BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA: Congregations, Flocks, Charms & Other Intriguing Manifestations of Birds Living in Pockets of Urban Wildness

Birds! Birds! Birds!

A Charm of Finches, a Host of Sparrows, a Party of Jays, a Murder of Crows, an Unkindness of Ravens. What next, a Parliament of Owls?

.jpg)

Birds are highly evolved, ethereal beings and I enjoy watching them do their avian thing in the 108-year old Interior Live Oak gracing our side yard. We live in an historic apartment building situated in a primo North Berkeley neighborhood just a couple of blocks from where the first rises begin in the Berkeley Hills, a funky 17-unit building that looks like a stately Victorian married the Alamo.

Back in the sixties, it was an acid dropping scene of ongoing bacchanalia, a Windowpane into a freaky world, a Mr. Natural crash pad, a Love Saves sanctuary of bliss, a Purple Haze haven of orgiastic parties with a gallimaufry of legendary Berzerkeley characters coming and going through the psychedelic revolving door.

Even Alice Waters lived in our very apartment back in the 60's. And, we were informed, several years ago, these very premises were spiritually graced with a visit by Vietnamese Buddhist monk, peace activist and writer, Thich Nhat Hanh, who stayed here for several days, in our very own ‘umble apartment, right next to the 108-year old Oak tree that the birds (and many other appreciative critters) love so much.

Before that, it was some rowdy boardinghouse, back in the vanquished day of horsemen and iron horses, when the old Berkeley Branch Railroad (a line of the Central Pacific) ran a few blocks away. Allen Ginsberg once lived in a cottage just up the street.

And way before any of this, indigenous Ohlone Peoples – Berkeley’s first natives – gathered not far from here at volcanic outcrops of rhyolite to grind acorns into mush in foot deep cylindrical mortar holes for many delicious and nutritious treats to sustain their journey through life.

Berkeley is blessed with wonderland parks, home to spruce and redwood, bay, alder, big leaf maple, sycamore, madrone and manzanita, plus many oak varieties. Neighborhoods in Berkeley are lush and tree rich, perfect bio-sentinels to attract urban tree loving creatures on the prowl, such as possums, squirrels and raccoons.

Deer browse and nibble in the simulacrum of a forest in our back yard. Free-flowing Codornices Creek is just one yard over. I’ve seen wild turkeys strutting nonchalantly down our street on deserted early mornings, and – a spectacular appearance ending in tragedy – a mountain lion was shot and killed by the Berkeley Police right down the street a couple of years ago.

Birds are a natural and integral part of the eco-equation, and the fascinating, flitting, fugacious, freedom-loving feathered friends of the firmament come in droves, frequenting the 108-year old oak tree to engorge on bugs, larvae, grubs and acorn nuts.

Sprouting from a tiny seedling acorn of the valley clan of arboreal wonders, our venerable Quercus wislizeni grows in a gnarled network of tentacled branches, elephant leg in girth, rising 108 feet to form a dense, nutrition rich canopy, a woody and leafy world unto its own.

From where I stand on my porch, binoculars affixed to eyes in an oft-futile effort to locate and identify the many birds that come to roost, peck around, and bounce from bough to branch, it seems a most unlikely place to watch for birds.

.jpg)

Yet this mature, robust tree draws in like a magnet many avian wayfarers in search of abundant sustenance and tasty victuals – delicious pickings from the underside of rotting strips of bark.

As in the case of the stunning adult female Downy’s (or was she a Nuttalls?) Woodpecker I spotted last week, a technique she has down pat resulting in a notable absence of the repetitive rat-a-tat-tat knocking associated with Picoides nuttalli and others of her ilk. The experience almost seems oxymoronic, watching a Woodpecker engage in silent work.

In the past several weeks, during a spell of some La Niña inspired superb Mediterranean weather, I must admit, I have spotted more species of birds from the vantage of my porch in one sitting than in far wilder places up in the hills.

