in Ohio (whose massive jaws orient to swallow up the setting sun on the Solstice); and at the intriguing Poverty Point complex in Louisiana. These and many more examples from around the world are compelling evidence of a diffusion of knowledge (although this view is not shared, in fact is anathema, to many defenders of canonized archaeological faith.)

Why did the Ancient Ones go to such lengths? Phillip Tuwaletstiwa, a Hopi geodesist and scholarly keeper of oral history, tradition and creation stories, has noted (referring to Ancestral Puebloans of Chaco Canyon):

"If there was a way to transfer the orderly nature of the cosmos down onto what seems to be chaos that exists here, then you begin to then integrate at this place both heaven and earth. And this would be . . . the center place."

Gazing beyond to the lonesome mesas, the ceremonial centers appearing in the distance as Lilliputian ruins, a grander vista opens, an azure desert sky stretching far and wide, dappled with fluffy clouds spreading to infinity's low horizon.

.jpg)

Contemporary Pueblo Peoples believe that this energy is not vanquished, but omnipresent, vibrant, part and parcel of their religious heritage and cosmological belief systems. Tuwaletstiwa has spoken the words:

“We don’t like that word, abandoned, we don’t think in terms of the time between events. We have migrated many times. We didn’t vanish. We were many places before Mesa Verde, and many places after. I visited the veterans’ cemeteries in Normandy, and I treated them with respect and gratitude. In Chaco and Mesa Verde, those are my ancestral people. I need to treat them with respect as well. To us, these are living, breathing places.”

.jpg)

With dusk approaching, we make arrangements to spend the night at the official campground. There is no dispersed camping within an 80-mile radius. So we throw our ground covers down on the red dirt and sit at a picnic table watching reverently as the sun slowly sets over the looming red canyon wall sheltering a dozen or more RVs and a sea of colorful tents in an amusement park like atmosphere of bubbly tourists, noisy kids and all manner of obnoxious contraptions contributing to a demoralizing sense of . . . not exactly an unforgettable outdoor wilderness experience.

.JPG)

All so typical of – and why I always try to avoid! – mainstream Americana campgrounds due their obnoxious assaults on peace and quiet: smoky campfires and grills befouling pristine air; out of place discordant music; parents shouting at unruly kids; impossible to ignore loud, dumb chit-chat; and all the harmony-shattering gizmos and gadgets involved in "camping, mainstream American style" – loud pumps for air mattresses and louder generators to charge up RVs.

Chaco Canyon is a designated 99% Dark Sky Zone, one of precious few places remaining the country where we have the opportunity to view the heavens as our ancestors did – in all its pristine naked glory – when to gaze up was to succumb to awe and wonder at the magic and mystery of creation. And here people don't have the good, decent, common sense to shut up and turn off their lights! (This campground must be the remaining 1% of the World Heritage Site where artificial lighting is allowed.)

Why does it have to be like this, people?

.jpg) Photo by K. Alden Peterson (NPS)

Photo by K. Alden Peterson (NPS)Set up near us, a neighboring tentful of wacky women are well on their way to obnoxious inebriation. One says to me, "What?! No tent?!"

"Yep, that's right. No tent. We came to sleep under the stars, not enclose ourselves in a polyurethane bubble. How else would we be able to see the night sky and all the beautiful stars?"

.jpg)

The woman gives me a strange, clueless look. Eventually, thankfully, things settle down and the grand show unfolds, a surreal, magnificent sight to behold with a sparkling Milky Way illuminated in a spectacular arch across the sky. Shooting stars occasionally streak in brilliance, then fizzle out in the firmament's inky vastness of space. Clusters of sparkly pinpoints of stars bedazzle and hypnotize us with dreamy thoughts of entropy, of infinity and eternity, of how it all begin and when it will all end. If never, or forever.

|

| Pillars of Creation (Public domain) |

Questions and mysteries the Ancient Ones no doubt pondered as well.

How lucky there is no moon tonight! We're able to see light-years into the – past! We're also able to trace the movements of orbiting satellites launched into space by the hundreds these days. The price we pay for our modern technological obsessions with the internet, mobile phones, navigation and GPS systems we are so heavily reliant on that we've – uh, lost our way. Only a fraction of the 2,666 operational satellites are for imaging of land and sea features to help map and support studies of the Earth.

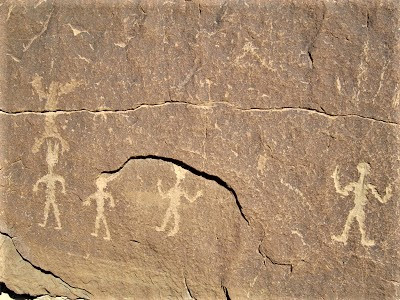

In the morning, we stop in the Visitor Center to browse, and chit-chat with a Park Ranger of Puebloan heritage. Her thick black hair is braided and drapes nearly to the ground. Skimming a book, I find a stunning petroglyph photo that I had not seen at Chaco Canyon. The Ranger informs me it and the others I'm marveling at are all off-limits to the public, sorry. They're by far the most decorative and expressive of the rock art symbology at Chaco Canyon.

