MAINE BACKWOODS: On the Trail of Thoreau’s 1846 Wilderness Experience in the Great Katahdinauguoh Expanse

"What is most striking

in the Maine wilderness is, the continuousness of the forest, with fewer open

intervals or glades than you had imagined. Except the few burnt lands, the narrow

intervals on the rivers, the bare tops of the high mountains, and the lakes and

streams, the forest is uninterrupted."

- Henry David Thoreau

After many weeks desperate to escape the stranglehold of urban jungles, the prospect of tramping about in bear and moose country through uninterrupted forest, swimming naked in pristine lakes, and scaling to the bare tops of high mountains for far-flung vistas of a primeval landscape sounds like inspirational medicine for a city-ravaged soul.

The imagination swoons with idyllic scenes of country brooks, flower-filled meadows, and merry frolics “over unmeasured zones of earth, bound on unimaginable adventures.”

Lest the backwoods of Maine be, as Thoreau often conceded, a burnt hellscape “made out of Chaos and Old Night,” a “universally stern and savage world,” a pestilential "no man's garden,” a terra incognita “vast, Titanic, and such as man never inhabits.”

In 1846, Thoreau explored the Maine backwoods led by two experienced settlers / outdoorsmen he'd met – George McCauslin and Tom Fowler – along with Fowler’s unnamed brother

and two boatmen. Notably, the expedition party forging up the West Branch of the Penobscot River, excluded a couple of Penobscot men (one being Louis Neptune), whom Thoreau had recruited but ended up losing track of after a supposed meet-up down the road.

|

| Joseph Attean Requested credit line: Image courtesy of Special Collections, Raymond H. Fogler Library, DigitalCommons@UMaine, https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/spec_photos/3326 |

Thoreau didn't mind, and actually felt "lucky to have exchanged our Indians" for the two anchorites McCauslin and Fowler, reputed to be "the best boat men on the river." Thoreau's view of Neptune and his cohort was uninformed and condescending:

" . . . the Indian is said not to be so skillful in the management of the bateau. He is, for the most part, less to be relied on, and more disposed to sulks and whims."

Over the course of two subsequent trips to Maine, Thoreau's attitude toward indigenous people, while not perfect, had evolved substantially to more deeply appreciate, respect and understand them less as romanticized "noble savages" and more realistically as cultured and civilized men, and doubtless his superior when it came to surviving in the wilderness and co-existing with nature.

The 1846 expedition

paddling up and down rivers, and fording the rapids, and plying across "thoroughfares" of lakes, all told, was a strenuous effort to get to the base of 5,267 ft. Mount

Katahdin (aka Baxter Peak). Thoreau's curiosity not sated, he returned in 1853 for his epic moose hunting experience with guide Joseph Attean (pictured above), and was again

lured back in 1857 by the “call of the wild,” this time accompanied

by a “particularly steady and trustworthy” Penobscot man named Joe

Polis, who led him on a fantastic excursion from Indian Island:

|

| Penobscot Man of the Wilderness and the World Photo courtesy of The Penobscot Perspective — Then & Now - Thoreau - Maine Thing Quarterly (visitmaine.com |

“ . . . into the fabled heart of the Maine wilderness: Moosehead Lake, across the Northeast Carry, into the West Branch of the Penobscot River, into Chesuncook Lake and Umbazooksus Stream, over the legendary Mud Pond Carry, into the Allagash waterways before spilling down Webster Stream into the East Branch of the Penobscot.”

Thus Mel Allen begins his 2015 story in New England Magazine (Thoreau's Maine) recounting the previous year’s retracing of the 325-mile expedition marking the 150th anniversary of the 1864 publication of The Maine Woods, Thoreau’s classic narrative of his three epic trips.

|

Thoreauic8 preparing to shove off on epic retracing of route Photo courtesy of Little Outdoor Giants |

Though at times haughty and indifferent to the subtle survivalist knowledge and ways of understanding and interacting with the natural world that Polis possessed, Thoreau was quite impressed with his guide, whom he continually referred to as the “Indian”. Polis, he observed, was a self-sufficient man of nature (also of the world, Thoreau duly noted).

Polis was completely at home in the deepest wood where, despite his steadfast reputation as a "wilderness icon", Thoreau felt threatened, lost, removed from and often flummoxed in his ability to relate to Polis as his equal, though he was a sophisticated culture bearer and shaman whose concept of "wilderness" was far different from Thoreau's in that he did not set up artificial constructs between primitive/wild and civilized/cultured as in Thoreau's mind.

Unlike the white man, he existed in the natural world as part of, not apart from. In Polis' (and in all indigenous peoples) ontological and practical view, "wilderness" was merely a place where they lived and hunted, camped and sheltered, tracked game and fished. Polis told Thoreau, "It makes no difference to me where I am." A riddle which apparently was lost on or not appreciated by Thoreau, for his stance was, "Such is the Indian's pretense always."

Surprised, or perhaps envious, Thoreau noted that Polis required little more than an axe, gun, blanket and his mainstays of tobacco and pipe to find comfort and security in a wilderness Thoreau perceived as unforgiving and trackless. But it was hardly that. As Frank Speck, a Penobscot scholar and anthropologist, noted:

" . . . it appears that in the old days the whole interior wilderness was covered with a network of trails, allowing little reason for anyone to get lost for very long in the woods."

In a scholarly article titled The "Domestic Air" of Wilderness: Henry Thoreau and Joe Polis in the Maine Woods, author Tom Lynch calls into question how such an intricately organized landscape can be called a wilderness. He wonders:

" . . . what basis exists to call a landscape so intricately organized a wilderness. In calling it one, however, Thoreau must avoid awareness of the degree to which the Penobscot had engineered and in a sense domesticated the landscape. To understand the landscape as the Penobscot do would deprive Thoreau of the thrilling wilderness experience he is seeking."

In hindsight, it's easy to knock Thoreau for failing to realize something 20th century academics concluded over a hundred years later.

At one point their campsite conversation turned to the ways of route finding and orienteering, how easily one could get lost and turned around in the middle of such "trackless" woods. The renowned Walden Pond naturalist figured the Indian “found his way very much as an animal does.”

He expressed amazement: “How do you do that?” Polis responded: “Oh, I can tell good many ways.” Thoreau pressed for more information. Polis (presumably in a mischievous arrogant tone) said, “Oh, I can’t tell you. Great difference between me and white man.”

Over the three trips, Thoreau and his companions, with and without Indian guides, ventured into a “bran new country; the only roads were of Nature’s making.” The Maine woods, relatively unexplored (by white men), comprised a vast territory abutting gigantic swathes of the Canadian provinces of Quebec and New Brunswick, and contiguous with the mountainous states of New Hampshire and Vermont.

They ploughed into a dreamy and primordial landscape of unbroken forest, shimmering lakes, rugged peaks, flowery meadows, and crisscrossing waterways of sweet flowing creeks and tumbling rivers often made impassable by violent rapids and logjams, but rich in a bounty of flora and fauna that sustained native tribes – “People of the Dawnland” – as well as (the Abenaki) who call themselves Alnôbak, meaning "Real People" – for millennia.

Then appeared “awanoch” (white man). Despite Thoreau’s poetic observation that “the aborigines have never been dispossessed, nor nature disforested,” awanoch soon engaged in the usual trickery and gaslighting characteristic of the aggressors' full-on assault: land dispossession, disease, and cultural upheaval, strife and displacement of Maine’s four native tribes, the Micmac, Maliseet, Penobscot, and Passamaquoddy. (In June 2020, they formed the collective Wabanaki Alliance to promote tribal sovereignty.)

In the Abenaki tongue, awanoch translates as "who is this man and where does he come from?" From the time of the Norsemen’s trans-Atlantic crossings in the 1200s (perhaps earlier) to explore, trade and harvest timber, through occupations and settlement during colonial times, to Thoreau’s sojourns, to modern days as Maine’s native population has dwindled to barely 10,000 strong, the presence and impact of awanoch on the people and land of Maine replicates the usual sad story of Manifest Destiny in the expanding United States of America: the “God-given right” of awanoch to take what they reckoned to be theirs.

From such a short-sighted, greedy perspective, the natural resources and rich bounty of the land were being wasted, unused, therefore ripe for the taking and developing, subjugating rich cultural heritages, and raping, pillaging and plundering the land. Though he was selective in what he chose to lambaste, Thoreau bore witness to the “mission” of such men in his early day:

“ . . . like so many busy demons, to drive the forest all out of the country, from every solitary beaver swamp, and mountain side, as soon as possible . . . we shall be reduced to gnaw the very crust of the earth for nutriment.”

No doubt the Abenaki might also have asked of awanoch:

“ . . . who is this man and why doesn’t he go back to where he came from?”

Too late for that. During the first third of the 19th century, the Penobscot's significant territorial presence had begun to erode. A Penobscot witness to the invasion at the hands of:

" . . . bad and wicked [white] men, aggressive squatters, woods workers, thieves, arsonists, and murderers who caused tremendous harm to the Penobscot people and their livelihood."

The scholar Jacques Ferland has written of frontiersmen arriving with their:

" . . . cultural baggage of utter disregard

for Native American rights. Intimidation, coercion, physical aggression,

theft, vandalism, arson, even murder assumed less gravity . . ."

These state-sanctioned Manifest Destiny-driven "newcomers" (invaders) deprived the Penobscot of their fishing privileges, plundered their forest of valuable timber, swam cattle onto their islands, squatted on their sacred land, built saw mills wherever they could, and indiscriminately killed off moose, deer, and fur-bearing animals revered and utilized by Penobscot hunters, and pressed, with the power of the state, the Indians to “cede” more land.

From the perspective of a Penobscot observer, dispossession and subjugation looked like this:

“What do white men suppose we must think, when we see they wish to take from us one piece of land after another till we have no place to stand on, unless it is to drive us, our wives, and our little children away? But if so great and so free a country as this would exterminate us, we have no chance any where else; we, or our children, must sooner or later be driven into the salt water and perish.”

" . . . white society for its role in Native dispossession and shift blame for the factional dispute to supposed internal tribal struggles and flawed moral character."

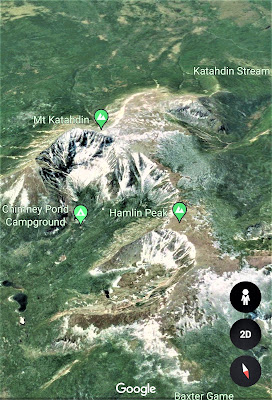

Our own “expedition” into the Maine backwoods pays homage to the thirty-year-old Thoreau and his guides’ journey in 1846 by batteau – "a sort of mongrel between the canoe and the fur-trader's boat" – across the paradise of lakes, up and down a confusing matrix of disappearing streams and turbulent rivers, in a quest to attain a route up the great mountain known as “Ktaadn” – from the Penobscot meaning “highest land” – in what is now Baxter State Park.

|

| Summit of Katahdin kworth30, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons |

_katahdin%20from%2010000%20feet%20up.jpg)

" . . . through all the débris and underbrush at the foot of the mountain . . . [rather than] . . . the short way instead of climbing by the Slide, where all West Branch parties ascend to-day."

What a dummy you are, Hank! Okay, so friggin' what if he laid a northeast course instead of by the Slide. Is that such an erroneous error in judgment that we should hold him accountable for untold blunders and pratfalls? Instead of perhaps an easy saunter, not so memorable, up to the peak, by going a more unintuitive or difficult route, Thoreau was able to experience a hallucinogenic, supernal interaction with the forces of nature – "rock, trees, wind on our cheeks! the solid earth! the actual world!" – he might have missed on a more leisurely tack.

Ours is but a mere dipping of the toes into this sparsely populated region for a couple of days, nothing remotely compared to the expedition mounted by the “Thoreauic 8” scholars, planners and Penobscot tribal members profiled in Mel Allen’s article. These daunting adventurers relied on Thoreau’s detailed journal notes, written for the "benefit of future tourists" to find their way and replicate the route taken 168 years ago.

As a result, they were able to ply the same treacherous white-water rivers, ford the same strenuous “carrys”, paddle the same placid mirror lakes, and sleep on the same stream banks to re-live and re-tell the story of Thoreau’s immersion into what expedition organizer and Senior Program Director for the Northern Forest Center Mike Wilson calls the “Alaska of the East.”

We can only imagine what the 325-mile journey was like for the original explorers and now the Thoreauic 8, paddling and trekking across immense tracts of north-central Maine's rugged topography, in the big country of the Chesuncook, the near chartless backwoods and rivers, lakes and tributaries of the Allegash and East Branch of the Penobscot River, and other notable points of arrival and departure where, Thoreau was to learn, nature is:

“ . . . more grim and wild than you had anticipated . . . swarming with myriads of black flies and mosquitos, more formidable than wolves to the white man.”

The Alaska of the East remains a remote world unto its own, a land held sacred by its original inhabitants, a place similar to and yet a universe apart from how Thoreau experienced it. Penobscot tribal historian James Francis, who partook of the commemorative expedition of the Thoreau 150, bridges this gap of history and cultural distance.

He notes in Allen's article the importance and timelessness of Earth Wisdom traditions and respect for the land and its eternal sustaining powers:

“The river is the heart of our culture . . .

the water that surrounds us flows from

Katahdin and ties us to our landscape.

From water comes life.”

Driving away from the urban centers (Bangor, Augusta), the landscape gradually becomes devoid of strip mall towns, fast food joints, trucker stations and billboards sparsely dotting the lone highway. Looking out the window of blurred scenery whizzing by, nearly 4,000,000 acres of (semi) continuous forest, the impression is easily gotten that not much has changed since Thoreau’s time.

Yes, it's that time!

Time to ditch the devises and connectivity,

time to log off . . .

and connect with the Earth!

Baxter State Park, located in the heart of the Katahdinauguoh (“mountains about Ktaadn”), is an outdoor lover’s paradise, especially on a beautiful late summer day. But regardless how remote or far away a place is, hundreds of people are out and about and will find their way there.

That includes us too. If you can’t beat 'em, then join the thousands of outdoor enthusiasts and nature lovers seeking their particular versions of fun and adventure. Fortunately, a motherlode of serenity and solitude awaits, for the 210,000 acre Baxter State Park offers ample space to disappear in – 220 miles of hiking trails, lakes, streams, forests, peaks, bogs, and meadows to explore. After all, we're all hoping to find our private slice of paradise.

We arrive fairly late in the day to do much of anything except leisurely stroll around Abol Pond, bird watching and basking in the waning sunlight, admiring the reflections of trees in the shimmering water's surface.

Our first night sleeping outside the park, we find a suitable little spot, hidden off a back road, that shelters us during a surprisingly cool and dewy evening.

Ravens fly into branches above, peering down on us with mocking cackles, gaping with their coal black beady eyes, hoping, like the squawking Jay, to swoop down for a crumb dropped on the ground.

In the distant gloam, we hear the dusky calling of a rarely seen bird – Eastern Whip-poor-will! – whose sweetly lilting call does indeed sound like its onomatopoeic namesake:

WHIP! POOR! WILL!

WHIP! POOR! WILL!

The Audubon website notes the Whip-poor-will's plaintive mantra can go on and on – "a patient observer once counted 1,088 whip-poor-wills given rapidly without a break."

We hear a motorized rumble getting louder by the second – a large vehicle approaching, now stopping, now headlights blaring supernaturally, now muffled voices, now tittering laughter, now thumping muted bass, then unnerving us, a flashlight shining in the trees and down on our tent. We sigh a thankful relief when they finally move on down the road, out of earshot.

Early next morning we take in the sights of Upper Togue Pond, outside the park proper, enjoying a leisurely breakfast on a conveniently situated picnic table facing the great North Country body of water.

Less a pond than a huge lake, the watery environs slowly take shape as a veil of mist lifts to reveal a distant forested island and tree-lined main shore. A slow moving boat far out on the water shimmers like a mirage. A fish hawk dives for a meal. Where is the Loon?

Deep beauty and silence greet us here. Finally, we marvel at a pair of Loons screeching across the sky as the unfolding light show welcomes daybreak. It is a perfect morning, quiet, utterly without a reminder of civilization or hint of human activity . . .

Until – our reverie is shattered by an obnoxiously loud road grader revving up at a station house. It’s only 6:30 in the morning, but no time is too early to smooth the muddy and rutted road so the tourists – arriving by 8 – can drive safely to their destinations in the park. I suppose that includes us, too.

We pay the entrance fee and head straight to the Katahdin Stream Trail, already hopping with about a dozen people gearing up, all hoping to gain, if not the summit (hah!), then at least a decent view of the massif poking out of the clouds.

We anticipate a human traffic jam on the super-popular Katahdin Stream hike, toe to toe with others tramping up and down the trail – even though there are over forty other peaks to climb in great Katahdinauguoh expanse! – all hoping to summit the impressive peak at the fabled terminus of the Appalachian Trail.

But overcast conditions prevent us from espying the famous peak which Thoreau also only barely glimpsed owing to:

“ . . . its summit veiled in clouds, like a dark isthmus in that quarter, connecting the heavens with the earth.”

So it's not as bad as we'd imagined, since the weather has turned keeping most people off the trail.

Even so, we're always looking to take a detour down a spur trail, or impulsively bushwhack up a little freshet, maybe scurry across a rocky slope, always hoping to spot something unique or odd. Then our efforts are rewarded when we find ourselves alone in the quiet wood, bathed finally in elusive serenity, with nature’s sounds of silence our company.

Gentle wind whispering in treetops (a phenomenon known as psithurism); babbling brook coming down from its mountain spring; and lovely tweets and twills from birds in the branches – all to brighten our spirit, calm our mind, soothe our soul, and restore our senses.

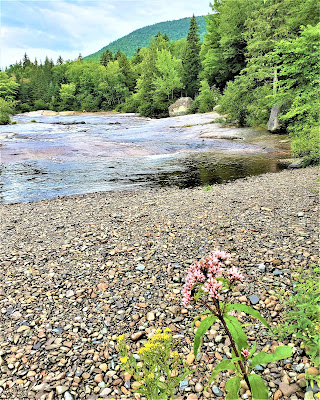

We hike up and up along the winding trail skirting Katahdin Stream, flush with wonder and a vicarious thrill, the trail being just long and hard enough, to feel as though we are on a much bigger adventure – the last leg of the 2,185 mile journey (of 5,000,000 steps!) of the Appalachian Trail hike from Springer Mountain, Georgia to the sublime summit in northern Maine.

Two miles into our hike, a bridge has been washed out and the “considerable mountain stream” (doubtful the one referred to by Thoreau as “Murch Brook”) is too forceful for us to dare to cross, so we stop to rest and take in the glory of our surroundings in this wet, wild world.

Where we forest bathe in the serenity of a sylvan sanctuary, and admire the beautiful creek spilling down from high spring-fed swales and subterranean cisterns on the great mountain’s unreachable slopes, squeezing through narrow slots and flowing out into more open areas, now suddenly sing-songing over pretty colored rocks and winding through gentler boulder gardens before disappearing into a dense green tangle of chartless forest.

We’re waiting things out, eating a snack, hoping to continue up higher toward the peak for stellar views. Hikers come along, momentarily stymied, then make the crossing with poles or big sticks, seemingly unconcerned with the threat of inclement weather that could wreak havoc higher up.

We decide to chill where we are before making our way down to more hospitable climes – slowly, deliberately, for there is so much to see easily missed along the way.

Every little ground sprouting creation bursting forth with lustrous color and bold texture. Little mushrooms of all shapes and sizes, and ghostly, ephemeral fungi stop me in my tracks as I bend over to examine their inherent oddness, their infinite uniqueness. I stick my nose close enough to whiff a heady, musty odor in this glistening wonderland of sensual earthy aromas.

Once down at the trailhead, we see a group of young women through-hikers fawning over a rustic 70-something year old guy with groupie enthusiasm. He’s donned in ragged hiking apparel (decidedly non-REI) and outfitted with an old-school pack strapped to his wiry frame.

Hands-down it’s gotta be Maine native and hiking legend George "Billy Goat" Woodard (profiled in 2016 in Billy Goat the Hiking Legend), but he could have been any number of such age-old (and old age) characters who have spent their lives in relentless pursuit of "finding themselves" (or "losing themselves") in solitary vision quests traversing America's great through-hiking trail systems.

I edge close to the group on the pretext of observing a pretty which-kind-is-that? Warbler – actually, no pretext needed! – and overhear their animated conversation about “summiting” Katahdin, some having done it yesterday, some in anticipation of a big push starting early tomorrow, given better weather.

|

Appalachian thru-hikers Patches 'n Passport |

Well good for them (even though the Thunder God “Pamola is always angry with those who climb to the summit of Ktaadn”), but despite a difficult last-leg slog of 4000 feet elevation gain, it is fairly a “walk in the park” compared to Thoreau’s “failed attempt” to scale the 5,267 ft. summit.

Leaving his camp mates behind one misty September morning destined for something greater than his usual "pastoral ramble", Thoreau set off on what can only be described as the Mother of All Bushwhacks, forging head-strong up a treacherous boulder-choked defile sloping 45 degrees, “hemmed in by walls of rock” channeling a deafening torrent of dangerous water:

“ . . . a copious tide, over and amidst masses of bare rock, from the very clouds, as though a water-spout had just burst over the mountain.”

He soon found himself in a nearly inextricable predicament clambering on all fours across a “mass of course basket-work” – the tops of stunted ancient black spruce trees (“old as the flood . . . as if for centuries they had ceased growing upward against the bleak sky, the solid cold”) – with bears sleeping in their hollowed dens ten feet below! – prompting Thoreau’s admission that it was “certainly the most treacherous and porous country I ever travelled.”

That experience, combined with increasing cloud cover, was as far as he got in his “failed attempt” before deciding it best to about-face and head back down to meet up with his camp mates. Unsuccessful, thwarted, stymied all describe his attempt to bag the summit . . . but failed is not a word I would use.

Undaunted, and doubly determined, the next morning he and his mates headed back up the granite falls and chose a route toward a higher peak where he eventually lost sight of them and so continued on his own, over gigantic loose rocks – “the raw materials of a planet dropped from an unseen quarry” – but still he was denied the glorious bare rock summit, concealed by mist from the “verdant plains and valleys of earth.”

The closest Thoreau got was attaining a cloud-blasted ridge five miles long, “a thousand acres of tableland” possibly just a few hundred feet short of the summit, before realizing the futility of his puny human endeavor against the “Vast, Titanic, inhuman Nature” where:

_katahdin%20from%2010000%20feet%20up.jpg)

“ . . . it is a slight insult to the gods to climb and pry into their secrets . . . only daring and insolent men, perchance, go there.”

Thoreau had met his match in the raw power of nature he confronted on a rocky precipice drowned in mist and clouds, and he was compelled to descend and admit defeat. He took solace in a view of the country west and south for a hundred miles of “immeasurable forest” and sun-struck reflections of a patchwork of lakes like a “mirror broken into a thousand fragments” – a view, he conceded, that was “as good as that from the peak.”

“Perhaps I most fully realized that this was primeval, untamed, and forever untameable, or whatever else men call it, while coming down this part of the mountain.”

And, where a wrong turn can lead you astray down a narrow, muddy, rutted path or on an endless loop chasing your tail not knowing where you are because your GPS no longer works and you’ve all but forgotten how to read a map or navigate instinctually like Joe Polis.

In remoter areas of the country, designated Dark Sky Preserves have been established where light pollution is kept at bay, not having yet despoiled the pristine darkness of a primitive night sky. We are in one such place, the 87,563 acre Katadhin Woods and Water Monument within Baxter State Park.

Where Thoreau and his mates, gathered around the warmth, comfort and safety of a fire, observed the glorious "deep field" of the firmament above, and “with the moon and stars shining in our faces, our conversation naturally turned upon astronomy.”

What would Thoreau think today of light pollution, a concept probably not nascent in his consciousness. Being a modern-day baleful nuisance, light pollution is a consequence of excessive and unnecessary artificial light sources which mess with species' circadian rhythms, reek eco-systemic havoc, disrupt natural cycles, waste energy, and mar aesthetic enjoyment of the natural world.

Next morning breaks clear and beautiful, and it’s time for a leisurely drive on the narrow, winding 44-mile Nesowadnehunk Tote Road – otherwise known as Baxter State Park Scenic Drive – stopping for views and hikes and detours to pick wild blueberries in a field with two little girls as though in a fairy tale. Thoreau may have picked berries from these ancestral bushes, and noted they were quite "delicious with their smart and spicy taste."

Toward late afternoon we arrive at Katahdin Lake for a brief spell to enjoy the sights and kick back in the sun, gazing at the pristine mountain backdrop of the azure lake, enjoying relative serenity and solitude for such a popular destination.

The tame visage of the lake is inviting and so we inch our way into the crisp, clear refreshing embrace of water. A pair of frogs hip-hop about and across a small cove lined with fir trees a Bald Eagle swoops down onto a giant nest constructed of carefully arranged sticks. We luxuriate in the lake’s embrace for most of the next hour, dreamily lost in thoughtless reverie on the precipice of heaven's doorstep.

Maine is a land of granite peaks, impenetrable marshes and bogs, inviting watery splendor and sylvan wonders, teeming with wild creatures, rarely seen, except for maybe moose and white-tailed deer, but if lucky, you might spot a fox, marten, fisher, weasel, bobcat, coyote, or catch the tail-end of a black bear rustling through the forest.

And don't forget your binoculars to spot many species of perching and shore birds seen seasonally and year-round. I spot a few pretty birds I have no idea of, and still don't.

.jpg)

Aboljacarmegus (Smooth-ledge Falls and Dead Water)

Apmoojenegamook (lake that is crossed)

Mattawamkeag (place where two rivers meet)

Passadumkeag (water falls into the Penobscot above the falls)

Piscataquis (branch of a river)

Umbazookskus (Much-meadow River)

Wassataquoik (East Branch Salmon River).

His appendix also included “Quadrupeds” spotted (not many); “Outfit for an Excursion” of twelve days’ time which mentioned the necessity of hiring an Indian guide for a buck fifty a day and change for use of his canoe; and “A List of Indian Words” many from translations according to his Penobscot guide, Joe Polis.

Maine is a biodiverse wonderland where a weary soul can enjoy solace and respite from the hectic pace of modern times, in peaceful surroundings where perchance it is possible to experience the magic and mystery of a primeval forest, refresh the senses, and tap into the vital and mystical energies of spirits past and present, human and animal, of the “boundless forests, and lakes, and streams, gleaming in the sun.”

Thoreau regarded the Maine backwoods as "savage and awful, though beautiful." Throughout his travails and difficulties, and even in quiet moments fishing or tracking a moose with one of his guides, Joseph Attean (the last hereditary Chief of the Penobscot Nation and first to be elected Chief), Thoreau constantly grappled with his mortality, confronted his struggle to exist easily and freely, as did Attean and Polis, with “the presence of a force not bound to be kind to man.” (Obviously, he was talking about the white man.)

Such elemental forces of the “unhandselled globe” and of “Matter, vast, terrific” impacted Thoreau in a visceral way, forcing him to question Great Mysteries and re-evaluate his Transcendentalist world view in light of the contradictions embodied in his relationship to his Penobscot guides.

His experiences made him reassess his comfort level in primitive surroundings with so-called primitive people. To examine the awanoch's (his own) conflicting, limited notions of wilderness and the duality of nature/culture and primitive/civilized of which his Penobscot guides (who unbeknownst or unacknowledged directly by Thoreau were medicine men, shamans) exposed as false dichotomies through their actions and speech as a fatal flaw and weakness of awanoch.

Who is this man and where does he come from? Certainly, not of the "pure Nature" Thoreau professed to worship and try as he might, live by its credo of integration, non-separation or differentiation.

Ultimately, Thoreau could not hold up his conflicting ideas and notions. Again, Tom Lynch assessing Thoreau as a failed student of the wilderness and native way of life:

"For in spite of Polis's efforts to teach him differently,

Thoreau maintained a notion of wilderness that led him to remain more

alienated from the natural world and less at home there than he needed to

be and hence limited the richness of his experience."

Perhaps there is some truth in that assessment, but in no way does it diminish who Thoreau was, or relegate him to some second-rate thinker. It IS the mid-1800's and Thoreau IS just 30 years of age, after all, when the prevailing ideas, notions and available knowledge of the day was fairly limited.

.jpg)

And we DO also see a progression in Thoreau's evolution of ideas and thinking, his sense of place, however much he struggled with it all or could not shake his awanoch sense of superiority, or leanings toward his comfortable bias and preference for finally leaving the wilds and feeling a sense of "a relief to get back to our smooth, but varied landscape."

And yet he realized that:

“ . . . the poet must, from time to time, travel the logger’s path and the Indian’s trail, to drink at some new and more bracing fountain of the Muses, in the far recesses of the wilderness.”

"It was the opportunity to be ignorant that I improved. It suggested to me that there was something to be seen if one had eyes. It made a believer of me more than before. I believed that the woods were not tenantless, but choke-full of honest spirits as good as myself any day."

Perhaps Thoreau was prepared to give up his rustic life (more comfortable than the fiction evoked in his Walden Pond memoir), renounce the civilized world of Concord, Massachusetts in which squarely dwelt, and find a spiritual haven in Maine in his end days before he became too sick. On his deathbed in 1862, dying of tuberculosis at age 44, his final utterance was, “Now comes good sailing”, followed by two distinct words evoking deeply imprinted memories of the spirit of the Penobscot world: “Moose” and “Indian”.

Of its ancient mystery, its enduring majesty, its manifest bounty found in the “pure Nature” Thoreau exulted over, he also envisioned a second kind of life, and death:

"What a place to live, what a place to die and be buried in!”

Perhaps in his final delirious moments, Thoreau the Explorer was finding his way back, like a salmon from the sea to its inland spawning place, or like a bird migrating from one corner of the world to a specific nest 10,000 miles distant. Finding his way back in a fever dream to his beloved Maine woods, returning to:

“ . . . the fresh and natural surface

of the planet Earth,

as it was made forever and ever.”

.jpg) |

| Pen and ink drawing of Thoreau by Kevin Erwin (1971) |

End Note

One-on-One with Henry David Thoreau:

An Imagined Conversation

"To every man his own Thoreau!"

(Fanny Hardy Eckstorm)

Henry David Thoreau is best known for his intermittent sojourn of rustication on the quaint shores of Walden Pond, over the course of two remarkable years from July 4, 1845 to September 6, 1847.

During this seminal period – his personal "experiment of living" in self-reliance, seclusion, and creativity – he compiled the wisdom and insight of voluminous notes and scribblings, treatises and tracts, and poems and natural histories into his most famous work: Walden; or, Life in the Woods (1854).

This masterpiece and subsequent encomiums over the years have informed the academic, philosophical, and literary scrutiny of his life and work since his untimely death from tuberculosis in 1862.

The man and his writings have been lionized and glorified, dissected and argued over, and critiqued and analyzed; the layers of his psyche peeled back, and the depths of his soul plumbed, in valiant and conflicting efforts to determine who he really was; to understand his values, ideals, and philosophies; and to what extent he lived and represented them faithfully and truly.

Thoreau was and remains a famously complicated person whose legacy is fraught with contention regarding what he wrote and stood by. History remembers him variously as a writer of books, essays and journals; a poet; a libertarian; an anti-government revolutionary; a naturalist; and a self-reliant woodsman who turned his back on coarse society for his love of solitude and nature.

From early on, his contrary, acerbic takes on most everything ran afoul of society and the law, even, and as such, along with suspicions that his "experiment of living" was not particularly an immersion in self-sufficient isolation, he became an easy target of historical and biographical revisionism by critics out to recast his legacy and downgrade his hagiographic status to one not quite so exalted.

To his dissenters, he is a poseur and a fraud; merely a good nature writer.

Defrocking Thoreau is meant to set the record straight by re-examining his reputation, handed down through the ages, as gospel truth and common knowledge – a reputation in dispute as early as 1865 that he was anything but a competent woodsman and superb naturalist, philosopher for the ages, and environmental champion.

|

| Walden Pond, 1908 (Wiki Commons) |

With dagger pens sharpened, the deconstructionists set about reframing the icon of self-reliant living – not as a literary figure or historical personage to revere and emulate – but as someone whom they contend led a false existence, a make-belief life, conceived of contradiction and hypocrisy, a life far removed from the romantic notion of mythic nature hero in the popular imagination.

Numerous they are, and with zealous determination bordering on personal vendetta, it sometimes seems, critics and opponents of the Thoreauvian world view make their case by exposing alleged flaws and foibles, pointing out contradictions in thought and action, and unmasking presumed insincerity and moral side-stepping.

Often, this results in unnecessary beat-downs in a form less given to historical revisionism than to mean-spirited ad hominem attacks, if for no other reason than to "stick it to" legions of Thoreau admirers and show us how ridiculous and wrong-headed our assessment is of "Saint Thoreau" – whom a contemporary admirer, Bronson Alcott, once described as "the most sagacious and wonderful Worthy of his time, and a marvel to coming ones."

In my invented conversation with Thoreau, I give voice and credence to his imagined reactions to those who cannot let go of their narrow-minded illusions, fabrications and misconceptions. Thoreau, the poet, writer, philosopher and nature lover rises from the dead with free rein to defend himself and fire back at three prominent critics whose writings have unfairly tarnished his character and attempted to diminish his legacy.

Two of the fusty contrarians have long since perished, and one is among the living. Each of their critiques, often offensive and personalized, are subjected to the microscope (or magnifying glass) of Thoreau's perspicacity, wit and generous wisdom with an eye toward imagining how he might have considered their shabby treatment of him.

It is one thing to confuse personal shortcomings with literary legacy, else we lose sight of the richness of thought and character of a man far ahead of his time but confined to its dullness and drudgery.

While Thoreau wrote wide-ranging philosophical treatises, biting sarcasm, humorous asides, political discourse and criticism, and lengthy passages on social awareness and society's "too cheap" hokum and humdrum, he often bogged the reader down with formal, didactic, dry writing. He was at his supernal best and wittiest dishing up wise apothegms and observations about life and penning flowery descriptions, unequaled to this day, of the natural world.

Thoreau was distinctly a product of his staid time: a white, privileged, wealthy male who could not totally escape from the denigrating "noble savage" kind of thinking that has gotten him into trouble, though he came to realize in the end that romantic idealization and elevation of classical Western culture was ethnocentric bunkum. And yet at the same time, let the record show, Thoreau had no hatred in his heart; he was far from being antisemitic, racist, sexist or misogynist.

Just presumably misanthropic. Not toward a single individual (man), but to the mass of individuals (men) whom he deemed neither beneath him nor above, but merely "desperate". In later life, perhaps realizing he was terminally ill with just a few years left, he softened his stance toward his fellow brethren and discovered "an inexhaustible fund of good fellowship," according to Brooks Atkinson, the long-time, well-respected New York Times theater critic, renowned essayist, and author of Henry Thoreau, the Cosmic Yankee.

Contentious, presumptuous take-downs of revered figures are what revisionist critics do. They look through an alternate lens and poke holes in the fabric of a myth. They deflate the person, tear apart the legacy, and feel like they've added to the constructive dialogue, and rectified misconstrued points of view and falsified aspects of one's life.

They may occasionally hit the mark, but how easy it is to write about someone in a way that conforms to one's own particular viewpoints and pet theories, as though Thoreau is a lump of clay they can mold to their whims. Which is why I let Henry David Thoreau speak on his own behalf – he who knows himself, his motives, his innermost secret, desires and dreams, better than anyone.

To Thoreau's critics who have promulgated maligning views of the man, his life, his works, I ask: can we forgive him for the petty human transgressions he is accused of (misanthropy, arrogance, difficult to deal with in relations), and remember him for his everlasting accomplishments: as an independent thinker who expressed concepts far in advance of their time; as a poet-dreamer motivated by pure love; as a voice of compassion and reason in a world gone mad; as a loner outcast courageous enough to decry society's hypocrisy, foolishness and moral failings at the risk of being seen as a selfish, arrogant scold and doomsayer.

.jpg)

Atkinson's introduction to the Random House publication of Walden and Other Writings (1937) should be required reading for Thoreau debunkers and revisionists. He writes of the "genius of Concord" whose book is a treasure-trove of "clear, sinewy, fragrant writing."

More than a dry account of a life immersed in the woods, it is high and mighty literature, and endures as a time-honored vade mecum of knowledge, learning and wisdom against "the world's cowardly habits of living."

Thoreau's oeuvre embraces multi-dimensional subjects and styles, and is crafted with droll flair and a stream of consciousness style imbued by unbridled imagination, subtle wit, humor and irony, biting sarcasm, and a hefty dose of creative license. We are not to mistake his contradictions, inconsistencies and such for anything but purposeful, playful obfuscation. Get with it and get over it, he often seems to say. I'm just messing with your mind and shaking up your world view.

As a whole, his writing are irreducible to the narrow, sharply defined criticisms of cherry-picked anecdotes, assertions and so-called facts about his character. The elephant in the room, so to speak, of which we all bring our subjective interpretations to bear.

The writer David Quammen has written:

“The case of Henry Thoreau stands as proof for the whole notion of human inscrutability. This man told us more of himself than perhaps any other American writer, and still he remains beyond fathoming.”

Whatever one's perspective on Thoreau, the man, his life and writings, Atkinson reminds us to hold dear his truest and greatest legacy, that being his:

" . . . passion for wise and honorable living . . . he yearned to be as pure and innocent as the flowers in the field . . . "

In our wide-ranging one-on-one discussion, Thoreau lets down his hair and bares his soul, not so much to toot his own horn over his accomplishments and soaring genius, nor primarily to defend himself against the onslaught of mean and lowly take-downs (my job!); rather to clarify aspects, illuminate controversies, and wipe away the cobwebs of misunderstanding of a simple, complicated life shrouded in myth, contradiction and half-truths.

To set the record straight regarding the verifiable facts and substance of his grand "experiment of living."

To experience empathy and understanding – "to look through each other's eyes for an instant."

To enjoy the full transcript of our one-on-one conversation, visit:

|

| Ora and her pal, Henry |

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Throughout the Maine Backwoods essay and end note, I have referenced multiple sources, documents and links to inform as accurately as possible the historical and biographical veracity of the narrative. Errors in judgment or interpretation are solely my responsibility.To better understand and gain a clearer perspective on Penobscot prehistory and post-colonial periods of conflict, I relied on the following article:

(Ferland, Jacques. "Tribal Dissent or White Aggression?: Interpreting Penobscot Indian Dispossession Between 1808 and 1835." Maine

History 43, 2 (2007): 124-170. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol43/iss2/3)

To more fully understand the perspective of Thoreau from the viewpoint of non-native interpreters (academics, writers), and to gain an understanding of his evolving idea of indigenous peoples and his notions of place and sense of polarizing constructs of nature and wild, primitive and civilized, I made liberal use of the following:

To glean insights into the changing orthodox view of the 19th century giant of literature, I found the following articles helpful.