POINT REYES, SINBAD CREEK & STEEP RAVINE: Three Fun-Filled Days Hiking, Biking, Birding & Whale Watching in Classic California Style

Today we’re in luck. The normally fog-shrouded Point Reyes Headlands are thankfully free of the impenetrable gloom of ocean-scented brume.

We're leisurely taking in the vastness of the uncontainable ocean when suddenly, out of the blue, we spot a large moving body torpedoing through the great water.

THAR SHE BLOWS!

A small pod of juvenile Pacific gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) has decided to extend their stay for a couple of months en route on their northerly migration from the calving lagoons of Baja California back to the nutrient rich feeding grounds of Alaska.

This doesn’t happen often, according to the ranger on duty at the Lighthouse where we are watching a live version of the Nature Channel.

Even though the whales are far below us, and visible for only fleeting stretches, watching them maneuver has a transfixing effect on us.

For those who have never witnessed whales in their natural habitat, a raw and powerful experience, one that begs for a closer vantage point and a deeper connection to an iconic ocean mammal symbolizing intelligence and love and epitomizing the highest form of grace.

But the sad reality is that these anthropomorphic virtues have not always led to respect and care, but instead have led humans to exploit the gentle creatures and slaughter them to near extinction.

Fortunately, over the past decades, environmental awareness has done a lot to “save the whales” – and E. robustus has made quite a rebound – but in the face of worldwide condemnation and scorn, some countries persist to this day needlessly hunting and killing whales in the name of “cultural tradition” and “historical rights”.

Can't we all just get along?

Cetacean (and LSD) researcher John C. Lilly envisioned a time when all killing of whales and dolphins would cease:

" . . . not from a law being passed, but from each human understanding innately that these are ancient, sentient earth residents, with tremendous intelligence and enormous life force. Not someone to kill, but someone to learn from."

Given the charismatic behemoths’ amazing endurance for swimming up to 10,000 miles a year, sure, why not stop a while, take a load off their fins, and enjoy an unprecedented buffet off the coast of the Point Reyes Headlands.

After all, conditions for feeding are perfect for so late in the year for these adaptive bottom scroungers, and they’re old enough to be left behind by their parents, by now somewhere in the Bering Strait.

What a sight to behold the Jovian creatures in their natural habitat, surfacing for a few moments to breath and spout, before lunging in exquisite ballerina-like movements (so fluid for being school bus sized), and then heading back down to the mucky depths 200 ft. below to scoop up crustaceans, krill and small schooling fish that they suction through their gigantic maws.

In gargantuan retractions to expose an unimaginably large 2500 lb. tongues, they filter out the mud through their baleen plates, leaving their tasty comestibles – and then right back up again to the surface, blow-holing, breathing, lunging, snorting, and back down again.

The search for ever more mouthfuls of food – they eat up to 65 tons of sea critters in one year – is a constant activity, and yet they, like all Cetaceans, surely make time for fun and frivolity.

We watch gleefully for nearly an hour as several of the once-near extinct whales put on a show for just a few of us lucky observers. Not being able to capture a decent shot of Moby with my little point and click camera, though, is really irritating and exposes me for the wildlife photographer fraud and rank amateur that I am.

The typical Bay Area July and August days, characterized by spates of cool weather and enveloping fog, with occasional spells of heat and smog, are finally behind us, consigned to the memory of a summer that barely was. Thankfully, the gentle month of October has arrived.

Although fraught with potential fire danger, should those Santa Ana winds decide to pick up and inspire arsonists to commit dastardly deeds, or some smoker carelessly flick an ember into tinderbox grasses, the tenth month is one of my favorite times of the year.

It arrives fresh with the promise of splendid Indian Summer days still long enough to enjoy colorful fall weather into balmy evenings and setting the stage for unspoiled views of pristine coastline and scintillating expanses of deep blue ocean.

This past week, sure enough, it all comes together during three fun-filled days out 'n about gamboling in the Bay Area’s numerous parkland playgrounds.

Hey, who needs aspens turning crimson and gold in the High Sierra or the coast of Mendo’s postcard beauty or wine country in San Luis Obispo when you’ve got full days on the home front waiting for you.