.JPG)

I am chagrined. The Ranger is sympathetic. Oh, well, we've seen a lot, and can't expect to see everything. On our way out, we pull to the side of the road to admire a stand-out geological feature, the 400 ft. tall Fajada Butte, rising to over 6600 ft. above the desert floor. The sentinel is a spiritual monument, a sacred island in the sky.

.jpg)

Atop this marvel of geology, the Ancient Ones constructed sophisticated Solstice and Equinox markers, but trampling hordes of clumsy and disrespectful visitors disturbed the site ("foot traffic") by dislodging one of the slabs, so it is now off-limits like the petroglyph panel in the book. We can only appreciate it from afar and imagine the elaborate precision, the ingenious feat of mechanical wizardry and astronomical knowledge that it took for the designers / builders to create the sophisticated calendrical system.

|

| Public domain |

The Ancient Ones employed three large flat rocks to track the Solstices and Equinoxes in an 18.6 year cycle of the moon. As the declination of the sun increases or decreases during its passage across the sky over the course of the year, a "sun dagger" (ray of light) aligns to slice directly through to the center point of the large spiral petroglyph carved into the rock facade hidden behind the rock slabs. (To learn more, these videos are worth checking out: Solstice Project.)

(Paul Charbonneau, High Altitude Observatory, National Center for Atmospheric Research)

.JPG)

Tuwaletstiwa, the Hopi geodesist, has said:

"There were very precise ways of tracking the sun. The job fell to a man our people called the Sun-Watcher, who observed the solar journey."

.JPG)

As we are fully aware by now, Ancestral Puebloans, like many high ancient cultures the world over, were keen observers of the night sky and understood complex relationships of celestial movements and objects to Earth and they incorporated stunningly precise alignments and sacred geometries into their constructions marking such phenomena as a way to accomplish – what, exactly?

.JPG)

Why were the Ancestral Puebloans (and other ancient sky observing societies) so obsessed with capturing precise cycles of the sun, moon, stars and planets? To record and measure time? Impress the populace? Pay homage to the Gods? All of the above, no doubt.

Public domain

Ultimately, demonstrating a manifest connection to the heavens, to the Gods, through a "mystical" understanding of the world by means of manipulating extraterrestrial lunar cycles and solar rhythms endowed hierophants and spiritual technicians with keen and unique abilities – supernatural powers – to control and manipulate in God-like fashion a superstitious populous rendered awestruck and in utter adulation and amazement at such feats.

Imagine being able to wield supernal powers, knowing when and how to synchronously coordinate planting and harvesting times with the orientations of phenomenological events and astronomical observations. In ancient (and modern) times, priestly power, the world over, has always hinged on an ability to bamboozle the masses and convince them of their entheogenic ("the divine within") power.

Who really knows why they went to such great lengths to understand the relationship of the sun, moon and stars and other celestial events and movements to their buildings and earthworks. We think we know it was because of all the above enumerated reasons involving ritual invocations, propitiation to the Gods, and priestly power moves.

But perhaps above and beyond commemorating the "Center Place", the Ancient Ones were motivated by something else. A driving obsession that spurs our own knowledge-for-knowledge's sake thirst and quest for answers: scientific endeavor, pure intellectual curiosity, and a deep species need or instinct for phenomenological inquiry into the nature and meaning of the universe, self, and humanity's place in it.

.JPG)

Driving out of Chaco Canyon, we leave behind the mystery of the Great Houses, the Kivas, the many dwellings on which the Southwest’s most sophisticated cultural center was built and sustained.

It's difficult relating to our present circumstances, driving away in a big SUV, our reliance on an oil-based, carbon-burning economy, caught up in a modern world of overpopulation, crime, war, strife, poverty, hunger . . . and yet, a lot of our present-day dysfunction is nothing new, I don't suppose.

What important lesson(s) can we learn from the Ancient Ones?

Perhaps the stinging rebuke that we are our own worst Enemy . . .

Humans have always been prone to war, subject to famine, prey to desacralizing practices leading to erosion, deforestation, soil infertility, and resource depletion – all of which have been proposed as causes for the downfall and abandonment of Ancestral Puebloan culture at Chaco Canyon.

.JPG)

– wherein the Venusian reptile scientists base their entire theory of reconstruction and understanding of a mysterious race of extinct humans from 21st century planet Earth on a small metal box they dig up containing a treasure-trove discovery of an ancient reel of film.

.jpg)

.JPG)

" . . . all this labour, all this research, would be utterly in vain . . . millions of times in the ages to come . . . those last few words would flash across the screen, and none could ever guess their meaning: A Walt Disney Production."

.jpg)

The descendants of Ancestral Puebloans carry on in the Four Corners area as a culturally-related, united, vibrant people, in possession of hoary legends and sacred myths, shared remembrances, and a collective consciousness of the ancient days, the old ways.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home