Lately, I’ve taken a greater interest in connecting with our resident and migratory bird population in the big old accommodating oak. Of an early morning, with the tree situated nearly within reach outside the bedroom window, I awaken to a clamor of sweet pitched melodies from several different, completely anonymous birds.

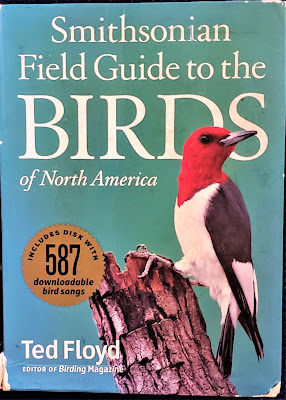

Who are these little winged royalty announcing their joyful presence at my crepuscular window, I want to know. It’s the same ambition that drives any crazed bird lover (or bird lover crazy), such as Ted Floyd, author of Smithsonian Field Guide to the BIRDS of North America, who poses the abiding question: “What is the name of that bird?”

He goes on to make a case for the importance of identifying / naming / classifying:

“A name is a tool for organizing our thoughts, for making sense of the world around us. Knowing the name of something makes it more important. Giving a name to something immediately triggers a cavalcade of questions, of discovery, and of wonder.”

And yet it’s hard to disagree with Walt Whitman, who famously counseled:

“You must not know too much or be too precise or scientific about birds and trees and flowers and watercraft; a certain free-margin, and even vagueness – ignorance, credulity – helps your enjoyment of these things.”

I’m divided on the issue. I’ve always been a rank amateur when it comes to knowing the Linnaean underpinnings and taxonomic fine points of flora and fauna, hence my broadly aesthetic and spiritual (as opposed to scientific minded) approach to my appreciation and understanding of plants and animals and natural history in general.

Perhaps characterized as the “Gambolin’ Man” world view?

I only hope that the discovery and wonder that Floyd writes of inspires a deep (organic) understanding and respect of our relationship to birds, all creatures and to the Earth, and does not, at the same time, drain too much of the mystery and magic out of birds’ fabulous existence.

The birds attracted to the big Oak tree are unpredictable and, like most of nature’s comings and goings, usually go unnoticed – their “here one day gone the next” proclivities keep you guessing and on the constant look out. Migratory patterns may or may not matter.

Birds, occasionally delicate little sailors, get blown off course and / or food and climate trends instinctually create revised flight patterns for many long distance winged trekkers.

And yet, ecce arborus, behold this Oak tree that has been on the scene for 108 years and for another century or more will likely continue to be a bonanza of shelter, a cornucopia of food, and a smorgasbord of insect delights for many different avian species, such as, for example, the sweetest little peeper you ever saw, the handsome Chestnut-backed Chickadee.

This skittish, acrobatic little fellow often seen hanging upside down, clinging with the tiniest of talons to a shred of a branch, dangling ever so momentarily to pick clean the underside of a moldering leaf.

Around 925 of 10,000 known bird species have been noted in the U.S. and Canada, almost four times fewer the number found in South America and half as many as are found in Australia. Still, 925 is a lot of species, and I doubt if any birder on the planet has seen all 925 of ‘em.

Maybe 200 live in or visit the Berkeley area? I suppose if you were determined and lucky enough, you might be able to spot 500 or 600 in a lifetime of traveling from the deserts of the Southwest USA to the tundra of Northern Canada and all points in between. I’ll be lucky and content enough to spot 150.

Bonus side note! Just today I added to my Life List a Varied Thrush, a beautiful orange / yellow/ bluish member of the Turdidae family spotted in Tilden Park in a dense entanglement of trees, brush and vines near the Botanical Garden.

I was zooming by on my bike when I noticed at the last second a group of intent observers with hi-tech binoculars and expensive camera equipment. I knew it was a serious sighting. I told the group, you made my day!

Birds are profoundly fascinating and are “among the most conspicuous forms of life on earth” writes Floyd in his important book; they are profusely dispersed and insanely well-adapted around the planet and are undisputed master survival strategists.

On the scene for perhaps 150 million years, birds thrive by their ability to exploit every available niche imaginable (sound like anyone else you know?), from the harshness of arctic and desert climes to the unending riches and variation of rainforests, to a plethora of microhabitats in between.

Forests and woodlands, prairies and meadows, deserts and shrublands, alpine and arctic tundra, wetland and aquatic, swamp forests and boreal bogs, rivers, lakes and ponds, fresh and salt water marshes, ocean beaches . . . and everywhere humans dwell.

The bounty of our urban neighborhood trees brings us a beautiful dissimulation of bird, birds, and more birds!

Birders, you see, are serious fanatics. There’s a ton of top quality bird related websites. People travel to the far ends of places like Arkansas and Siberia to spot unique birds. Birders go to conventions for bragging rights to life sightings.

As scientific research (at the molecular level) continues to pry open the mysteries of genetic (“racial”) variability among songbirds, more and more species will “split” and become two, sometimes three, species – upping the birders’ life list number – while, of course the reverse can happen, too, where two species are “lumped” and become one, thus diminishing the birder’s life list tally.

The super-odd thing about it is, why are some people bird-crazy and others just plain couldn’t give a Gnatcatcher’s ass? Now, I'm no bird expert, just a hobbyist, so no discourses on complex alternate molting strategies or kleptoparasitism, but it is fun to speculate about them while learning astonishing things in the process.

Until I brought a couple of jocose birds into my immediate purlieus with the aid of binoculars, these tiny creations of hundreds of millions of years of evolutionary design had heretofore been nonexistent to me as individuals; they were aggregated in my mind as an abstraction – merely the “birds”, nameless, unknown, featureless entities.

But get to know them, and their personalities jump out. And you want to get to know them better. No wonder bird lovers are so fanatic and passionate about their subjects, because birds are expressions of freedom and symbols of vitality, merry songmakers without a worry, care or regret. I love the way Izaak Walton characterized them as:

“ . . . little nimble musicians of the air, that warble forth their curious ditties, with which nature hath furnished them to the shame of art.”

One day, in the woods near by boyhood home in Oxford, Indiana, at a place called (yes) Slaughter’s Pond, I shot a little Sparrow or some such bird, and down, down, down, the mangled bird fluttered to my feet, in writhing agony, not yet fully dead.

Even at that tender age, I was stricken with a dreaded sense of having violated a major karmic rule – I killed a creature wantonly. Heart-broken and grievous, I knelt down to cradle her in my hands, but she died.

Birding, I’ve found, is a hobby requiring patience; no use getting fidgety or anxious or bored. You’ve just simply got to want to spot the colorful little firecrackers! And let me clue you in on a secret – spotting them is difficult, requires time and skill, like finding chanterelle mushrooms camouflaged in the loamy detritus of an oak forest floor.

On the other hand, identifying and knowing birds should be as simple as James Whitcomb Riley’s commonsensical declaration:

“When I see a bird that walks like a duck and swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, I call that bird a duck.”

I’ve found that birding brings a great sense of connection and is an enjoyable way to add dimension and spice to a nature (or porch!) outing. But sometimes there just aren’t any birds reporting. And so it’s easy to get distracted or lose interest.

The process is akin to filtering water at the river – no sense in trying to strong arm the precious stuff through the mechanism into the bottle to get it done quicker. It’s a sacred thing – breathe, give thanks, and take it one steady pump at a time. Same goes with the art of observing birds in their natural habitat.

With patience comes a sweet reward, an intimate glimpse of, say, a Common Yellow-throated Warbler. This dancing, preening specimen is so friggin’ common I didn’t even recognize the adult female first time I espied her. What – who? – am I looking at, I kept saying, putting down the binoculars and running into the house to consult the omniscient field guide.

Sounds ingenuous and overly earnest, I know, but I’m just enthralled with making the acquaintance. Thoreau expressed a similar preference thusly:

“I once had a sparrow alight upon my shoulder for a moment, while I was hoeing in a village garden, and I felt that I was more distinguished by that circumstance that I should have been by any epaulet I could have worn.”

I’m still hoping to spot her dolled up companion, the adult male, a flamboyantly emblazoned character donning a black Zorro mask and a brilliant yellow throat and underbelly.

How can such a tiny, insignificant creature – I’m the only person on the face of the Earth aware of this particular bird’s existence – be so achingly beautiful? The name may be common, but a sighting and positive identification is truly exotic.

Often these birds seem fragile, neurotic, frantic, with barely a motionless moment to rest or preen. All the constant nibbling, pecking, hopping, bobbing, and flitting about makes it difficult to home in on them. You might be lucky to get a tenth of a second appearance. Try identifying that!

When the diminutive specimens are viewed through binoculars, their bulk is magnified significantly; but when viewed up close, it’s astonishing how tiny they are! Like the time my little friend, the Townsend’s Warbler, landed in a bush right outside my window, surprising me with her Lilliputian frame.

.jpg)

Checking in at ten grams and five inches on average, this chic little bird is a regular patron of the big 108-year old Oak. Not much to twirp about, but he’s become a constant companion and a beautiful one at that, almost like my little pet when I see him decked out in his feathery duds, with the dark cheek patch of nifty black radiating out from his eyes surrounded by yellow on the sides, a flitty chap on the constant qui vive.

The littler the bird, it seems, the more frenetically paced it is, like wound-up dynamos, spunky engines of aerodynamic superiority and survival mastery, doing their thing in the 108-year old oak. The ultimate legacy of the lumbering dinosaurs may be these very birds, descended from chicken-size therapods who didn’t die out at all, but morphed into flight masters of the empyrean realms giving them a superior evolutionary competitive edge.

One day a pair of Cedar Waxwings – who? huh? – took up residence for a day in the dense foliage of our neighbor’s unidentified red-berry producing tree; seeing them has to count as a special sighting. These rather unusual looking birds are normally seen in flocks, not just two lovebirds by themselves.

So seeing just the two of them for the first time ever caught me off guard, especially since their plumage is of a more exotic nature and I couldn’t be sure I wasn’t hallucinating a tropical bird or something. How is it that I had never heard of, much less noticed, these Code 1 birds (commonly sighted) in my entire life?

Because if I had seen one, I surely would have marveled at the distinctive red stripe at the base of the tail, and appreciated as though from the palette of an old master, the subtle splotch of yellow where God spilled a bit of paint on the lower wing, and would have been taken in and charmed by the little crest of a wave of feathers in her head.

How, I ask again out of sheer disingenuous implausibility, had I missed the Cedar Waxwing in my lifetime of ??? – well, never being a serious birder . . .

Sadly, songbirds are taking a beating, have been for a long time, at the hands (paws and claws, rather) of domestic and feral cats; by their own kind, the maligned Cowbird being a notorious example of aggressive behavior displacing songbirds from their nests and habitats (the bird equivalent of Manifest Destiny?); and sadly but not surprisingly by destructive human activity, including mass poisoning by power plants.

In a report just released by the Biodiversity Research Institute they’re finding, according to a New York Times report:

“ . . . dangerously high levels of mercury in several Northeastern bird species, including rusty blackbirds, saltmarsh sparrows and wood thrushes.”

Sadly, this is causing reproductive and other health and well-being problems that threaten their existence as a species. And that’s just a few species at risk.

Oddly, Audubon does not mention a thing about mercury poisoning caused by coal burning power plants on its website. What does it mean not to be able to hit a high note anymore? How can a marginally competitive bird avoid the risk of extinction if x-percentage of surviving hatchlings continues to plummet?

These and other pressing questions plague me, as they did the doyen of birders, Roger Tory Peterson, who wrote that birds are:

“ . . . sensitive indicators of the environment, a sort of ‘ecological litmus paper’ and hence more meaningful than just chickadees and cardinals to brighten the suburban garden, grouse and ducks to fill the sportsman’s bag, or rare warblers and shorebirds to be ticked off on the birder’s checklist. The observation of birds leads inevitably to environmental awareness.”

Alas, with all that freedom comes a heavy price – extinction.

So far, I’ve compiled a list of around 40 birds (!) who’ve come to visit the 108-year old Oak tree in our yard. Dramatis ornithonae include (in random appearances):

Chestnut-backed Chickadee. Dark-eyed and Slate Junco (immature female). Bushtit. Lincoln’s Sparrow. Common Pigeon. Morning Dove. American Crow. Raven. Townsend’s Warbler. White-crowned Sparrow. Ruby-crowned Kinglet. Bewick's Wren. Lesser Goldfinch. American Goldfinch. Oak Titmouse.

Yellow Warbler (immature female). Orange-crowned Warbler, Unidentified Warbler (w/ tiny patches of yellow on underwing, otherwise drab color). Vireo of some sort. American Robin. California Towhee. Anna’s and Rufous Hummingbird. Common Yellowthroat Warbler (adult female). House Finch. Purple Finch (adult male and female). Northern Mockingbird.

Yellow-rumped Warbler (adult male). Ladderback and Nuttall’s Woodpeckers (adult female). Steller’s Jay. Blue Jay. Sharp-shinned (possibly Cooper's) Hawk. Pacific-slope Flycatcher (with fledglings). Brown Creeper. Black-headed Grosbeak. Wood Thrush.

.jpg)

I’m always enchanted by each and every one of them, even the “prosaic” ones. How about the "pedestrian" ones, such as a passel of Pigeons I witnessed clucking up and down the sidewalk the other day!

For the minute an unindividualized bird become familiar to you, you will never regard it again with detached disinterest – lo, Floyd is right! Wonder and discovery does spur excited inquiry into other matters of their nature!

Like birds' mating habits and rituals, their lifespans, where do they go in the dead of night, where are their hidden nests and shelters, what are their survival strategies against competitors, how do they make a living, and do they do the things they do for fun and enjoyment?

The magic and mystery will always remain, because they are eternally unknowable, all their unseen secrets, infinite, hidden . . . And so let me better understand Corvine family behavior – the amazingly intelligent Crows, Ravens and Jays.

The Corvine Family: a Top Ten Intelligent Species!

With more knowledge, more sightings, you suddenly want to know everything about birds, because ironically, they are the Canaries in the coalmine, or coal power plant in this case, harbingers of our own future; we are inextricably linked to birds; our welfare is their welfare, or vice versa.

An eco-visionary ahead of his time, Roger Tory Peterson foresaw the interconnectedness of the fabric of life, the fragile bond that holds it together, the fatal consequences of our continued misguided acts in the mirror of birds held up to humans’ image:

“Alas, we are linked with them: Birds are indicators of the environment. If they are in trouble, we know we'll soon be in trouble.”

And so you yearn to glean an understanding of the complete natural history of all the birds you’ve met so far. A beautiful poem by Mark Hastings – The Dissimulation of Birds – contains the line, "birds have so many gifts to be envied . . ."

Maybe it has to do with a certain species' self-interest – to save ourselves and the Earth.

Deep down, we all truly wish to grasp in deep appreciate what Emily Dickinson meant when she penned:

“I hope you love birds too. It is economical. It saves going to heaven.”

Enjoy a walkabout with Gambolin' Man in two of Berkeley's charming, bird-rich parks:

Read more about Gambolin' Man's premier birding experiences at Live Oak Park, Codornices Park, & at many other parks in the Berkeley Hills, flats & marshlands: