TAHOE NATIONAL FOREST: Braving Obstacles, Overcoming Hazards & Eluding Death in Search of Unnamed Waterfalls in Untamed Big Granite Creek Basin

.jpg)

Although in the moment it didn't even seem close, in grim retrospect, a brainless act atop a 200-foot waterfall nearly cost me and my companion our lives. One wrong move in these remote parts and you're a goner.

"Mrs. McGuire, I regret to inform you that your son has perished in a remote Sierra wilderness, unfortunately . . . no . . . we have not recovered his body."

.jpg)

Picaresque exaggeration? A lionizing "I cheated death" tale? Perhaps somewhat, but truthfully, the raw power of Mother Nature on display in the Big Granite Creek basin / wilderness in Tahoe National Forest was humbling, if not frightening.

.jpg)

One simple slip taking a "can't miss" photograph on a teensy, crumbling ledge; one numbskull miscalculation scaling a rock wall; one excessive moment of hubris-induced bravado . . . and you could perish in an instant.

.jpg)

This relatively small speck of earth on the Tahoe National Forest service map – itself relatively small speck on a map of California – could easily qualify as the most spectacularly beautiful and rugged creek shed – as well as the least explored and least accessible – in the Western Sierra Nevada mountains.

The upper (and lower) reaches of this largely unknown creek – whose basin / headwaters are located only a few crow-fly miles west of Lake Tahoe and below Donner Summit on Interstate 80 – is not a place many, if any, dare to tread.

.jpg)

If you did, especially at this time of year, when snow fields present an introductory first mile or two of tough terrain at 5000 to 6700 feet altitude, you’d better have excellent route-finding skills, superb map-reading abilities, possibly a GPS unit, or be lucky enough to tag along in the company of someone who knows the terrain expertly.

.jpg)

That was my ticket! An invitation from friend and de facto guide, Russell Towle. As Russell related in his narrative essay, Adventure in Big Granite Canyon:

.jpg)

"When it's time to visit the really wild places, I call Tom McGuire and beg him to make the drive, up, up and away from Berkeley, away from his beautiful wife Mary, and towards the North Fork, and Danger, Uncertainty, Difficulty."

.jpg)

Russell has been itching and scheming for just such an expedition for well nigh over twenty years.

.jpg)

Towle is to local Western Sierra Nevada foothills geology, history, botany and literary musings what Thoreau was to Walden Pond, Twain to the Mississippi, Muir to Yosemite, and Leopold to Sand County.

.JPG)

.jpg)

But that just speaks for how vast his great backyard is. Russell's explored everywhere, so he had been in the upper basin, but never managed to negotiate the additional thousand feet or so of hard going down to the untamed and as yet unnamed falls. It was not a daytrip. A minimum of two days was called for.

("We're not twenty-year-olds any more" as Russell reminded.)

This was tough, pitiless, intractable terrain, requiring the trifecta of athletic conditioning – stamina, flexibility and good balance – as well as a foolhardy imperviousness to the constant, aggravating pains of nicks, scratches, bruises and insect bites.

.jpg)

To successfully navigate this pristine glaciated wilderness, above all, would require pure focus, sheer resolve, almost as though in a "walkabout" state of consciousness.

For if you get to thinking too much about the many nearly insurmountable obstacles, it‘s enough to make you think twice: deep, shifting snow drifts that could swallow you. Cliff face drop-offs to chartless depths of bedrock.

.jpg)

Slippery crossings on skinny logs over rapidly moving, ice-cold water. Exhausting cross-country boulder hopping. Eye-poking out brush. The threat of snakes, mountain lions and bears. High altitude sun exposure. Gigantic granite boulders and booby-trapped talus slopes. Thick conifer forests, impenetrable riparian thickets and fields of brush to claw and scratch through.

.jpg)

Turned around? Lost your bearings? Hurt yourself? It happens. Just count your blessings you make it out in one piece.

A flurry of excited e-mails ensues. Russell (re)assures me:

"I have explored this whole area and hiked in Big Granite (upper part) several times. I have complete confidence, no doubt whatsoever, in our ability to get in there and back out unscathed."

.jpg)

Naturally, I accept the invitation – more like the challenge – to accompany him. It would be a magnificent traverse, a four-mile walk in the park, I imagined.

We'd first traipse – ha! – through high country reminiscent of Yosemite, then gradually we’d lose about two-thousand feet of elevation over a couple of miles to get to the glaciated-cum-volcanic depths of the geologically fascinating basin, where, for two creek miles or more, a series of increasingly scenic and ever more spectacular waterfalls shoot through the deepening gorge.

.jpg)

The main attraction is Big Granite Creek, whose waters boom and echo through the gorge like distant cannon shot. At this time of year, snow melt creates tumultuous flows during its wild course over 3000 feet of elevation loss, all the way to the North Fork American River.

.jpg)

I know Big Granite Creek from down there, at the confluence, at about 3300 feet above sea level, a perennially favorite camping spot.

.jpg)

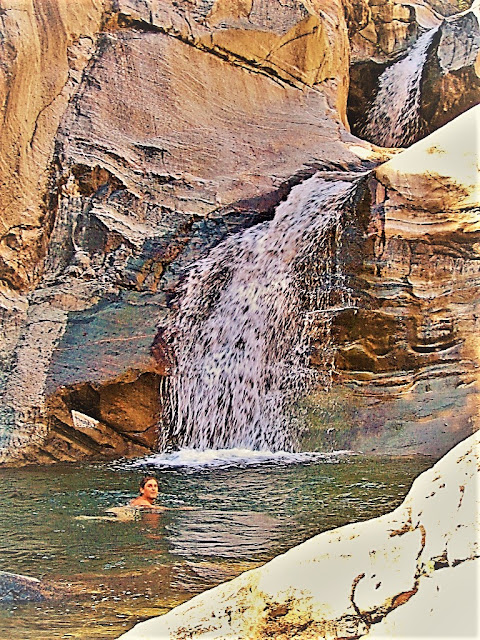

Just upstream from the confluence, Big Granite Creek has cut a nasty, twisted chute in the cliff wall – a hundred feet high, where crystal waters plunge into a wide, Hawaii-like pool before continuing on to the river where it debouches in a series of twenty- to thirty-foot-tall falls spilling magnificently into carved granite bowls and bathtubs.

A perfect summertime paradise, but one of the most punishing hikes imaginable in the Sierra foothills.

.jpg)

As lovely and dramatic as it is at the confluence, at a 1000 to 1300 feet or so higher up, Big Granite Creek takes on the grandeur of Yosemite. Here, the creek makes repeated plunges of fifty feet, one-hundred feet, three-hundred feet, with deadly velocity.

.jpg)

Our goal was to reach a soon to be legendary (perhaps only in our own minds) triple decker falls about a creek mile up from the confluence, or about four miles down from the I-80 crest.

.jpg)

If this untouched place (not quite!) were accessible, it would be a National Park. I kept saying to Russell, in astonishment, "This is our own private Yosemite!"

.jpg)

But for all intents and purposes, the Big Granite Creek Waterfalls Extravaganza is an off-limits paradise, a preternatural world so utterly inaccessible and remote that it might as well be a lost wilderness in Alaska or Patagonia. People simply do not very often, if ever, get down into – or up into from the North Fork – these reaches of Big Granite Creek.

.jpg)

There are no trails, except, of course, for those made by bears. No evidence of human activity, except, of course, for the scarred remnants in Section 15 of the 1991 clear-cutting disaster.

Russell and I wondered f anyone since then had been where we camped (at the top of the first of three eye-poppers). I’m convinced probably not even the Tahoe National Forest rangers themselves have seen or are even aware of these tremendous waterfalls (if they are, they're keeping it mightily secretive).

Russell’s closest and only glimpse of them had come just a week or two earlier, on the far south side of the river, from an old trail known as Iowa Hill Canal. I had written back to him, on viewing his jpeg, that it seemed like an insignificant thing, but given the distance Russell took the photograph from, it hinted at the fall’s immensity and grandeur.

That’s what got Russell excited, that and the tiny bunched together contour lines on his topo map which he read to indicate lots of dramatic falling water.

We exited I-80 at Kingvale and drove along a frontage road heading back west for a mile or so, then turned down a gravel jeep road that crossed the railroad tracks and eventually dead-ended at a snowbank in the middle of nowhere.

.jpg)

We organized our gear – I was going in light, with just a day pack and my sleeping bag strapped on with a bungee cord. I would make a sleeping pad with fir boughs. I had enough food, no water worries, and a pint 'o spirits for warmth and a much-needed shot 'o dream-inducing nepenthe at the end of a long, exhausting day.

And so off we set into the wild known / unknown.

At first it was fun going, we were full of steam and childlike enthusiasm, adrenaline fueling our every step of the way. The early morning snowbanks had yet to soften, firm enough to make the going pretty easy.

Coming back, later in the day, it was a grueling, different story!

In no time, we ascended the crest at Natalie Lake, situated at 6700 ft., right on the Yuba / American Divide, then made our way down the south-bearing slope of a sun-blasted granite dome.

Superb views of Devil's Peak (7704 ft.) and spurs of the 7976 ft. massif of Snow Mountain dominated to the east, while Cherry Point ridge rose to 6728 ft. to the west. Gnarled Western Juniper trees clung to pitiful perches.

.jpg)

These venerable denizens of harsh climes adapt to their sparse environment much like the Bristlecone Pines of California's White Mountains, able to survive for centuries upon centuries, living to be thousands of years old. Now there’s a real death-cheater.

We lost the snow, passing from the granite boulder / talus scene into a gentler territory of thick conifer forest and semi-frozen lakes. We skirted immense boulder fields, hopped over lovely Sierra streams, admired rugged landscapes atop apartment-sized granite boulders, and finally took a well-deserved lunch break at Natalie Lake where two lovely Western Tanagers romanced and entertained.

It seemed like a hop, skip and a jump to get to this spot. On the return, though, it took forever to get from "Tanager Lake" back up, up, up, over, over, over, through, through, through, around, around, around, to the car.

A couple of hours of tough bushwhacking later, Russell sniffed the air and turned with triumphant arms raised – we were at the waterfall . . . or, as we soon found out, we were at the first of three successive plunges of Big Granite Creek through the fabled gorge.

Russell describes our approach:

"The world ended, for just one thing. Some kind of monstrous cliff lay dead ahead. Beside us, Big Granite Creek raged though a broad channel hewn from the solid slate of the Sailor Canyon Formation. Quite suddenly it was a Force, and rather scary. It was just screaming down the canyon towards the Edge of the World, in a froth of pure white water.

I hurried southeast toward the Edge while Tom lagged near the first really violent cascades; he was still caught within his disbelief, tiredly agreeing with me, in his mind, yes, these are indeed great waterfalls. I began hollering for him to come look, but the river – for suddenly it seemed a river – was too loud."

We scouted out a camping spot – slim pickings on the rocky, uneven ground – and then turned our undivided attention to this bonanza of scenic wonders. The first waterfall spilled over a broad rocky lip, perhaps thirty maybe fifty feet across, and split into three thundering plunges of at least 250 feet to a wide, polished granite bed below.

Then 500 horizontal feet later the second of the falls drops an impressive 50 or 75 feet, crashing to a boulder-choked pool and then careens ferociously over the Mother of All Falls – this – God Almighty! – 350-footer! – Russell pegged it at a modest 200-footer! – issuing spray, rainbows, and so loud I was hoarse by the end of the day.

Of course, the middle and lower falls could best be seen from below, so to truly appreciate their tremendous power, we had to scramble down something like 500 additional feet of obstinate terrain. (And then back up.) But oh, was it worth it.

From higher up we could see maybe a third of an east-facing narrow Kauai-like ribbon of a cascade, just pouring down the opposite cliff face in a Fantasy Island-like series of falls and pools, perhaps an 800-footer, all told!

Although Russell soberly deemed this one a “mere” 600 ft. tall.

From where we now stood – near the base of the lower falls – we were able to take in the grandeur of the entire spectacle. Take it away, Russell:

"We descended a short steep cliff to a sunny broad ledge, maybe thirty feet below the top of the falls," Russell wrote. "It was all thunder and confusion and white water flinging free into the wild wild world, and cold spray wetting us. Amazing. Huge. Awesome."

After a restless night of sleep – wish I had my ground pad! – during which it got surprisingly chilly – we awoke at 5 a.m. and built a driftwood fire to heat up water for instant coffee before setting off to explore the nearby cliffs and return to the lower falls area again. No way was I going to pass on witnessing them a second, maybe final, time.

Sun-dappled patches of light began to gradually signal the impending heat of the day; finally, a brilliant sun breached the high ridge and showered us in warm rays. We had to ford the stream, since the only way down was on the opposite side of the creek from where we had camped.

Russell was leery from the get-go:

"There was quite a nasty tug as one crossed the deepest area, slightly over knee deep, and I felt the current literally slide me inches towards the falls; but one more step led to shallower water, and safety. I breathed a sigh of relief; Tom had had no trouble at all, it seemed, so it was just my nerves. Or was that ford more dangerous than I had imagined?"

.jpg)

We passed a couple of hours exploring about, looking for fossilized zoa in the rocks, discussing geology – well, Russell discoursed on everything from "the dirty granite, much veined with dark mafic materials and inclusions," to the "granite eggs, erratics dragged by the ice from farther upcanyon" – and generally lounging about and marveling agape at the four waterfalls.

Russell christened the triple-decker Upper, Middle and Lower Cherry Falls (for Cherry Point Ridge to the west), and the vertical ribbon he dubbed West Buttress Snow Mountain Falls (for Snow Mountain to the east). It was an impossibly exotic, magical and mystical place of big crashing waters.

A sacred, timeless place. And we had timed it just perfectly. Had we come a week or two earlier, the snowfields would really have been too much to cross, and a week or two later, the falls would be significantly diminished.

Knowing it was time to get a move on, we made our separate ways back to the top falls and met at the ford crossing.

We were stunned by what we saw – higher, faster moving water than two hours ago. Duh, of course. Russell estimated it takes about that long for the accumulated snowmelt fed waters to get to where we were. I looked up to see Russell flailing about in the middle trying to keep his balance and hesitated a bit before committing to join him.

I was barefoot, because I had loaned Russell my Tevas. I managed to get halfway across, but hesitated again, as Russell reached out and attempted to clasp hands. I wanted no part of it, even though he pointedly pointed out it was the thing to do in such circumstances.

He managed to retreat to shore, which I intended to do but instead slipped and, as Russell noted, "it was a miracle he was not swept down and over the falls." My foot instantly cramped up as I attempted to gain a life-saving purchase with three of my toes in a bedrock crack; luckily, I righted myself and struggled to join Russell where he stood staring at me helplessly.

We ended up fording a couple of hundred feet beyond and got a huge chuckle – not before chiding ourselves – for attempting to ford this raging creek a mere fifty feet from the top of the first falls.

And to think, I was more concerned about saving my camera than my own life! We packed it up and began the long slog out of the basin. We had 2000 or more feet of elevation to pick up, and four or more miles of trekking.

.jpg)

We scaled and trudged and crissed and crossed the landscape, overshot trajectories, and fought the thickets. The going got rough and the rough got worn-out, fast.

Coming back down the Yuba side of the divide, below Natalie Lake, through big snow, turned out to be the hardest part of the return hike. But we made it, one step at a time, and were none worse the wear, all in all, from my billy-goat eternally youthful perspective.

Russell, of course, had the last word on this:

"Tom and I suffered to visit these falls; I am still very sore, a day later. But, oh wow, oh my God, they are things of great wonder and beauty and power!"

.jpg)

Honoring Russell Towle:

Photo of Russell with arms outstretched in front of tree courtesy of Gay Wiseman

Check out more Gambolin' Man adventures in California's great American River canyons:

Grab a beer & settle in for some live (but shaky!) footage deep in the heart of NORTH FORK AMERICAN RIVER canyon country: