PINNACLES NATIONAL PARK: Primo Hiking Along the West Fork of Chalone Creek Among Towering Rock Formations Inspires Awe & Reverence

Feathery blue late winter days

– or is it early spring? – cry out for an exotic setting. How about tropical

lassitude on the Big Island or a quick Baja excursion to the Sea of Cortez.

Failing that, could you believe an unexpected Southwest style adventure!

Yes, desert-like environs awaits not far from the raw Bay Area – just head inland,

south, less than two and a half hours driving distance. Beyond do you know the

way to San Jose. Past Morgan Hill and the unseen rugged hills of Henry Coe

State Park to the east.

Zipping by the quaint historic California biker town of

San Juan Bautista. Blowing past garlicky Gilroy. Barely a nod to the famous

Steinbeckian town of Salinas. Farther south than you ever remembered down a

nasty stretch of Highway 101. Finally, at the stalwart town of Soledad, you

pull off the freakin’ freeway, tense and with a bladder about to burst.

Soledad, California, population 26,200, 190 feet above sea level in Monterey County; claim to shame: two notorious prisons and the 13th of Alta California Missions – Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad. (Although it's doubtful city leaders consider either institution anything to be ashamed of.)

The other – Salinas Valley State Prison – has been in the business of stockpiling criminals since 1996. As for the Mission and Padre what’s-his-name . . . well, the inspired mission of California’s Missions is a well-documented history of complete subjugation and abnegation. Soledad Mission, founded in 1791 at the site of an Esselen Indian village on the Salinas River, brought resident Indians into the fold with a firebrand quality of religious zealotry.

Translation: the padres were engaged in the insidious business of genocide, whether they saw it that way or not. If, say, you happened to be a member of the venerable Chalone clan, and heaven forbid were corralled, coerced or cajoled into giving up your “old ways” in order to be baptized in a “civilized” lifestyle in the Mission, you were a casualty of that genocide.

Make no mistake, it was a concerted effort at the highest levels of the ruling theocracy to destroy Native American culture. Combined with horrendous decimation caused by lethal Euro-diseases like smallpox and influenza, native peoples (not just in the Gabilan Range and California and all of the United States, but of the entire Western Hemisphere) were robbed of their heritage in a Manifest Destiny campaign of cultural destruction, enslavement, superior firepower, disease and death.

For the area’s once strong numbered and proud Costanoan tribes, who lived in the Salinas River Valley and along the rivers and creeks for thousands of years, it was an almost overnight eradication of an entire lifeway – and this at just one of California’s 21 Missions stretching across two-thirds of the state.

As for Soledad, marred by agricultural stench but sandwiched between the very pretty Santa Lucia Mountains to the west and the Gabilan Range inland – lo, the Pinnacles – well, the fortunes of this down on its heels town may have taken a turn for the better recently.

Translation: big changes afoot. “The potential boom to our local tourism industry,” the Mayor gushed in a press release on February 13, "holds the potential of fueling Soledad's continued growth well into the future. As city leaders, we must do everything we can to seize upon this historic opportunity to maximize the benefits to our local businesses and our many residents."

To accommodate so many new visitors – mostly global tourists who now think the place is worth seeing because of its enhanced status as a National Park – the giddy municipality is planning major infrastructural projects, such as installing route-finding signs, building a by-pass, and embarking on a social media blitz to trumpet its “Gateway” signature and proximity to award-winning wine areas.

With the coming economic developments and infrastructural enhancements befitting access to a new National Park, things are about to change in a big way in these parts as the National Park Service and community politicians and businesses gear up for the avalanches and crushes and jams of humans flocking to behold the unique rock formations that are, naturally, truly, no kidding, amazing to behold.

Hopefully, the sensitive ecology of the Pinnacles – and its newly designated Hain Wilderness – will ensure extra special measures and cautions to protect this most sacred of places. In February, Ledesma, outgoing Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar and US Senators Barbara Boxer and Dianne Feinstein feted a delegation of elected officials in a christening ceremony, vowing to preserve and protect it for all time. Finally, politicos doing something good!

For now, things are still relatively unhurried. At the trailhead parking lot at 10 am, though – ready for a big dose of solitude in the countryside – you’re mildly dismayed at the number of cars already parked. In fact, the lot is full, crazy busy at mid-morning with hiking parties scurrying around their vehicles, organizing daypacks, etc.

Okay, it is a Saturday, but still.

It’s a-comin’, folks . . . enjoy it while you can!

And aren’t there more trail options into more spectacular landscapes – otherworldly rock gardens of spires, hoodoos and fins jutting skyward, attracting climbers from around the world. Plus, it seems like the East Entrance is a nicer drive and 45 minutes closer to boot. Still, the West Entrance entrances . . .

There’s plenty of parking in the overflow lot, which isn’t so bad, since a connector trail runs a quarter mile through a sweet meadow you’d otherwise not take in, through a blessed sanctuary of chaparral and rock where Western Bluebirds seem happy as can be flitting from bush to bush.

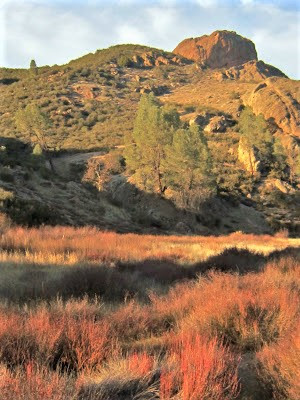

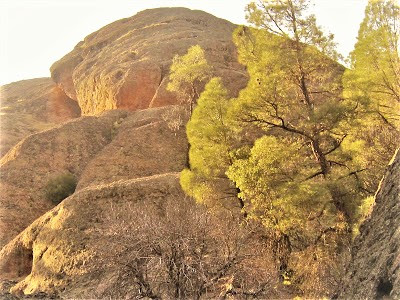

Resurrection Wall, a little old 2000-footer, situated in this dry, rocky, rolling chaparral country, imbues a special wilderness allure to the West Entrance approach.

You can’t put your finger on it; maybe it’s the enticing trail names: Juniper Canyon, High Peaks, Balconies; maybe it’s the Southwest style look and feel of things – the park brochure proclaims it to be a land of “massive monoliths, sheer-walled canyons, and boulder-covered caves.”

If that ain’t Southwest, nothing is. In the case of the Pinnacles, such descriptive language is not farfetched. The Pinnacles, as everyone might not know, painstakingly migrated up along the San Andreas Fault from the deserts of Southern California over the agonizingly slow course of some twenty million years.

A third of it – the Neenach Formation – stayed behind 195 miles southeast, while the bulk of the volcano was carried – pushed – to its present location.

But not before having sank beneath the surface and then exposed to the world by wind, rain and ice action which sculpted the rock formations we see today. What a spectacle Neenach must have been at 15 miles wide and 8,000 feet tall, before being split apart by the Pacific Plate and conveyor belted to its present location.

Grok this: In several millions more years, it will be up near Seattle!

Reinforcing the Southwest analogy, or perhaps belaboring it, the landscape and topography defy conceptions and challenge expectations of Central Pacific Coast Range Californian scenery, in this case the seemingly pedestrian Gabilan Range.

What marvels could this 805 square mile enclosure hold, apart from the oddly out of place Pinnacles?

With several peaks registering 3000 ft.-plus elevations, the Gabilan is no slouch of a range; it is constantly being shaped and reformed by tectonic plate action from the San Andreas Fault where it straddles two competing crustal plates bumpin’ 'n grindin’ up against one another in a death squeeze.

The Gabilan Range has been exposed to the same severe erosive forces which created the Pinnacles itself, so no dissing this little Range which, like Cache Creek, Sutter Buttes, the Macayamas or some other unsuspecting string of mountains, surprise and entice with their rugged ridges, high peaks, valleys, forests and creeks.

Anytime you get 3000 ft. elevations, it’s big-time country, no matter the altitude, which, in the Pinnacles ranges from 824 ft. to North Chalone Peak rising to heights of 3,304 lonely feet in a little visited area.

Yessiree, the Gabilan Range holds such marvels and secrets as to be worthy of comparison to a veritable desert Southwest ecosystem, a place where north meets south, west meets east, where floral and faunal communities from each zone intermingle and survive endemically. And where seasonal water and springs hold the key to life.

Once on the trail, with the various hiking parties having dispersed, you relish the relative solitude. It’s perfect mid-February 65 degree weather – early spring for sure! You couldn’t ask for a better day – one of those “will it rain or won’t it” kind of days that turns into a splendid summery sensation of mild temperatures and warm sunlight coaxing shy poppies and springy paintbrush out of the ground.

Ten in the morning is a heavenly suspension of time in the fantastical fairy landscape. The pretty meadow fronting the Grand Spectacle of the Pinnacles (you can see them rising castle-like) is aflutter with birds taking advantage of the gentle conditions.

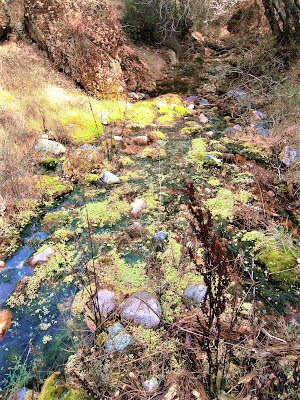

You veer off the trail avoiding a well-outfitted group of Japanese tourists marching by, one of them curiously glancing back to see what it is you’re investigating down among the tangles of brush and willows. Nothing much, just a dried out algid ribbon of the West Fork Chalone Creek.

What could be more – exciting?

The piss-ass nothing little creek is a mere backdrop, an afterthought, invisible, actually. A foot bridge farther up presents a perfect opportunity to just stop and take in the scene, but no one stops or pays one iota of attention to this subtle riparian ecosystem, this elusively apprehended water element manifesting in a Mediterranean climate disguised as a desert Southwest paradise.

No one is paying one iota of attention to the West Fork Chalone Creek! And why would they – it’s just, as you have said, a piss-ass little creek. And yet, no matter where manifested or how powerfully, the allure of sacred water draws you to explore and plumb its magical mysteries.

As it hasn’t rained in a while, long narrow stretches of the West Fork have dried out into splotches of puddles in a rocky bed strewn with boas of festooning moss, with dribs and drabs of water pooling modestly at the base of colorful lichen-encrusted rocks.

Notwithstanding its declared piss-ass nothing status, this creek holds many charms and mysteries, some seen, others intuited – but mostly the West Fork Chalone Creek is a precious refuge for the vital ecological role it plays in supporting endangered habitat for 149 species of birds, 49 mammals, 23 reptiles, 6 amphibians, 68 butterflies, 40 dragonflies and damselflies, nearly 400 bees, and many thousands of other invertebrates.

Long may you flow, Chalone Creek!

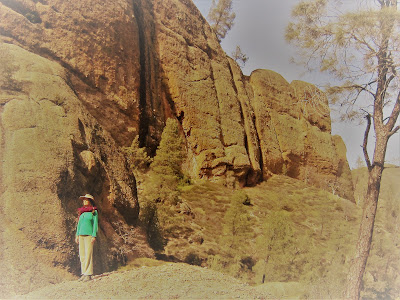

After a good deal of such dilatory wanderings, barely covering any ground – which is the true definition of “making good time” (and “making time good”) – you pick up the pace a bit, following Balconies Trail as it winds in and out of sight beneath the towering ramparts of Machete Ridge and the surreal Balconies Cliffs – a monstrous Canyonlands-like formation whose contours shift and rock your world at every turn in the trail.

It feels SO DAMN GOOD to be out moving in the chipper air, breathing gobfuls of fresh O2, and enjoying a spectacular hike in a world-class place, you just want to scream and shout! So you do!

AIIIIIIIIIAAAEEEEEYYAAAEE!!

The loop is more of a lasso – a five miler and not very strenuous but still mildly punishing, owing to your beat-up feet. Flushed with adrenaline, you don’t even feel it until back at the car. Out on the trail, you’re lit up like your thirties.

What a beautiful place!

A sumptuous day of changing scenery, mind-blowing topography, unexpected microclimates, diverse vegetation, and intergraded ecosystems of woodland, riparian, chaparral, and grassland. But, as you say about every place, it can’t get any better than this. Not even smack dab in the middle of Canyonlands! (Yeah, right!)

You take a breather in a copse of stunted black oak to admire a balancing rock sculpture – a huge pink egg resting on an even bigger pink egg. The configuration doesn’t photograph well, but you obsess anyway over getting a good shot. Then you happen to look up and spot a couple of black specks circling distant minarets – could they be California Condors?

Despite the distance, you’re pretty certain judging from the nearly ten foot wingspan. This magnificent and magnificently ugly bird, nearly driven to extinction, and still threatened today, is on the rebound thanks to park wildlife management officials and other agencies and parties who have rallied to save it from the brink.

This ancient creature, once common as a turkey vulture across a vast domain, is now trumpeted as a signature recovery species in its endemic soaring and roosting territory – the American Southwest, and, yes – the Pinnacles. Through your fancy new binoculars, you’re able to catch a white triangular patch under a wing, the identifying mark of the rare Gymnogyps californianus.

Thrilled at the remote encounter, you can barely put the binos away to continue on. At a bend in the trail, you stop for another five minutes to admire a rock wall bathed in radiant pastels of chrome, chartreuse, and mandarin colored lichen – a polychromatic sampling of just a few of the nearly 250 distinct kinds of lichen that paint the Pinnacles’ weather-beaten rocks.

You’ve now come to the loop portion of the amazing trail system. At this juncture, you’re a mere six-tenths of a mile in, but it’s been 3492 feet of trail packed with head-shaking marvels and jaw-dropping distractions.

A loop option takes you up and around on Balconies Cliffs Trail, or down in and under along Balconies Cave Trail, where Chalone Creek slashes through the entombed chasm – cave-like conditions created when overhead boulders the size of freight cars loosened in earthquakes and erosive forces and came crashing down to block sunlight from ever again reaching the narrow gorge.

The talus caves are open most of the year, flashlights required, and respect commanded for the primary residents – thousands of bats from 14 different species. Currently, the Western Mastiff Bat is occupying the cave, but that doesn’t let it stop you from scrunching your way through constricting walls and low overhangs, then slithering down the cold smooth lap of rock into the bowels of the cave for a moment or two alone in the dark, dank tunnel.

You wonder if a bat is going to swoop out or if you’d lose your footing and go sliding down your rump 20 ft. for a nice souvenir or two. The reverie is short-lived as a party of three kids and a woman come shambling by, followed by people shining bright lights all over the place, their amplifications ruining the dark sanctity of the underworld mystery cavern.

Gambolin’ Gal’s waiting patiently for you in the shade near a Gaudiesque configuration of piled up rocks. Emerging from the shadowy world of the talus caves, it is so bright you need to put on your shades.

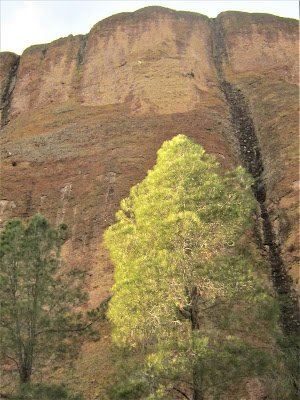

Onward you go, hand in hand now, through a sparse forest of California buckeye, dogwood, and other near-to-bloom trees framing picturesque views of stark crags and ridge lines, contours highlighted by the changing light conditions.

The creek bed is now a fossil of itself, with occasional hints of the precious stuff shining up from neglected nooks of the creek like broken pieces of mirror. You linger to admire the mis-en-scene, agog at the simple beauty of things, the solitude and quiescence, even with “all the people” around.

Up on Balconies Cliffs Trail, you’re in Hiker Heaven, a splendid area with big views of craggy spires and funky fins, of love-it-to-your-bones big rolling rugged chaparral hill country. Much of the Pinnacles, you’ll have us know it, is just that.

Trails leading along the various forks of Chalone Creek – North and South Wilderness Trails – lead into this big back country of the Gabilan Range, into an untouched world, remote enough, ironically, surrounded as it is by Monterey County and San Benito County development money.

As the trail wends down, one fork leads to the exit of the talus caves, which you explore later, and one forks to the Old Pinnacles Trail which traverses three miles along the West Fork Chalone Creek all the way to the East Entrance. The level path makes for some mighty easy, leisurely strolling through an enchanting bay / oak / madrone / poison oak / dogwood arboretum.

Lethargic water funnels in the creek along whose banks and flood plain you’re hoping for a bonanza of birds. You meet a pair of birders who rattle off a number of cool sightings, but you, you have to content yourself with the juncos and scrub jays.

With your feet starting to burn, you put ‘er in low slow gear, relishing in the “sainthood” of your saunter – a slow purposeful, meditative walk, in stillness and in silence, appreciating the very tiny miracles found along the creek as it meanders through a Diablo Range-like landscape reminiscent of the remote Orestimba Wilderness in Henry Coe State Park.

You see frog eggs; deer tracks; a single ladybug; hairy coyote scat; a cilia of a worm on a nano-thin strand of web. The creek opens up, a dry rocky stretch, barely flowing, but still endlessly fascinating – this piss-ass nothing little dried up creek crisscrossing through the land.

You can’t explain your attraction, but it’s clearly evident by the dozens of bad photos you take trying to capture the creek’s ineffable beauty and magnetism.

Sun sunk low behind Machete Ridge, time to head back. No more dilly-dallying, lingering, and hanging out; no more protracting every possible moment into something grander. After quickly checking out the talus cave exit, you return via the high loop trail, which isn’t so bad, really.

For with out ‘n backs, what you see coming back is completely different from what you see on the way in.

Late afternoon – or is it early evening? – lighting creates an alpenglow sensation on high rock walls, defining sharp contrasts to oddly shaped rocks. It takes forever to make it back, but finally you do, after one more extended session in the can’t pull yourself away from beautiful meadow.

You salute Resurrection Wall. Lengthening shadows reach to the edge of the sun-struck façade of Machete Ridge.

You can’t take your eyes off it, so you walk backwards part of the way, slowly, multi-tasking by watching for birds and taking in the grandeur of it all. Only now, sitting on the edge of the car trunk, shoes flung aside, do you feel the pain and ache in feet, ankles, shins, knees and hips from all the walking, bushwhacking and climbing.

Recovery time: a couple of days, small price to pay.

Got to do it again soon, because the secret’s out:

This place ROCKS!

Read Gambolin' Man's other post extolling the marvels and wonders of Pinnacles National Park: