MOUNT DIABLO & MOUNT TAMALPAIS: A Natural History in Praise of the Bay Area’s Two Sacred Mountains

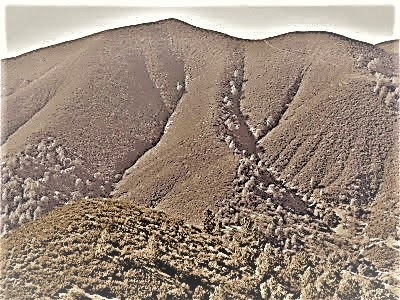

High above from an airplane window, thrilling views unfold of an inspiring landscape – a glittering vision of steely skyscrapers surrounded by forested greenbelt, impressive rocky ridges, rolling hills, hidden valleys, shimmering blue lakes, and endless miles of bay and ocean shoreline.

From a bird's eye perspective, the incomparable metropolitan Bay Area and its abundant natural beauty offer up a spectacular panorama made all the more notable by the presence of two imposing landmarks standing above and apart from lesser topographical features.

These are the twin “holy eyes” – the peaks of Mount Diablo and Mount Tamalpais. Together, but separated by 37 miles, they loom on the curvature of earth, anchoring opposite ends of this slice of Turtle Island-like geodetic monuments to creation.

The former, a double massif rising to 3849 ft., dominates eastern Contra Costa County and much of Northern California. The Mount Diablo Interpretative Society has proclaimed the heralded feature:

“ . . . one of California's most significant historical, cultural, and geological treasures.”

The latter is Marin County's highest point, a pyramidal mass of earth rising 2571 ft. out of San Francisco Bay, just off the San Andreas Fault at the continent’s geologically unstable western boundary. Of this iconic piece of real estate, Robert Louis Stevenson gushed:

"There is no place on earth so beautiful as Tamalpais."

Various Ohlone and Miwok tribes revered this earthly bounty and worshipped the prominent peaks as holy mounts for their cosmological significance and animist power. Both mountains were the Valhalla of prehistoric Bay Area, the ancestral dwelling places of the Creator Gods.

Mount Diablo was where the divine personages of Coyote, Eagle, Condor, Falcon, and Hummingbird reigned. These Supernatural Beings created the world after some catastrophic Diluvian event (sound familiar?) and spawned the races of humankind – the First People – providing them with:

“ . . . everything, everywhere, so they can live.”

"The animal-gods of Sacred Time still pervaded the everyday life of the world."

Despite centuries of oppression, disease, enslavement and the sad litany of abuse and cultural debasement at the hands of terrorizing Spanish colonizers and the Church, today’s ancestors of the First People, although few in number, are strong survivors and carry on the traditional totemic belief system of worshipping the mountains and their spirit entities and protectors. Mount Diablo has always been well known for its religious significance, a place where:

“ . . . the dead must cross or enter for purification before going to the land of the dead.”

John Peabody Harrington, an ethnologist and early expert on California’s native peoples, recounts in his 1929 field notes Chochenyo (Ohlone) consultants revering the mountain as:

" . . . a very powerful place that could mysteriously hide things, where large snakes were seen but could not be caught, and where spirits still danced and whistled in cemeteries."

In 1985, Mabel McKay, tribal elder, scholar and last of the “basketweaver dreamers” of the Pomo Indians (1907–1993), was quoted:

“I would listen as Jim [Cooper, an herb doctor who was born in the Diablo area] told my grandmother about how sacred Mount Diablo is. He said that as long as the mountain stands it will be a sacred mountain. He said that the entire mountain is sacred. He called it the Medicine Mountain. In his language it was called Kinchiiwi.”

The history of Mount Tamalpais is also steeped in legend and mystery, dating to a time when “men and animals spoke one language.” Various Miwok legends, handed down orally through the generations, recount stories of the mountain’s creation.

Another tells of the daughter of a Miwok chief, beautiful beyond compare, who was courted by the Sun God. They married and while journeying toward the heavens, carrying her, he tripped over Mount Diablo and she fell to the ground.

