SOLVITUR AMBULANDO: Paean to the Joys of Hiking & Benefits of Being in Nature

"There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream

The earth, and every common sight

To me did seem

Apparelled in celestial light."

– William Wordsworth

In an unexpected moment, imagine discovering ineffable beauty in every common sight. When meadow, grove and stream all delight. When Nature's treasures jump out, hidden in plain sight.

When our heart and soul are set aright.

W. B. Yeats wrote:

" . . . imagine a world full of magic things, patiently waiting for our senses to grow sharper."

Henry David Thoreau reminded us of our sensory fallibilities in grasping what he called:

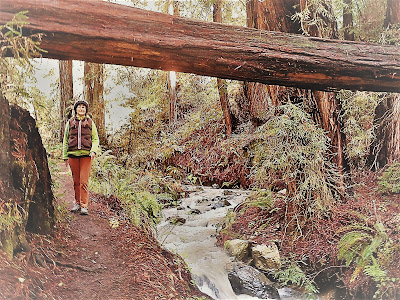

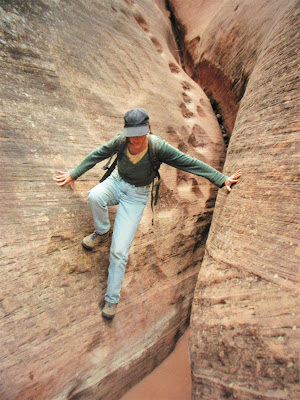

.jpg)

" . . . the subtile powers of Heaven and of Earth . . . [we] seek to perceive them, and we do not see them; we seek to hear them, and we do not hear them."

.jpg)

"Them" being, of course, all the marvelous things in a world full of magic!

The old doyens were speaking to our ability (or lack thereof) to attune to Nature's infinite wonders; to our capacity (or lack thereof) to swoon over her small miracles; to our receptiveness (or lack thereof) to be touched by her magic things.

Another way to understand our (dis)connection from Mother Earth, and the key to all sensory attuning, is what old-time zen naturalist John Burroughs referred to as:

" . . . the art of seeing [where] things escape us because the actors are small."

Long ago in another time, Burroughs exhorted us:

" . . . to look closely and steadily at nature . . . and take pleasure in the "minute things" about us."

Part mindfully and partly mindless, we make every effort to sharpen the senses. Joseph Wood Krutch wondered how else might we appreciate:

" . . . the daily and hourly miracle of the usually unnoticed beauty that is close at hand."

Way back when, though, John Muir knew the secret to shedding life's "carnal incrustations" built up over the citified years – psycho crud barnacled to the hull of our souls.

Muir's Remedio?

Hit the trail.

(In his case, with little more than a tin for tea and crust of bread for modest sustenance. Uber austere. But in the midst of such privations, Muir found that his carnal incrustations dissolved posthaste.)

Muir and his fellow scraggly-bearded, anchorite-living Transcendentalists, they knew the Secret of connecting with Nature. They possessed the Open Sesame mantra to unlocking the key to existential Earthly Paradise.

Their deep sought-after connection with Nature was (is) the most sure-fire method known to those so enamored to restore addled senses and reinstate long-lost, peaceful, easy feelings.

In short to make us the best of persons.

A promise, only Mother Nature, our Earth Mother, can fulfill.

A cure, only Earth Mother, our Mother Nature, can deliver.

Get your ass outside.

To the Great Outdoors.

Poor old boy. Surely, he knew the remedy to shed his psychic albatross of routine's dusty detritus and mold of mental stagnation.

Get your ass outside, Old Sport!

To the Great Outdoors, Man!

Posthaste!

And surely JWJ did so, penning his moving coda:

" . . . come to the peaceful wood / Here bathe your soul in silence / Deep in the quiet wood."

Deep in the quiet wood.

Where you do indeed find your better self.

Where crap does truly melt away.

Where carnal incrustations dissolve, life's oppressive weights are lightened, and society's rude demands made a bit more bearable.

Just by walking, all is solved!

SOLVITUR AMBULANDO!

WALKING SOLVES ALL!

In a thought-provoking essay on the subject, Arianna Huffington advises us:

" . . . to be wake to what’s happening around you," so that "your senses are heightened and you walk away with something office meetings rarely give you – a sense of joy. There is no end to the problems that can be solved by walking. It makes us healthier, it makes us fitter, it enhances every kind of cognitive performance, from creativity to planning and scheduling. Best of all, it reconnects us to ourselves."

Arianna nailed it and Henry knew exactly this truth long ago in his Walden World era.

Just a whippersnapper at barely thirty years of age, and already a world-class scholar, writer, poet, naturalist, and curmudgeon, the hermetic Thoreau made half-hearted attempts to engage society at large but was barely able to contain his contempt for "man and his affairs, church and state and school."

He was barely able to fool anybody with thinly disguised misanthropy, piled high with hefty doses of blistering social commentary thickly layered with biting political cynicism – "politics is the gizzard of society, full of grit and gravel."

Truthfully, it is not hard to imagine that Thoreau might well have gone insane were it not for his love of the great Out of Doors, his passion for his daily Nature fix, anticipation welling up in his heart for long walks and leisurely saunters where, he told us, "I would fain return to my senses."

But even in the unhurried world of 1848, dwelling in perhaps not quite so sylvan solitude on the post-idyllic shores of Walden Pond (already the ax men were hard at work leveling his cherished forest domain), ol' Hank could not manage to get enough of a good thing, that which he called Nature's "subtle magnetism" which "will direct us aright."

In his essay Walking, published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1862, the year he died, Thoreau laments his "occasional and transient forays only" to the "usual, quiet wood" where he'd set off without map or agenda for hours at a time (what else did he have to do?).

He kept detailed, minute notes (try reading his nearly indecipherable handwriting) on his observations of Nature's unfolding pageantry and majesty, ever contemptuous of his flabby, lazy compatriots – "the mechanics and shopkeepers" – those busy, industrious townsfolk who could care less about the wonders and magic of natural world, and who thought of him as an eccentric outlier.

As for what Thoreau thought of these "mass of men" who led lives of "quiet desperation", he opined: "They deserve some credit for not having all committed suicide long ago."

An anti-social anchorite who detested the dreaded routines of his "neighbors who confine themselves to shops and offices the whole day for weeks and months, aye, and years almost together," Thoreau took solace in Mother Nature's healing balm:

"I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits unless I spend four hours a day at least – and it is commonly more than that – sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements."

But there's the rub!

Worldly engagements and other reality entanglements, Thoreau had aplenty. With two years of self-tutelage under his belt studying Nature's infinitely variable minutiae, Thoreau emboldened his spirit with an inspired vision of the Transcendentalist world view, in vogue at the time.

In Ralph Waldo Emerson's immortal words, the Transcendentalists subscribed to a doctrine that:

" . . . believes in miracle, in the perpetual openness of the human mind to new influx of light and power; he believes in inspiration, and in ecstasy."

Say no more.

" . . . to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life."

Like some spiritual paragon (or exile) in the desert, or Native American vision quester, Thoreau was heaven-bent on sucking out "all the marrow of life," and drew immense hope and courage, and fortitude and faith, from his daily forays and immersions in Nature.

Qualities in demand in order to turn his back on his beloved "vast, savage, howling mother of ours, Nature, lying all around, with such beauty," and begin the long walk back to society, leaving behind his humble cabin abode in Walden Woods to front the bleak prospects of managing a family pencil manufacturing company.

The dreaded business!

Like John Muir, who returned from his wild peregrinations in the Sierra Nevada mountains to become a gentlemanly farmer in Martinez later in life, Thoreau also returned to decency, to normalcy and stability (as opposed to a Jeremiah Johnson Mountain Man icon), and attempted an honest go of things, even subscribing to the publication, Businessman's Assistant.

Go figure, he must have thought. But seriously, he despised the businessman and all his busy business, proclaiming it "an infinite bustle, nothing but work, work, work."

The dagger line he wrote in his essay, Life Without Principle sums up his anti-business attitude:

"I think that there is nothing, not even crime, more opposed to poetry, to philosophy, ay, to life itself, than this incessant business."

Makes you wonder if life's vagaries and contradictions ever haunted Muir and Thoreau, ever stirred up the old piss 'n vinegar in them, a late-in-life cri de coeur for their lost, irrepressibly restless souls, for a yearning for adventure once again, a deeper longing to witness a mountain sunset or lakeside sunrise, but now forever in the past.

A dream, an idyll, lived and suspended in eternity.

Muir lived a good life into the twentieth century, while Thoreau fell to the ravages of tuberculosis at the wise beyond his years age of forty-four in 1862. The final words issued from his lips: "Now comes good sailing." (Aye, matey!) Followed by "moose" and "Indian". (Say what?)

Makes you wonder if Thoreau was delirious, or finely tuned to the Infinite and Eternal Mystery at the moment of his passing?

Thoreau probably knew the expression Solvitur Ambulando. In the mid-nineteenth century, a time when people, even scientists, had nary an understanding of such matters, Thoreau presaged modern research into the physical and psychological benefits of walking, how walking physically changes our brains, rewires our neural circuitry, relieves depression, lowers anxiety levels, on and on and on – infinite healthy side-effects!

It's what keeps us living, keeps us breathing.

Walking in Nature!

Absorbing water's ionic energy!

Breathing in lungfuls of Tree Oxygen!

Japanese Nature Lovers know it and its benefits as:

FOREST BATHING

They're totally on to something.

It is true, just by walking, by being around water and trees and flowers and sky and earth.

.jpg)

We become the best persons.

We become One with Mother Nature.

Our True Nature.

Where body / mind / spirit infusions of high dose O-2 and blasts of the other Big O – Oxytocin – caress the senses into a heightened and sensual state of limbic-brained ecstasy.

In the bosom of the Great Mother – Mother Nature – we never had it so good.

“A vigorous five-mile walk will do more good for an unhappy but otherwise healthy adult than all the medicine and psychology in the world."

Nothing cheers the heart more than a vigorous walk in the woods. Nothing beats breathing in fresh air. What could be more liberating than sloughing off the day's malaise, as worries and cares melt away.

Walking and being in Nature!

The Secret to staying happy and young at heart, proclaimed herein – the Secret to staying sane! Walt Whitman affirmed that being in the open air, in touch with the earth, makes for the best persons.

How can you argue?

Time to get in touch with the Earth.

Time to do a little Earthing – a practice to connect on a deeper level with Nature by going barefoot.

As kids, we did it all the time. What happened, people?!?

Come on, lace up the boots and let's dive into some Earthy Earthing!

Hug a tree, jump in a lake, smell the savory bark of a tree, eat some dirt, get lost!

Feel life!

Suck out its marrow!

Let's take a look, seek out beauty, stumble upon tiny treasures, every step of the way along our simple journey.

Our journey of simple miracles Ansel Adams intuited as:

" . . . incomprehensibly beautiful . . . an endless prospect of magic and wonder."

Certainly, too, we can all fain return to our senses and be directed aright, in our daily Ambulandos, Solvituring it all.

And great Yukon poet Robert Service really hit emotional pay dirt with his timeless taunt:

🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎

"What?

You're tired and broken and beaten?

Why, you're rich, you've got the earth!"

🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎

WHY I WALK IN THE CALMING BOSOM

OF MOTHER NATURE:

I WALK to find solace and peace — a fools’-proof way for monkey mind to cease.

I WALK to see so many wonderful sights — and sleep refreshed come the cozy nights.

I WALK to roam and explore the back ‘o beyond — even if it’s just a gentle little turtle pond.

I WALK for fun, for exercise and thrills — nothing better for you than chargin’ up those hills.

I WALK to strip bare the longings of my soul — reflecting about it under a giant redwood or upon a little knoll.

I WALK to experience the deep cleanse of forest bathing — to emerge with a light heart absent of craving.

I WALK to immerse myself in nature’s sweet embrace — discovering secrets along the way of truth and grace.

I WALK to leave the madding world behind — no hint of it, nothing to remind.

I WALK to WALK— to huff, puff and sweat — to pay down all that karmic debt.

I WALK to restore my sanity — and to rid myself of ego and vanity.

🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎 🌎