LAKE BERRYESSA: A Sneak Peek at Napa County’s Long-Abused, Recently Reclaimed Recreation Reservoir

A mirror image of willowy grey pines reveals an upside-down forest in crisp detail in the submerged reality. A sudden breeze sends a tide of ripples to blur out the Monetesque tableau.

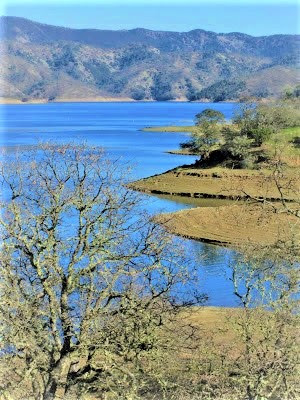

Opposite this secluded fingerlet, where a moment ago an egret flapped loudly and flew away, I stare out at a sheet of blinding blue water, mesmerized by rippling waves undulating across a 23 mile long, 3-mile-wide shimmering expanse.

We’re in the middle of a 2000 square acre wildlife area managed by Fish and Game, and, lemme tell ya, it’s a splendid and wholly unexpected, downright beautiful natural attraction heretofore ignored by Gambolin’ Man – like so much of eastern Napa, Solano and Yolo Counties and practically nine-tenths of the world.

The lake’s sun-drenched beauty and solitude take me by surprise. In a seriously deluded moment, or charitably, a highly imaginative one, I’m reminded, of all places, of Lake Titicaca on the Bolivia / Peru border high on the Altiplano of South America.

.JPG)

Apart from a very, very, very superficial resemblance, it’s presumptuous and ridiculous to compare a man-made impoundment with one of the planet’s oldest and greatest natural bodies of water; and yet this body of water right here strikes me fancily as being a nice little contender to a scenic slice of the famous Andean lake.

.JPG)

This mercury contaminated, artificial contrivance of a lake, but still one helluva beautiful lake – currently at low capacity – with its surprisingly eye-popping scenes of tranquil watery panoramas and rugged Coast Range vistas.

This reclaimed lake tryin’ to get a little respect. This supersized reservoir has earned a special place in my heart by virtue of its uncanny similarity, if only in my mind, to the much, much larger and infinitely more awe-inspiring lake at 12,500 ft. above sea level and thousands of miles away in another hemisphere.

The blinding blue expanse throttles me in my tracks. I’m shaking my head in amazement, nay disbelief, at the 1.6-million-acre feet lake spread out before me in what surely is a “Desert Southwest” landscape if there ever was one in Northern California.

A Big West scene of immense proportions, with reclaimed water as the centerpiece of a proud and ambitious hydrology project, a heritage of responsible management of precious natural resources for the good of the people.

If only that’s how things had played out at Berryessa over the past half century since Monticello Dam was built at the sandstone cleft of Devil’s Gate, impounding the “run-off” of once free-flowing Putah Creek, to slake the thirst and provide other hydro-uses (including agriculture and flood control) for the over-big and ever-growing cities of Solano County.

Just east of gentle wine country was once an ancestral place of propitious valleys and big creeks along whose banks the free-roaming aboriginal Patwin and Wintun peoples resided, thriving and prospering for centuries in the lush valley nestled between rugged Blue Ridge of the Cache Creek Wilderness Area and Cedar Roughs Research Natural Area.

A Wilderness Study Area (WSA) and an Area of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC) designated to protect:

“ . . . unique botanical values, including the world’s largest known stand of ‘genetically pure’ Sargent Cypress.”

Every plant necessary for food and medicine – and probably pleasure – can be found in this nook of California’s Coast Range – a prime reason why agriculture was never adopted by the Patwin or Wintun; they didn’t need to amid such abundant natural resources, in the lap of luxury, the land 'o plenty.

It’s also a breeding habitat of black bears, a rarity so close to the Bay Area. You can see why I’m shaking my head in amazement. Mostly, at never having known or cared about any of this.

The lake environs (mainly the west shore) is now a planned recreational short-term use area along scenic, gentrified stretches of the long tarnished, ignored ecological jewel that is Lake Berryessa.

One would never guess it from the solitude greeting us today, but one and a half million people visit the lake yearly. Today, hardly a soul in sight, and it’s prime wildlife habitat to spot birds, deer, raccoons, snakes and who knows what, if we’re lucky a mountain lion or rattlesnake.

But given the average 75 degree temperature in summer, you can bet this place turns into a party zoo for the masses, whose raucous excesses are confined to a small percentage of the lake.

You can bet the rest of this reclamation project is wide open territory for exploration if you’re able to hike or bike to some of the more remote destinations. Most of the west shore is or is being reclaimed, but the east shore retains an austere, forbidding, off-limits desolate feel to it – well worth a return visit to check out by bike someday.

The lake is named after two Mexicans, Jose and Sisto Berelleza, who squandered their vast holdings – a sprawling ranch – so it’s told, in gambling excesses, poor fools, leaving the land open for sale and development into farm parcels and a town or two, the biggest being Monticello, now under water along with other aqueous ghost towns and untold Native American sacred sites, with people’s lives upended, families uprooted, forced to sell or abandon, move on, relocate. It was like the dust bowl only with water.

Lake Berryessa as a destination has always been off my radar, owing to perceived reputation. But if you happened to catch it just right, in the off-season when it’s probably at its loveliest, and with Reclamation efforts paying off in full swing – well, Lake Berryessa fits the bill for a ducky outing, dishing up a generous amount of fun and recreation and providing new and exciting opportunities for exploring a pretty amazing place, really.

And with a still-fresh 50-year history steeped in power ploys and land grabs, dam building and flooding towns and sacred sites, antiquities looting, water projects for drinking, irrigation and flood control, bungled bureaucracy, misguided and derailed Public Use Plans, lax enforcement of regulations, public outcry, and finally, none too soon for the “general public” but a nightmarish realization come true for the privileged few – Reclamation.

Why was Reclamation necessary? Who were the privileged few? And how was such a status bestowed on such a marginal element of society?

Beginning in 1958, just seven concession contracts were issued. The Gang of 7, what did they do? They leased out 1300 “long-term use” permits to various families. Over the course of the next few decades, with the total population exceeding 1500, these “permittees” had managed to cash in on a neat little, well not quite a scam, but a neat little secret.

They scored big-time by signing long-term leases / permits to enable permanent settlement in oft-decrepit mobile homes and trailers along choice stretches of paradisiacal inlets and coves for some two generations.

Hey, more power to ‘em, right. Imagine having your very own private mobile home / trailer lot, situated on Elysian shores, living an oxymoronic million-dollar view life in luxurious bucolic indigence, you and your family and your descendants having the absolute run of the place!

Not a bad little secret, eh, but all good things must pass, and after forty years, whoever these people were, they were about to be evicted. The Bureau certainly had a sensitive, if ugly, battle to win these hearts and minds over, lest they just rudely evict them.

Ultimately, some people were aided (“mitigation”) in their relocation with various kinds of assistance:

“Reclamation will seek to identify and accommodate legitimate hardship cases expeditiously.”

“ . . . eligible permittees will receive priority consideration for permanent cabins or park models approved by Reclamation.”

Permanent? (Yes, permanent, but with temporal conditions and limitations.)

Can hardly blame 'em.

Can hardly not blame 'em.

In the Bureau’s eyes they were seen as an obstacle to progress, perhaps a public nuisance, certainly a hindrance to developing the goldmine of a tourist revenue stream that Lake Berryessa’s coves, inlets and beaches were waiting to become.

Patrolling and enforcing were endless sources of headaches for local health and law enforcement authorities, themselves long pickled in ineptitude, too understaffed and feckless for decades to do anything about it. Until beginning just three years ago, when the long-term use permittees' and concessionaires’ contracts were set to expire in 2009.

As early as the 1980s, someone knew something had to be done. The wheels of bureaucratic action ground at a glacial pace. But by 2000, Reclamation plans were gaining steam and becoming a reality – things were about to take a turn for the better (or worse, if you were one of the privileged few).

The U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation (Mid-Pacific Region), had been patiently waiting for the permits to expire, and was finally able to spring into action and act on the never-implemented, long-standing Public Use Plan (PUP)

In June 2006, three high-level officials in the Bureau signed the Record of Decision (ROD), a definite ruling on the Future Recreation Use and Operations of Lake Berryessa averring:

“ . . . privately owned trailers and mobile homes generally occupied acreage most suitable for development, particularly lakeshore sites, to the exclusion of campsites, picnic areas, and other short-term or overnight facilities.”

Reclamation encompasses a multi-use plan:

“ . . . to provide outdoor recreation facilities and services for the visiting public at Lake Berryessa which will accommodate a variety of aquatic-related recreation experience opportunities, to the extent and quality and in such combination that will protect the esthetic and recreational values and assure optimum public short-term recreational use and enjoyment, and social benefit.”

These contracts were initially good for “just” 30 years, set to expire in 1999, but in some incomprehensible deal back in the seventies they were extended another decade, until 2008/2009. For their part, the concessionaires claimed permittee residents provided their only reliable source of revenue for “business solvency”.

Okay, but still. What a deal! What a steal!

.jpg)

In repentance of their original sins to rectify a half-century of mismanagement and neglect, the Bureau adopted a five-pronged approach to develop, implement and manage:

“ . . . on an integrated, lake-wide basis . . . the widest practical spectrum of recreation experience for the visiting public.”

They pledged to preserve and protect natural resources in and around the lake; promote the safety and security of people and facilities; support the economic goals of surrounding communities; and maintain the opportunity for a fair and reasonable profit by concession contractors.

I have lived in California long enough, of course, to have seen Lake Berryessa, but not much of it, and only from high atop the Cache Creek ridges of the Coast Range, looking down from Cold Canyon Loop Trail, and being blown away by the view out there, down there, of pointy salmon-pink desert hills impounding the glory holes of Berryessa.

It was a Big West / Southwest scene, reminiscent of Sonoran or Mojave desertscapes around Palm Springs and Anza Borrega or – how about this – Lake Titicaca! (There he goes again!)

The exotic sight of a rugged lake basin ninety minutes from my doorstep produced an unexpected giddiness, as though oxygen-deprived, with epiphanies of wonderment spewing forth in streams of highfalutin hyperbole.

Which gets me to thinking – shouldn’t soaring heights of praising persiflage, vainglorious verbal apotheosis of natural beauty be reserved for Truly Incredible Places?

Does such a this little view down on a man-made lake in some piddly dry hills in a big stinky agricultural county warrants descriptors like “awesome / magnificent / spectacular / incredible / majestic”?

One particularly fine day a few weeks ago, we decided to ride our bikes around the lake – a pretty ambitious goal unless you’re a pro and can knock out 165 miles of shoreline, or a century plus of riding. Our pace today is leisurely and unhurried, just contentedly rolling along on the generally flat road, an easy 20 mile out 'n back, made notable by bird watching opportunities when and where they presented themselves.

And numerous dilatory sallies here and extended forays there to investigate the many gorgeous vistas that opened up; stopping a dozen times to get off the bike to see this and that, any and everything that catches our interest and attention.

A snarling freshly run over dead fox, poor helpless casualty of hurtlin' metal screaming down the highway.

A colossal rock blanketed in moss and ferns.

A marshy area with a Great Blue Heron stalking something with inimitable intent, focus and concentration.

Hilltop views of scenic slices of the blinding blue beauty framed with picturesque oak trees and chaparral / grassland mix.

Give me a day like today, a serene, barely any traffic, about as perfect for leisurely cycling as you can ask for kind of day, where you’re able to safely lollygag down the road, stopping whenever and wherever at a moment’s notice, or no notice at all – just a sudden throw-down-the-bike and check THAT or THIS out moment.

Or to stop and spend some time hiking around the small trail systems the Bureau of Reclamation has built at Smittle Creek and Oak Shores. Or sit by the lakeshore daydreamin’ about Lake Titicaca and past youthful adventures.

Lake Berryessa attracts for many reasons: blinding blue beauty, wildlife haven, bird lover’s paradise (a paradise for birds, that is), situated right square in the heart of the ecotone where the wetter Coast Range and the more arid Diablo Range transition, a sensitive environment providing for abundant biodiversity at the intersection of various plant communities and animal species unique to each range.

.JPG)

Endemic flora and fauna proliferate and prosper in this habitat, and yet you’d be lucky to see a hundredth of it on an outing. Still, the possibility of seeing any number of mammalian, reptilian, amphibian or insect species is unlimited.

As for birds, the potentiality of being able to knock off your life list of birds upwards of 50 species adds a special charm and competing purpose to the day. The many birds found at Lake Berryessa seek refuge, food and shelter in a healthy mantel of tree cover and shore-lined vegetation.

Over six types of oak trees grace the hillsides for warblers, blackbirds, jays, owls, wrens, sparrows, crows and hummingbirds to hide in – California Black Oak; Leather Oak; Valley Oak; Coast Live Oak; Interior Live Oak; and Blue Oak. (None of these specimens seem infected with Sudden Oak Death Syndrome, thank goodness.) In wildflower season, expect to find up to two dozen varieties coloring up the slopes.

Lake Berryessa has earned and deserves another visit. The east shore seems like a real adventure zone. Farther up the road, the north edges of the lake also merit a look-see, coming in from the Pope Canyon Road area. It has history, nature, beauty, wildlife, superb recreational opportunities.

An interesting if macabre side note: in 1969, the Zodiac Killer stabbed to death a couple picnicking at the northern edge of the lake at Twin Oak Ridge on an isolated spit of land usually submerged.

Surprising the couple out of nowhere, the mystery murderer was wearing (from Wikipedia):

“ . . . a black executioner's-type hood with clip-on sunglasses over the eye-holes and a bib-like device on his chest that had a white 3"x3" cross-circle symbol on it.”

On a lighter note, the legendary Bay Area rock band from El Cerrito, Creedence Clearwater Revival, wrote their great rockin’ tune, “Green River” about the 85-mile long Putah Creek which flows through two dams in the Berryessa badlands.