The Sun God, in his everlasting grief, turned her into a mountain – the Sleeping Princess – each night draping her in a cloak of fog as he moves across the sky.

Both "Medicine Mountains" have been known by various indigenous names, depending on the dialect spoken, and many namesake etymologies remain a mystery.

Mount Tamalpais, it is said, comes from "Tamal payis," Tamal being a generic name for the natives of the area. It has also been referred to, without reference, as "Pa-le-mus."

Mount Diablo, on the other hand, is a veritable gazetteer – the Chochenyo called it "Tuyshtak"; “the Northern Sierra Miwok knew it as "Oj-ompil-e"; the Central Sierra Miwok christened it "Supemenenu"; while the Southern Maidu (Nisenan) referred to it as "Sukku Jaman," or Dog Mountain.

The mountains have had various historic appellations bestowed as well. Mount Diablo has been known as San Juan Bautista, Cerro Alto de los Bolbones, and Monte del Diablo.

Mount Tamalpais has several hard to pin down monikers – Pico y Cerro de Reyes, Picacho Prieto, La Sierra de Nuestro Padre de San Francisco, and Table Hill. (The “Sleeping Princess” of alleged native myth is actually a contrivance of nineteenth century German immigrant hikers to the area.)

Besides rooted in peculiar creation mythologies, the mountain sentinels share a somewhat common geological heritage, even though Mount Tamalpais is born of the North Coast Range – wetter, foggier and more humid.

Unimaginable events – contorting, buckling, folding, uplifting – occurred over millions of years and have writ in the layering and depositing of rocks the story of these mountains’ creation born of severe plate tectonic upheaval.

On Mount Diablo, evidence of the ancient manifests in its quarter billion-year-old rocks, and when you happen to see a Paleozoic era dragonfly landing on the tip of a Devonian period horsetail, the earliest land plant, you are bearing witness to a 350-million-year-old relationship.

But, geologically, the mountain itself is a mere tyke. Somewhere between one and two million years old, it came into existence eight million years after volcanic eruptions tore through the East Bay.

However long its catastrophic birth took for the mountain to assume its present shape, it is still alive and growing to the tune of a few millimeters each year.

Mount Tamalpais similarly owes its existence to tectonic activity deep within the Earth when the North Coast Range began uplifting some fifty million years ago as the North American and Pacific Plates collided, and pressurized tension forced subterranean crust to burst through the core with mountain-making fanfare.

With its sweeping ridges and rollicking slopes falling away to the ocean, and its twin East Peak and West Peak flirting in cerulean realms, Mount Tamalpais stood fully formed, tall and isolated at the coast range’s southern terminus, long before Mount Diablo was ever a gleam in Coyote-God’s eye.

Both mountains’ inner core is composed of Franciscan rock – chert, sandstone, shale and serpentine. The rocks on the slopes and summit of Mount Diablo were formed on the bottom of a shallow sea that once covered the Bay Area.

Domengine sandstone formations (tafoni), occurring at lower elevations, were laid down when the sea receded in the Eocene. Today, eerie and intriguing wind and water caves lend a desert Southwest feel or Alabama Hills ambience to places like Rock City and Castle Rocks.

Serpentine outcrops characterize both mountains. Their geo-chemical make-up (rich in iron, magnesium and nickel, and lacking in calcium, molybdenum, sodium and potassium silicates) has contributed to depleted soils lacking essential nutrients, allowing for only a handful of certain plants, found nowhere else on earth but their incubator habitats on some remote hillside or shady canyon, to adapt and flourish.

These rare species include native perennial grasses and wildflowers, and on Mount Tamalpais, a unique thistle, and the endangered Jewelflower of the mustard family, with fewer than a dozen occurrences noted.

Over on Mount Diablo, endemic flora includes the yellow fairy-lantern (a delicate lily), the diminutive Mount Diablo sunflower, and the “Holy Grail” of flower chasers, the Mount Diablo buckwheat, rediscovered in 2005 after a 70-year absence by UC Berkeley grad student Michael Park.

Today, the buckwheat is safely propagated and continues to grow in secret spots on the edges of the mountain’s chaparral zones.

The “island mountain” environments, responsible for endemic flora and fauna, naturally host classic California low elevation habitat such as chaparral, grasslands, oak woodlands, vernal pools, and riparian, enabling shared biodiversity with particular localized adaptations.

.jpg)

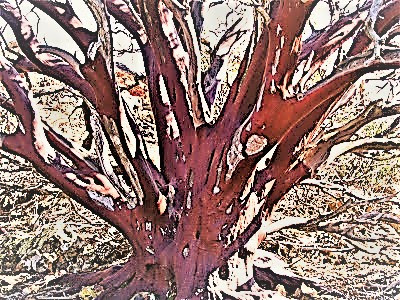

Each mountain lays claim to its own special (and rare) variety of manzanita – not surprisingly, named Mount Diablo Manzanita (Arctostaphylos auriculata) and Mount Tamalpais Manzanita (Arctostaphylos hookeri ssp. Montana). The Mount Diablo variety has pinker blossoms than other varieties.

Botanists believe that the characteristic stripping away in ribbony tatters of the creamy chocolate colored bark is a defense mechanism to shed parasites and mold. No matter its cagey survival strategies, all manzanitas have found a way to adapt in the rocky, rugged soils of the two mountains.

Often, seemingly dead specimens, skeletal like sculptures with scraggly branches poking up, perished in fire or claimed by old age, refuse to relinquish the gift of life and provide a grafting base for another one to sprout. Death – and life! – intertwined, co-existing, one and the same.

Also found in abundance and much appreciated by human observers and the many animals, birds and insects who symbiotically depend on each other for survival and adaptation, are California buckeye and stream bank loving red and white alders and – Bigleaf Maples.

Also found are parasitic Pacific Mistletoe; the bright red berry bush, toyon; pungent smelling California bay laurel; multiple species of pines and oaks; and the minty-smelling coastal scrub plant communities of chamise, chinquapin, artemisia, coyote brush, blue witch and black sage.

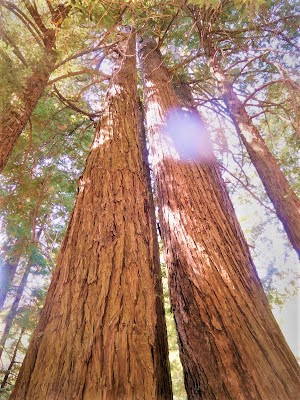

Mount Tamalpais supports a unique species of dwarf cypress, a delicate orchid (Calypso), and, famously, boasts extensive preserves of old growth Sequoias at Muir Woods National Monument.

Droves of photographers and admirers flock to the mountains’ slopes and meadows in anticipation of seeing profusions of wildflowers in season. After spring rains, abetted by a few days of that famed California sunshine, colorful explosions of fiery orange poppies, bright red Indian paintbrush, pink checkerbloom, golden monkeyflower, bluedick, daisies, mariposa lilies and purple lupine light up the hillsides and meadows.

Throughout their short life span, dozens of species of butterflies (many rare) and bees are attracted to the sweet-smelling flowers laden with succulent nectar which they gather up in the process of helping them propagate.

While it’s not uncommon to see many types of insects, a few reptiles (watch out for rattlers!), amphibians, mammals and avifauna – ground squirrels, Steller’s and blue jays, hawks, quail, hares, vultures, lizard, frog, deer, any of the thirteen species of bats hanging around cliff faces, or the occasional gopher snake or coyote.

Most of the animals roaming the back country of both mountains are unseen and elusive – who among us has seen (more than once or twice) a bobcat, cougar, fox, badger, skunk, jackrabbit, Coast horned lizard, shrew, long-tailed weasel, tarantula, opossum, kingsnake, and the endangered Alameda whipsnake?

If you happen to espy any of these animals, you are extraordinarily patient, invisible of presence, non-perfumed smelling in laundry or personal hygiene products, light of foot, slow-going and nearly immobile, or maybe you’re just plain lucky to be in the right place at the right time.

Most of these animals are very weary of humans, and so remain out of sight, hidden, venturing forth only at the crepuscular hour to prowl around.

Both mountains enjoy a world-class reputation for birding – herons, egrets, shorebirds, woodpeckers, swallows, swifts, flycatchers, wrens, warblers, hummingbirds, quail, owls, larks, wild turkeys, turkey vultures.

Also, many easy to spot raptors such as red-tailed and Cooper’s hawks, northern harriers, falcons, kites, and golden eagles, ever on the prowl for a tasty meal of vole, mole, rat, mouse and pocket gopher. Birdsong enlivens everything along the trail!

Mount Tamalpais has a flourishing steelhead / rainbow trout migration spawning history. Originating high up on Mount Tamalpais, these streams – Lagunitas Creek being the most famous – speak to a greater preservation of pristine conditions and more successful restoration efforts in Marin County. Mount Diablo cannot lay claim to a spawning migration today.

But, optimistically, assesses that evidence exists:

“ . . . for the historical use of Mt. Diablo Creek by anadromous O. mykiss as a migratory corridor.”

Mount Diablo’s other drainage system, Walnut Creek Watershed, the largest in Contra Costa County, once supported large spawning migrations, and a few still manage to straggle up into lower Walnut Creek.

So, there is hope for the steelhead / rainbow trout coalition, but not much.

There is no greater reward for the hiker or biker than attaining the hard-earned summits for the ultimate payoff – world-class panoramas of California and the West Coast.

Since the earliest of times, through historic settlement days, people have been drawn to the mountains as though by magnetic allure, for it is the closest we can get to experiencing heaven on earth or a return to our “Buddha nature” connecting with our primal selves.

After all, and above all, as their mere presence and existence attests, mountains of all shapes and sizes beckon us to climb them, as John Muir urged, to:

“ . . . get their good tidings . . . the mountains are calling and I must go.”

Even Dr. Suess exhorts us one and all:

“Today is your day! Your mountain is waiting. So . . . get on your way.”

From atop Olympian Mount Diablo, on a (rare) clear day it is possible to see 35 of California's 58 counties, encompassing an area 40,000 square miles the size of six New England states. Far-flung views with the naked eye can be had of the snow-capped Sierra Nevada crest, and 200 miles distant, the 10,462 ft. Lassen Peak in the Cascade Range is visible.

With radiating 360-degree views, every reference point and natural feature in the 9-county, 7000-square mile Bay Area is telescoped in the thinnish air.

Etched in minute precision, details are laid bare and stark beneath the behemoth mountain’s purview, revealing an intimate topography of finger-splayed estuary systems, the sinuous San Joaquin River delta, and sprawling ridges and voluptuous hills.

Even that “insignificant” little blip on the southeast horizon, 1702 ft. tall Brushy Peak, stands out at the edge of Morgan Territory as a prehistoric beacon, a gathering place at the juncture of the San Francisco Bay Area, the California Delta, and the Central Valley for dozens of passer-by tribes coming to trade, socialize, gamble, and share stories and laughter.

To the north/northwest, an impressive phalanx of dozens of 2000+ ft. tall peaks, between 90 and 126 miles distant, serrate the horizon in a single unbroken ridge system; the biggest of these include the Mayacamas (3250 ft.); Mount Saint Helena (4343 ft.); Mount Konocti (4299 ft.); Hull Mount (6873 ft.); Cold Spring Mount (3587 ft.); and pinpointing high above the others, Mendocino’s Snow Mountain topping out at 7056 ft.

To the south/southeast/southwest, the cloud-poking peaks of the Diablo Range and the Santa Cruz Mountains come into view – Mount Hamilton (4213 ft.); Junipero Serra (5862 ft.), 123 miles away; Mission Peak (2658 ft.); and Loma Prieta (3791 ft.).

Across the expanse of East Bay Hill lands, the volcanic remnant of Round Top at Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve stands out at 1763 ft. with nearby Grizzly Peak at 1754 ft., and Vollmer, the highest point in the Berkeley Hills, at 1905 ft. Rocky Ridge’s 2000+ ft. spine at Las Trampas Regional Wilderness is a revelation of modest grandeur in the near foreground.

And there in the glittering distance, across the bay, lies the Golden Gate Bridge, and the silvery city of San Francisco, with Mount Tamalpais shining eternally and resplendently across the strait.

From the empyrean vantage of this coastal promontory, gazing out beyond the rugged Headlands, the prevailing views are striking of blue ridge sylvan slopes angling to the sea, the mirage of San Francisco floating on a cushion of low-roaming clouds.

Beyond, the Farallon's 30 miles outside the Golden Gate, the inland flanks of the mountain harboring several hidden lakes (reservoirs), the summit of Mount Burdell (1555 ft.), to the dim wilds of Mendocino National Forest.

Beyond, naturally – impossible not to notice – sits the crowning jewel, the twin peaked silhouette of Mount Diablo, emblazoning the horizon in purple mountain’s majesty. The "little mountain" might not look like much from here, but it is nearly forty miles distant, and so proportionately, it looms with an unusual grace and presence.

During the changing seasons, the mountains take on personalities suited to their whimsical natures. Though rare, winter storms can bring freezing temperatures and dustings of snow to the higher elevations, 2000 ft and above. Occasionally, three feet of snow can dump on either mountain.

When this happens, the picturesque backdrop of snow-capped mountains in the Mediterranean climate of the Bay Area is an incongruous sight, a magnet for drawing people to the mountain who otherwise might not give it a second glimpse.

Add snow, though, and suddenly you’ve got something exotic and dramatic to crow about and play in.

Springtime on the mountains is Earthly Paradise (don’t let the ticks and poison oak deter you) – wildflowers grace the hillsides and meadows, and a sense of renewal and freshness pervades the air as the hills are transformed by rain falling to soak the parched earth.

Creeks are recharged and burble merrily along, waterfalls boom in the canyons. When the water’s flowing, expect magic and miracles around every bend. Sunlit dappled pools, rushing cascades, water swirling through carved chutes, towering redwood trees, fern-cloaked stream banks, mouthfuls of sweet edible Miner's lettuce. Summers on both mountains are wicked hot.

Mount Tamalpais offers shadier woodlands and, with its lakes and perennial streams, shelter from the day’s blazing temperatures is never far away. A sweat drenching hike leads to a place of solitude and peace, with small wading pools here and there to soak your feet in and while away a lazy day at Steep Ravine, Cataract Falls, or Cascade Canyon.

The shady, cool retreat of Muir Woods offers respite as well from hot temperatures. Plenty of places to escape to, relax, enjoy a picnic, and revel in the day's languor.

Over on Mount Diablo – its name now hinting at the hellishness it can turn into on a blistering summer day – the 20,000-acre park is often closed due to extreme fire danger from tinderbox conditions. There are not too many places to hide.

Coyotes hunker down in the tall grass. Hawks and vultures lazily circle; even the ground squirrels stay in their burrows. You can die on this mountain if you venture too far without enough water or let the hubris of your bravura overdo it and heat stroke claims you halfway up the mountain trail.

For the Goddesses of Diablo will surely exact their price for the privilege of sharing her natural wonders, splendors and secrets. Venture with caution – and respect – always.

Mount Tamalpais is a gigantic bulwark of a ridge system whose high point culminates in the 2571 ft. East Peak. Its 6300 acres abound in natural wonders, cultural resources, and recreational opportunities, with over 60 miles of hiking trails, towering Redwoods, booming waterfalls, rustic cabins and environmental camp sites.

This wild land serves as sanctuary and get-away to millions of people. Zen poet and circumambulator of the mountain, Gary Snyder, notes:

“ . . . Tam is a model for appreciating nature close at hand and not needing a total icon of pristine wilderness to get your attention.”

I second the sentiment, but consider more importantly what Galen and Barbara Rowell, in their fly-over reconnaissance missions, revealed, startlingly, to be:

“ . . . unbroken forest . . . more than over the national parks of Costa Rica.”

Roadless or not, I decree “Tam” to be a slice of veritable wilderness in our back yard!

Same goes for ol' Dog Mountain.

Kingly Mount Diablo stands alone on the horizon, an irregular topographical feature, a conspicuous presence unmatched by nearby smaller formations.

In 1860, J.M. Hutchings, who wrote Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California, declared:

“ . . . almost every Californian has seen Mount Diablo. It is the great central landmark of the state. Whether we are walking in the streets of San Francisco, or sailing on any of our bays and navigable rivers, or riding on any of the roads in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys, or standing on the elevated ridges of the mining districts before us – in lonely boldness, and almost every turn, we see Monte Diablo.”

"Clear and cool. Beautiful silvery haze on Mount Diablo this morning, on it and over it – outlines melting, wonderfully luminous."

Nobel Prize Winner Eugene O’Neill, a resident of Danville, swooned:

"Mt. Diablo, a mass of purple in the morning. Nature is always lovely . . .”

Gambolin’ Man has also written of the mountain:

“It’s no wonder that Ohlone peoples north, south, east and west all turned to Tuyshtak for spiritual renewal and sacred cosmological allegory as the birthplace of the universe. Or that it was later plotted as the fixed meridian for surveying vast portions of California land. And there it sits, the dominant Bay Area landmark . . . known and loved by many, but ignored and taken for granted by the vast majority.”

Mount Diablo's broad contours especially compare to a “real” Sierra Mountain. Take Mount Tallac (from the Washo, “Dala-ak,” great mountain), which rises majestically near Lake Tahoe to a sky-kissing height of 9735 ft.

Now, subtract the lake’s surface elevation of 6335 ft., and that leaves a mountain 3475 ft. tall – just about the same size as Mount Diablo using the same formula of subtracting its height from its base elevation above sea level.

The point being – and no further need to defend – Diablo and Tam are legitimate mountains, complete with distinct topographical and ecological zones at varying altitudes, hosting endemic flora and exposing vestiges of a violent geological past.

They harbor creatures great and small, hiding charming hollows and intriguing nooks and crannies, and whose deep wellsprings create beautiful water plunging, flowing, pooling, and, finally, everyone's criterion, offering up stellar views in all directions.

What more can you ask of a mountain?

Self-contained, amidst unmitigated urban surroundings, the mountains seem to exist solely for the weary and overly citified, beckoning us from our artificial enclosures to come explore and seek respite from the harried day in the shady nooks of the mountains' welcoming bosom.

No agenda is a fine agenda. Time ceases to exist on the mountain redoubts, or takes on a different meaning, a vague construct of less urgency and importance. On the mountain, you're able to forget about petty trifles and mean concerns.

There is nothing to remind you of the things you cannot have. There is nothing or no one to be but your joyous self, in the sanctity of the mountain setting.

The mountain gives freely of its generous spirit.

The base existence of “carnal incrustations” of which John Muir always sought to shed, and the world “late and soon” which Wordsworth thought was “too much with us," fades below, out of sight and mind, when lost in meditative reverie or intoxicated on the drunken glee imbued by nature’s distilled spirits.

Yes, the unfettered pursuit of fun and adventure is what captivates and draws us to these special mountains, but there is something more.

We seek what our ancestors have always sought in retreating to places of eternal power – personal enlightenment, communion with higher powers, spiritual renewal.

And, not least, to replenish our drained souls.

Check out more Gambolin' Man posts on the magic, mystery and majesty of Mount Diablo & environs:

Read more about Mount Tamalpais:

DAY HIKING MOUNT TAMALPAIS STATE PARK (2006)

AWESTRUCK AT MUIR WOOD NATIONAL MONUMENT (2006)

WALKABOUT UP MOUNT TAM'S FOOTHILLS ON PINE MOUNTAIN (2009)

AWESTRUCK AT MUIR WOOD NATIONAL MONUMENT (2006)

WALKABOUT UP MOUNT TAM'S FOOTHILLS ON PINE MOUNTAIN (2009)

Read bird-related posts wandering about the riparian nooks and crannies of Mount Diablo State Park: