BIG BREAK REGIONAL SHORELINE: Paddling the Wind-Swept "Inland Coast" of the Great California Delta

A great blue expanse beckons from beyond the shallow trough of water gently lapping at your old-school Radisson docked at Big Break Regional Shoreline's alluring put-in.

What better place to sweat out an adventure, rekindle awe, and stoke curiosity than in these 1648 acres of brackish tidal and freshwater marshes, sloughs, ponds, creeks, alkali grasslands and meadows.

Big Break essentially is a rehabilitated parcel of once-industrialized, long-neglected land in the much-abused California Delta, not all bad news. Today, park stewards have created a model for much-needed shoreline reclamation efforts.

Unlimited recreational possibilities galore in a big water zone situated in the Pacific Coast's largest estuarine ecosystem created by the merger of the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers, two of California's great arteries that drain half of the state's watershed.

But decades of man-made manipulation have degraded and transformed the pristine estuarine ecosystem, today characterized by the EPA as having been replaced by:

But decades of man-made manipulation have degraded and transformed the pristine estuarine ecosystem, today characterized by the EPA as having been replaced by:

" . . . sub-sea level, levee-protected islands and simplified, deep, wide, armored waterways."

Still, with a little help from human friends, the resiliency and adaptability of life is on remarkable display at Big Break, a place of profound beauty, where (forgive the EPA's prosaic description) natural rhythms and processes occur in a world-class marine / riparian environment.

It looks amazingly like ancient Egyptian tidal sloughs (third largest in the Delta), labyrinthine estuary channels, and tributary outlets draining Mount Diablo's 128 square mile Marsh Creek watershed (itself in dire need of rehab).

In the waaaaay waaaaay back, though, before the advent of agriculture changed the way people related to their world, Native First Peoples lived off the succulent fruits of the Delta's bounty, established seasonal and permanent villages, tooled around in Tule canoes, hunted deer and gathered salmon and acorns.

They lived in harmony and intimacy with Bald Eagles, Grizzly Bears, Mountain Lions, Coyotes, Wolves, Condors, Rattlesnakes and Elk, thriving for 10,000 years of dream-time during which the only intruders for 500 generations were late-arriving Spanish explorers, French fur trappers and traders, and intrepid interlopers like Jedediah Smith and merchant marines from around the globe.

These wayfarers, looking for new trans-oceanic routes and various riches, sailed their seagoing vessels into the heartland as far as Stockton and Fresno, even, in the Central Valley, a dusty crop town (at the time) not immediately calling to mind a port-worthy destination.

As the gold fueled frenzy of the 1850s petered out, the losers in the Motherlode ore wars fled the played-out foothills to seek a more felicitous fortune in cheap farmland "there for the taking" in eastern Contra Costa County. Inevitably, "progress" took its "natural" course as enterprising, capitalistic men (civilized, by god) set about terraforming the land for enormous economic benefit.

These gold diggers turned potato diggers were soon making a killing off fertile vegetable, fruit and nut orchards (think of John Muir's genteel farmer days in Martinez), and in the process forever altering the hydro-eco calculus of Delta politics.

But first things first, of course. Cultural disruption had begun long before the mid-nineteenth century; by 1806, Ohlone villages no longer could be found in the East Bay.

Years of military occupation and forcible relocation, in tandem with ruthless efficiency in eradicating the Grizzly and Black Bear, Mountain Lion, Coyote, Elk and any and all creatures deemed threatening or verminous, forever ensured a Manifest Destiny victory. And not to be outdone in shooting all the fish in their cornucopia barrel, these geniuses killed off nearly every fur-bearing mammal native to the Delta.

Soon, Mother Nature, as Mother Nature is wont to do, reared her ugly head and flooded the holy crap out of the tidy plots of money trees, so to allay future disastrous flooding to their precious crops, the newly minted landowners imitated a resourceful local denizen – the beaver – and erected crude levees, creating a patchwork of raised, contained and protected plots in which to grow a substantial portion of the world's breadbasket of earthly comestibles.

No doubt about it, the advent of the White Man to the Delta was a major overhaul and game changer, ushering in the final death knell to the old ways of the ancient cultures.

The ensuing wetlands reclamation carried on, until by 1930 the winners in the land grab had constructed 57 islands and vastly transformed a half-million acres, rendering the Delta unrecognizable from its natural idyllic condition, in the waaaaaaaay waaaaaaaay back when Ohlone and Volvon Native Americans ran the show, in synch with natural rhythms, in harmony with all the creatures now wiped out. Sadly, it was not all that long ago, as measured in "many moons".

You'd been to Big Break a year ago, blown away by the beauty, surprised by the remote feel of the place fronting the 16 square mile town of Oakley, California (40,000 pop.), some 40 miles northeast of Berkeley, but cultural leaps and geographic bounds away.

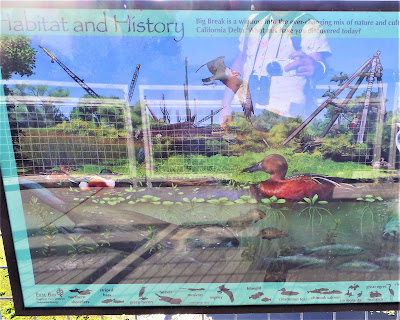

Big Break naturally sits at the aquatic ecotone, the boundary of salt and fresh water, where the "edge effect" supports diverse birds and other wildlife populations. Considered an "ecological treasure" by its protector, the East Bay Regional Park District, Big Break and adjacent areas are part of a 1970's era push for wetlands restoration.

Today, conservation partnerships with the Delta Science Center, Delta Conservancy, the Delta Protection Commission, Bay Delta Conservation Plan and other organizations have successfully rehabilitated shoreline, created wildlife habitat, and collaborated to build EBRPD's first recreational / educational center in four decades. A must see, of course, but somehow you miss it. Oh, well, there certainly will be a next time.

Big Break earned its name in 1928 when a levee protecting an asparagus farm busted and unleashed furious waters. From your canoe-bound perspective, it's hard to see evidence of farming activity or artificial berm construction, surrounded as you are by water, water, and more water, endless, rippling, swirling, amazingly blue water; bobbing around out in this vast expanse like a paper bag in the wind is not something to take lightly.

This is big speed boat territory, a place to ply manual craft with unerring caution and sober judgment. On temperate days, a brave kayaker might slip beyond the protected inlet at Big Break's pretty launch, but only fools – or boyishly enthusiastic older guys – would dare to tempt the fates and venture out into the big open void of a hybrid river monster pushing down with Amazon force and strong headwinds toying with you like a kite in a gale.

Like all good Sirens, Big Break invites a gentle launch in a mellow little cove to go forth and explore her blue expanse of plant-splattered, undulating water. The day has warmed considerably from the foggy chill typical of coastal Bay Area summer.

Here on the eastern edges of dry Contra Costa County, the sun is beating down on your un-SPF-protected skin, and relentless winds are pasting you to thin air. Mount Diablo and Morgan Territory Ridge, birthplace of Marsh Creek, loom to the south, almost unfamiliar landmarks from this rarely seen vantage point. Looking northeast invites a brilliant eyeful of stunning archway bridge and wind turbine "seascapes".

Settling into the canoe, you paddle rhythmically toward the middle of the protected inlet, at first so gentle and inviting an illusion; soon, you're a mere dot in the great blue beyond. And wouldn't you know it – big winds are kicking up, threatening to whisk you to places you don't want to go. It's definitely a struggle: the old men and the "sea".

Look, seriously, all hubris aside, this is a big, engulfing body of water that is absolutely frightening in its capacious ability to swallow you up, you in your little speck of a canoe, paddling futilely against 30 mph headwinds determined to blow your lackadaisical ass to Rio Vista or into the blustery waters of San Pablo Bay.

And then what?

Muscles burning, a pawn of the wind, you strong-arm the canoe to set your course. High fives and whoops ensue for your powerful, coordinated, sustained paddle strokes, because one let-up, at the mercy of a dictatorial capricious wind pattern, and you're a goner.

In your own little Walter Mitty heroic moment, you make it to far shore in a triumphant display of old-boy prowess and grit and steer the canoe to shelter and safety among calm, secretive, tule-choked areas where you hang your legs over the sides of the canoe and float motionlessly on shimmering cobalt waters reflecting wavy cattails and the deep infinity of a cloudless azure sky.

In these pretty, hidden coves and riparian areas, you're respectful and careful of breeding Western Pond Turtles who lay eggs in secretive incubators; of ecology-shaping beavers who build their dams; of muskrats and mink who reproduce and den; of playful otters who frolic and hunt. (For the record, you see a grand total of zero of these delightful creatures.)

These back channels offer serious down time from all the rigorous paddling – you wish like hell, though, for somewhere to dock and get out, stretch, explore on foot, jump in the water to cool off, find purchase on a sandy bar to kick back and bask in the sun.

You think about plopping overboard but getting back in would not be a pretty exercise as there really is no "bottom" to the peat-packed sinky soil of the Delta and capsizing the canoe would be not fun.

Besides, swimming is not permitted at Big Break (as if you didn't know), and especially not in protected beach areas, where hard to spot buoy signage announces PROTECTED AREA: STAY OUT! And rightfully so for this is Western Pond Turtle egg-laying territory and Yellow Chat nesting grounds.

However tempting, do not let the Siren of the protected, off-limits, undisclosed cove's gorgeous little scimitar shaped brown, sandy beach, rife with lip-staining blackberries, killer chill factor, and luscious swimming, lure you to break the law, by any means necessary. If you could even find the place again.

You're hoping to spot some cool birds and a furry aquatic mammal, like the hard-working beaver who lives in the Delta in great numbers, or a rarely if ever seen muskrat, or – just think! – an amazing encounter with a mink! Last time – first time – here, you spotted a pair of otters swimming near your docked canoe, a special sighting, and recorded your first-ever glimpse of the reclusive American Bittern, a wading predator heron known to frequent reedy habitats and keep under cover.

Being a major stop-over on the Pacific Flyway, bird populations, naturally, are impressive at Big Break, with up to 200 species recorded, including the sensitive Clapper Rail (recently renamed to Ridgway's Rail), Brown Pelican, and Yellow Chat.

Given the "edge effect" and general amenable nature of Big Break's variegated habitats, dozens of birds can be spotted on a casual outing without even trying: Herons, Egrets, Kingfishers, Black Phoebes, Doves, Sparrows, Warblers, Mallards, Bitterns, and countless other waterfowl and seabirds.

You get lucky and spot your very first Swainson's Hawk, an Argentine winterer known to patrol the skies in ever increasing numbers at Big Break. In a lazy back area, a couple of Great White Herons are perched on tree branches, and a Great Blue Heron flaps skyward, and – sweet! – a pair of Belted Kingfishers zip by like a CGI mirage, skittering off into their private, unknowable world.

Finally safe and sound and out of the canoe, it's time to wander around the beautiful place – Big Break's terra firma. Although small in extent, there's much to see and explore. Well-integrated eyesores of decrepit cranes and machinery have been left in place as reminders of a historic past.

Stretch your legs, bird watch, walk the fishing pier, investigate a small pond, check out the Visitor's Center and educate yourself, read the many interesting dioramas to get a sense of history and feel of place. For the meanwhile, though, you find a soft patch of ground perfect for throwing your body down to dreamily escape under breezy Cottonwoods for a well-earned rest.

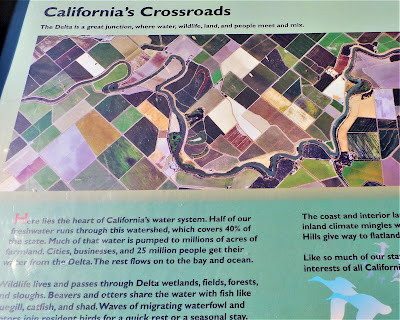

After a nice lunch, you're now finally roused enough to check out the Delta Experience – a 1200 square foot 3-D ground map with embedded satellite images of the region's cities – Stockton, Tracy, Galt, Lodi, Sacramento – showcasing the vast network of intricate arteries and waterways and how they flow and carry water through the Delta.

It's like the Land of the Giants, you straddling Mount Diablo and lording over a domain covering 1153 square miles of epic territory. Definitely a down to Earth perspective.

The story of the Delta continues to fascinate and unfold and will forever be controversial and attractive. Today, the system of levees and dikes protects a half million residents in rural and urban communities.

But fractious California water politics; long-tenured battles over ownership and rights; the fate of the endangered Delta smelt, striped bass, and salmon; worrisome contamination from heavy metal run-off (legacy from the Gold Rush days); pesticides and bacteria tainting; and invasive species.

Not to mention the specter of a decaying infrastructure eroding a thousand miles of decrepit levees, does not paint a pretty picture for the region's future. And now Governor Moonbeam is pushing for some kind of panacea plan to dig two massive tunnels to divert ever more water from the Delta to thirsty agricultural communities clamoring for their "fair share".

Political wrangling, Big Ag's deep pockets, "the best laid plans" – all are guaranteed to lose against Mother Nature's dictating whims, especially now with California in a fourth year of severe drought and life-giving Sierra Nevada snowpack at all-time lows, and the promise of an El Nino year up in smoke. Depreciated water flows in the Delta would not be good. A fifth and sixth year of severe drought would be unsustainable.

Water diversions would dwindle significantly, crops would fail on a catastrophic scale, a Mad Max local scene would explode tensions and fears, and a national calamity would unfold on a scale greater than the Dust Bowl.

Forget about saving water by cutting down on your luxurious 15-minute shower; the real "water shortage" problem is an over-emphasis on the unsustainable agro-industrial "breadbasket" model leading with the best of intentions to chronic misuse and waste, and an unfair allocation system that prioritizes ownership of our public water resources based on archaic and irrelevant precedents (to today's economic reality).

But short of California returning to pre-World War II days, population-wise; short of a mass overhaul of our food production system, where everything eaten is grown locally; short of hellish Mad Maxian visions, what's to be done? Two tunnels and a prayer seem to be the plan, but let's hope it's more than that.

Let's hope our noble stewards of the Delta – those many enumerated agencies who deserve our financial support and voice – will find creative and long-lasting solutions to preserving and protecting the great California Delta and its many wonderful environments like:

Big Break Regional Shoreline

LONG LIVE A CLEAN AND HEALTHY DELTA!

3 Comments:

Been there for the bass fishin....saw things in a different way here albeit via digital media.....nice article bud!!! --- M Guenza

Nice to see you back posting, Gambolin!

-N Aaland

Well done. Great read!

Post a Comment

<< Home