Many adventures await, whether road biking, whale watching and beach strolling at Point Reyes National Seashore; mountain biking in a remote canyon at Pleasanton Ridge Regional Park; and an invigorating hike up to the high forests of Steep Ravine at Mount Tamalpais State Park.

Where you wrap up the day down on the wild, rocky shores south of Stinson Beach for a late afternoon of watching, in spellbound wonder, the ever-changing but constant sea rolling and unfolding around us.

The scenic wonders and natural treasures of Point Reyes National Seashore are well documented and have provided plenty of literary and photographic grist for this blog over the past couple of years.

I’ve posted several accounts describing many alluring places on the peninsula – the 30 ft. drop-dead gorgeous waterfall over a rugged cliff face at Alamere Beach; fantastical geology and the lonesome castaway sensation of remote isolation at Sculptured Beach; the arduous Bear Valley hike through hill and dale to fabulous Arch Rock.

And the scenic extravaganza and wildlife bonanza entailed in the ten mile out 'n back hike from Pierce Point Ranch to Land's End at Tomales Point, taking in wild and wind-swept McClure’s Beach as well.

Although it doesn't seem possible, this is the first-time visiting Drake's Beach, as well as the first time checking out the famous Lighthouse station. Writing in an earlier post:

There’s no place like Point Reyes National Seashore. Lucky for me, I can return on any given day for another adventure, another surprise.

Which, no surprise, is exactly what Drake’s Bay and the Lighthouse provide.

But let’s not mistake this as a day filled with heart-pounding adventure or adrenaline racing activity. Rather, it's a day to just enjoy ourselves, get the blood flowing and heart pumping a bit, but no hurries, no rushing about, just try to be in the moment and take it all in.

The day's mild-mannered exploits begin with a drive south on Sir Francis Drake Boulevard – Lighthouse Road – passing by several historic (and stinky) dairy farms dotting the rolling landscape, not green like Wisconsin's – at least not until our rainy season – but brown and sere; one might say drab, even.

Which makes it difficult to spot the camouflaged raptors or appreciate the land's subtler charms. On first glance, this landscape is not dramatic, nor appealing, nor striking, nor anything but pedestrian in scope.

No tall mountains or even respectful sized hills grace the horizon, merely a few rises and hillocks; no rocky tors or outcrops of boulders break up the monotony to add dimension and texture to the small undulations of earth.

No wide-open views of the sea; no trees, glorious trees, to speak of in this prairie-like expanse of agriculturally commissioned land mixed with wide open . . .

WILDERNESS!

THE PRESERVATION OF THE WORLD!

For on closer inspection, this landscape pulses with life and vibrancy and earthy vigor.

By accepting it for what it is and letting go of preconceived expectations and unfair comparisons, one comes to realize that wilderness, sacred land, can be simple and humble, too, and is everywhere, anywhere, where there is a sense of the natural uninterrupted rhythm of life.

This preserved ecosystem is a remnant habitat connecting parcels of land to one another, constituting a patchwork of critical wildlife habitat that may have forever been lost to the ravages of development and agricultural industrialization, were it not for the spirit of wilderness preservation so ingrained in the American heart and ethos.

In a lackluster land bereft of blockbuster natural features – until you get to the coast! – one finds a truly wild place saved by one stroke of John F. Kennedy' s pen in 1962 – where packs of coyotes roam, megafauna graze, lonesome big cats prowl, families of deer forage, and, who knows, a sneaky bear or two could be on the loose.

A preponderance of raptor species, as well as multiple dozens of flocking and perching birds, and more snakes than you can count, find this seemingly nondescript place to be a perfect habitat for their survival needs.

Who am I to say – because it lacks Yosemite's grandeur or Tilden Park's modest majesty – that it is of no aesthetic or ecologic consequence?

Look around – this is a biosphere of outstanding proportions! (Besides, there is plenty of hill and forest country contained within Point Reyes National Seashore.)

Happy to be out of the car and surrounded by wild pasture – Keats' "fair and open face of heaven" – we park off the side of the road, set up the bikes, and zoom off on a rollicking blast down to Drake's Beach.

Talk about unbridled bliss screaming down the eight percent grade for a quarter mile with the whole ocean panorama stretching before us – a shimmering blue vision of delight at the continent’s edge.

The parking lot is nearly empty; just a handful of people are here, quite a contrast from the busloads of school kids, Euro-trampers, and tourists from the Midwest who pack the place, no doubt, during the “season”.

We secure our bikes in the outdoor patio of the Visitor's Center, where dioramas lay out the history of Drake's Bay, informing us of the various noble and heroic deeds of Sir Francis, the English courtier, admiral – and let's face it – pirate, looter and bellicose swashbuckler.

All, of course, done in the good name of the English Crown, which was desperately fighting the rival Spanish imperialists, pesky and greedy bastards that they were. The whole lot of 'em were, no doubt, from the Miwok's perspective , the peaceful natives inhabiting the coastal area for millennia.

At first, they befriended the weird-looking picaroons, but certainly later regretted their natural amity. Considered the good guys, I suppose, Drake and his motley crew ended up kicking the Spaniards' butts in campaign after campaign under Good Queen Bess' (Elizabeth I) auspices.

En route to circumnavigating the globe in 1579, Drake’s ship, the Golden Hinde, replete with sumptuous treasures raided from forays into Spanish trading routes, found its hull in disrepair, so Drake navigated safely out of the treacherous high seas off the Point Reyes coastline and into calm waters of the curvaceous, protective bay.

He christened it "New Albion", because the alabaster cliffs looming a hundred feet above the shore reminded him of the White Cliffs of Dover. He also proclaimed it English territory.

Doubtful he thought to consult or negotiate with the Miwok about the de facto appropriation, but then again, it’s doubtful the Miwok ever knew about it, and in any event, they would not have understood it since they had no concept of land ownership.

English 1, Miwok 0 (first inning)

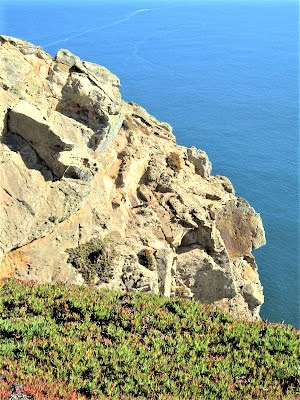

The “white bancks and cliffes” of the sandstone bulwarks noted in the ship’s log are a dramatic and compelling sight, contrasting against the deep blue of the sea, and protecting the bay in a natural amphitheater formation stretching for a few miles in both directions.

Never having laid eyes upon this particular expanse of ocean, where Drake and his crew once encamped for several months, and never having seen the brittle wave-battered cliffs constantly shape-shifting with each new storm or buffeting wind, it feels like I've been transported to another time, another place, heightened by a sense of desolation owing to the absence of other humans.

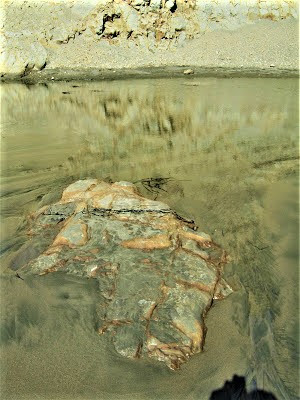

It is all so captivating – the lull of the waves, the refractory play of water on the ocean surface, the glare of the cliffs, the reflections in the shiny mirror of sand, the long-distance views, the animated sights and sounds of avian activity.

Tremendous bird life thrives at Drake's Bay, in and around the estuarial fingerlets, and inland in the fertile and pleasant fields. Swarming on the water, earth and air, flying, lounging, or feeding along the sandy shore digging and pecking for tidbits, uncountable numbers abound.

Gulls, flocks of acrobatic terns, scurrying plovers and sandpipers, troupes of finicky avocets, and squadrons of graceful pelicans comprise a dynamic palette of life, an avian wonderland in a prime feeding ground for a goodly portion of the bird species found at Point Reyes National Seashore.

At last count, 490 different types of birds – 45% of all species found in North America – spend time seasonally or permanently on the peninsula’s 70,000 acres. Such diversity in a relatively confined area is the result of several natural convergences – optimal latitude, variable habitat (coastal, scrub, estuary, grassland, and forest), and prime location along the Pacific migratory flyway.

Quite a few species end up as "stragglers", having been, like wayward ships, blown off course by storms or errant wind patterns, or attracted to the area – sort of like an unplanned detour – by “reports” (instinctual acumen) of easy pickings.

Many seem to like the place, and settle in for a while, such as the Arctic Loon, the Wedge-tailed Shearwater, Palm Warblers and Harlequin Ducks. Every year, Point Reyes hosts a Christmas Bird Count, the 42nd annual one coming up December 18 in which over 200 avid birders will sit motionless for hours attempting to spot new species or increase the number of identified species.

Walking leisurely hand in hand down the infinity of soft squishy sand and surf, the cliffs on one side and the ocean on the other, sandwiched in between two great forces, it is as though the world we are in at this very moment – a world of mechanical non-existence and industrial silence – is pristine, timeless, flawless.

The gentle crashing of waves lapping the shore, the shiny blue water, so perfectly natural and pure, easily lends an impression of a pristine and clean body of water, an Earthly Paradise. Indeed, Point Reyes is reputed to have some of the cleanest beaches anywhere in the world.

And yet, I hate to say it, but it is all an illusion, a sick, sad false reality, because, sadly, no fractal remnant of the ocean is free from contamination; unbearably sad images come to mind – of oil spills and death and devastation; of Texas-sized floating plastic garbage dumps.

All I can see is a struggling bull elephant seal whose neck is sliced deeply by a death noose of fishing line; hapless sea turtles inextricably entangled in gill nets; frantic birds whose bellies are so engorged with plastic detritus they cannot ingest food and die slow, painful deaths of starvation.

Oil and plastic, plastic and oil – yet looking out on the great illusion of oceanic serenity and beauty, you’d never know the repercussions of our addiction. The ostensible perfection of this flawless scene is tragically marred by the grisly reality – out of sight, out of mind to most – of our polluted oceans.

But no sense worrying about things out of my control or spoiling the illusion of a perfectly fine day. We kick back in contemplative relaxation, enjoy a nice lunch, and then resume our meditative beach stroll, until it's time to get back on our bikes and ride up the big hill back to the main road, taking in sweeping views of the bay and the rolling land.

Off in a field I spot an unusual hawk perched on a decrepit wooden fence rail, the likes of which I have not seen before – she’s whitish, with a 51-inch wingspan and a gray-brown head and chestnut breast – an impressive huntress, surely, with her stony, beady eyes capable of seeing up to eight times better than a human, with sharp 2-inch long talons equipped to deftly snatch up snakes or voles on a dive bomb.

Only later was I able to identify her as a Swainson's Hawk – a regal, stoic beautiful bird. I spot a couple more of them, as well as four other distinct raptor species patrolling the near limitless smorgasbord of Rodentia victuals available in the vast acreage of Point Reyes' agricultural and open grazing ranges.

We next head over to amazing South Beach, biking on the road , a stellar experience careening down the polychromatic hill emblazoned with fiery crimson, yellow and orange ice plants contrasting surreally against the deep blue sea and cerulean sky. Normally packed with people, today only a handful of cars are in the oversized parking lot.

We have the entire 19 mile stretch of Point Reyes' shoreline to ourselves, it seems. Where is everybody? (Well, it is a Thursday in October.) The ocean at South Beach is powerful and treacherous, a humble reminder of one's utter insignificance and powerlessness in the face of overwhelming forces.

Only the suicidal would dare to enter the roiling, pounding surf, with its unsuspecting riptides and lethal undercurrents and kiss-your-ass-goodbye sneaker waves. And if one should survive a foolhardy immersion, the 50-degree water will induce hypothermia in a matter of minutes.

Watching a seal frolic and play effortlessly in long tubes of breaking waves with little heads of kelp bobbing up alongside, gives me ample pause to realize how tied to Terra Firma we two-legged creatures are in our naked, natural state, how far we have come from our oceanic origins and lobe-finned lineage.

How evolved is that to become a tetrapod? I wonder. Sometimes I like to think that Cetaceans made conscious choices to not come ashore and evolve as cumbersome gravity-bound land animals.

After staring some more out to sea, lost in thought of this and that nature, I am reminded of the great American naturalist John Burroughs' words on the subject:

“ . . . the creative impulse feeling its way through the mollusk to the fish, and through the fish to the amphibian and the reptile, through the reptile to the mammal, and through the mammal to the anthropoid apes, and through the apes to man, then through the rude and savage races of man . . . to our rude ancestors whom we see dimly at the dawn of history, and thus rapidly upward to the European man of our own era. What a record! What savagery, what thwartings and delays, what carnage and suffering, what an absence of all that we mean by intelligent planning and oversight, of love, of fatherhood!”

Yes, all that!

I spend a good while passing time, thoroughly obsessed in a treasure hunt digging around for pretty quartz and opaline pebbles that litter the beach like discarded gemstones. After a while, I suggest – what the heck, never been there before – that we check out the Lighthouse.

I had been to Chimney Rock before and had parked off the road and bushwhacked down the sand dunes a couple of times to the secluded cove at the base of the Lighthouse cliff, where I once encountered a resting elephant seal who snapped at me because – being dumb and disrespectful – I had gotten too close in order to inspect some scars on his head.

Because it’s the down season, we’re able to drive to the Lighthouse parking lot instead of being shuttled by the Park Service, and here we find the biggest crowds of the day, which are small for Point Reyes standards. The fog we had seen earlier buffeting the headlands like a crown of smoke has dissipated, providing telescoped visibility with clear and open skies for miles in all directions.

We descend the 300 steps to the Lighthouse structure, admiring boulders covered in the strangest furry red lichen, and gaze off to our right and left at dizzying vistas of wide-open ocean, as the cliff faces drop nearly vertically several hundred feet to the rocky shoreline.

Oddly, a buck is spotted grazing in an impossible slope and later is seen making his way up the cliff face more like a mountain goat than a black-tailed deer.

The Lighthouse is a classic structural remnant of a maritime past when many ships foundered offshore and crashed against unseen hazards, colliding with rocks, reefs, and other ships, and often sinking.

The Lighthouse – once manned twenty-four hours a day by four people – and now run by electronic signals – has been a beacon of safety for over one hundred years, offering safe passage to countless ships around the windiest place on the Pacific coast and the second foggiest place in North America. (Winds of 130 MPH were once clocked, and 40 to 50 MPH gusts are common.)

Today, it still functions as an active warning for passing ships, but mainly, it is a museum, preserving a sweet slice of maritime Americana.

From its circular outpost viewing decks, held in check by steel railings, we're able to gaze down to the frothy slate blue water, and that's when someone yells out:

THAR SHE BLOWS!

Well, not that exact expression, but might as well have been. Suddenly, out of nowhere, a gray whale breaches for a second, spyhops momentarily – in which the monstrous head buoys up out of the water and looks around – and then quickly submerges.

I vainly snap a few photographs, but no dice, and give it up for observing the whales through my binoculars, which brings them right into my field of vision as though I'm right there with them. It suddenly dawns on me that this is a first, also – intimate whale watching off the coast of California.

By now, it's getting on 4:30 and the Lighthouse is due to close, and the whale show ends – just as well, since a blustery fog is blowing in out of nowhere with a vengeance.

We walk the quarter mile back to the parking lot enveloped in a chalky veil which shrouds the red lichen rocks and wind-battered cypress trees in an eerie ambience of gloom, so unlike the cheery sunny day we were enjoying just a few moments before.

Occasional breaks give us glimpses of a sun-struck patch of beach way below, a fraction of the ten-mile long straight-edge shoreline visible from these cliffs – an ethereal vision of a wild, untouched littoral world made all the more bizarre by the shrill barking of seals and cacophonous squawking of hundreds of common murres gathered on guano-splattered rocks.

The next day we head inland to the parched Tri-Valley area – a world away from Point Reyes – out near the exurban bedroom communities of Dublin, San Ramon and Pleasanton. Our plan is to check out a slice of Pleasanton Ridge Regional Park which I've been longing to get to know – Sinbad Creek Canyon, tucked down the elusive western slopes of the 1800 feet elevated Island in the Sky.

Getting to Sinbad Creek Canyon from the main staging area off Foothill Boulevard requires a long, tough bike ride or longer, tougher slog of a hike, more than we had in us, so we opted to enter the back way, the relatively easy way – ingress via Kilkare Road out of the town of Sunol. Kilkare Road, while open to the public, is a fiercely guarded private sanctuary / wooded community of homes with many KEEP OUT and NO TRESPASSING signs posted.

.jpg)

At road's end, about fifty feet of private property separates an easement connecting to the East Bay Regional Park District's gate onto the parklands. We take our chances and scoot through, creating no fuss or uproar, and why should it? – we're not harming anyone – and next thing we know, we're in a section of the park I am not familiar with.

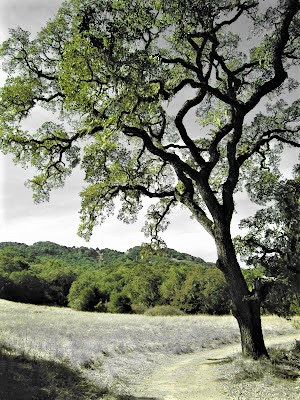

At first glance, it's just a typical dusty, dry as a bone (this time of year) East Bay canyon ecosystem of oak, buckeye, bay, dogwood, maple and sycamore – in short, charming and beautiful, but in a hibernating state waiting for the rains to come and bring it roaring to life!

Sinbad Creek seems like a new and different place, though, because of the sense of isolation and the fact that it’s just far enough out of reach for most hikers and bikers – and 99% of people not in the know will avoid the Kilkare private crossing.

So, you’re left with a sensation of being transported back in time, to when all East Bay nature, indeed most of Central California, looked pretty much like this – only with more oak trees.

Today is a brown, dry, hot day, with the sun bearing down hard. And not a drop of water in Sinbad Creek.

Yet, evidence of big flows during the rainy season will bring me back here to see the creek swollen with powerful run-off from the park's high ridges and steep containment hills – it must be a paradisiacal spot in the vein of Henry Coe State Park during springtime – wildflowers galore, big flows of life-giving magical water, lush grasslands, rolling voluptuous hills, butterflies, dragonflies and birds, puffy clouds, temperate weather.

We bike as far as our hearts care to take us – the rolling trail systems seem endless – explore some legal single-track trails until they start to climb too much, check out a small pond with ducks and ducklings floating about and turkeys strutting their stuff, relax in the grass as lizards pose statuesque on lichen-splotched rocks, and watch juncos and phoebes, nuthatches and chickadees and flycatchers flit about from branch to branch.

According to Thoreau, and I’m in hearty agreement, these winged little delights offer:

“ . . . more inspiring society than statesmen and philosophers.”

Our triumvirate of outings wraps up with a return trip to Marin County – where else when you’ve got a rental and want big nature close by? – where we hike a perennial favorite – Steep Ravine Trail. A thick pea-soup of fog bathes the coastal hills, limiting visibility and making driving conditions treacherous.

By the time we pull-off on Highway 1, just before Stinson Beach, my white knuckles return to their normal color, and the fog lifts and drifts off in wispy tailings, as the day breaks bright, clear and blue – a perfect Indian Summer October day in California.

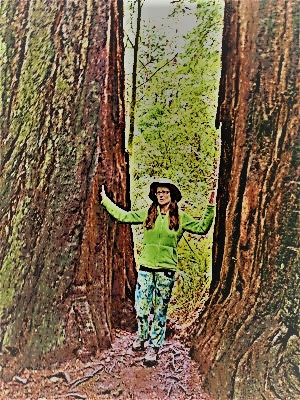

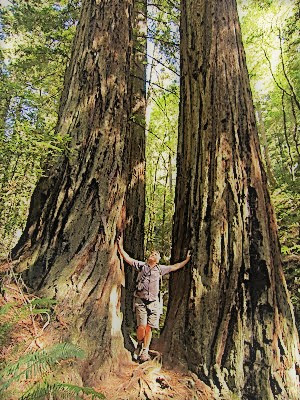

Steep Ravine immediately captivates with its unceasing flow of water – just enough of a lifeblood to enhance the experience of being in the ravine – gurgling and coursing through a boulder-strewn, fern-choked, Redwood-lined creek bed cutting through a rugged slice of Mount Tamalpais' western flanks.

Hints of fall colors and dank aromas of rotting logs and molding humus, enlivened by the pulse of trickling water, lend the day a touch of something special, unnamable, even though Steep Ravine is notable mostly for its big winter and spring run-off which transforms, overwhelms, and inspires the way all big water does.

But even little water is enough to set Gambolin’ Man’s pulse racing and provides pasturage for the imagination of grandiosity and sacred effect ever sought out for simple majesty and beauty of natural expression.

We stop and sit at a favorite spot eating lunch – looking, listening, remaining quiet – next to a normally gushing spot where water has carved channels and chutes, but today gently flows and drops in a subtle rhythm of nature's music, surely nothing to write home about, but deeply touching and spiritual, nonetheless.

We hardly notice the parade of gabbing hikers. A scrub jay lets us have it, wanting some of our crumbs.

The drip drip drip of the little falls is a meditative zen sound that lulls us into a motionless stupor. We finally muster up the energy to continue hiking, as the trail winds higher into the forest, passing ever-larger groves of Giant Redwoods whose stout red furry barked trunks soar to neck-craning heights. Some real beauties grace the banks of Steep Ravine Creek.

On the way back, I reel at the sight of a pool of blood on trail! My first thought is someone really took a nasty spill and busted his head open. Then, off to the side, I see a bloody smear in the grass, and then – the most disgusting sight I've ever encountered on a hike – the discarded entrails of what I assume to be a deer.

But what exactly happened in the short hour we had hiked past this spot? Did a mountain lion or a coyote deposit the grisly stomach and intestines, laying there swarming with flies and steaming on the ground in a stew of blood and feces? It's the only possible explanation.

And what timing, since it would have had to occur during a brief spell when no hikers were passing by – and it was a day of many hikers passing by – so the predator must have dragged the animal down from the higher slopes, onto the trail, disemboweled it purposely or its guts accidentally spewed out, and then tore off up the other side of the ravine with the carcass.

All unseen and unheard!

None of it makes any sense. A knowledgeable friend said a mountain lion would not leave entrails – they go after those first with a relish. Another person said it was a hunter – simply not a possibility given the nature of where we were – Mount Tamalpais State Park in a heavily hiked area.

No doubt, the mysteries of things seen and heard on the trail never end.

The day winds up – or down – by taking a snaking trail from a new Highway 1 pull off to the beach – a gay nude beach, it turns out.

We divert down another path to where some rock climbers are honing their skills on a couple of seemingly unclimbable boulders. We make our way up to the flat top precipice of the biggest rock for sweeping, magnificent views of the ocean, up and down the rocky coast.

Out toward Stinson's scimitar curve of brown sandy beach, past Bolinas Lagoon to the headland point where body-suited surfers – visible through my binoculars like small, bouncing seals – congregate and ride long tubes of crashing breakers.

We sit there for what seems like an eternity, absorbed in a preferred mental pastime – thoughtful nothingness – letting the gentle wind and surging surf overpower our sensibilities, until the elements and the exhaustion of the day takes its toll.

Another day, three days, gone – poof! – in a flurry of time well spent hanging out, hiking, observing natural rhythms, doing not much of anything that anyone would consider exciting or worthy of writing about.

Except, of course, for Gambolin’ Man!

So, it’s time to pack it up, sing a song of praise to the ocean and bid the mountain adieu, and head back home to reflect on all the adventures, each of which would make for a splendid and memorable outing for the ages.

And although we weren’t basking in the glory of Lake Tahoe, or taking in the sublime grandeur of Yosemite, or internalizing the breathtaking vistas of Death Valley or Anza Borrego , or partaking in adventurous outings at any number of bigger, better, more beautiful places – HA!

We have it all right here in the Bay Area! More so, it’s less about where, and more about just being in nature, appreciating it wherever you might find yourself. As the original nature boy himself, Thoreau, expressed it:

“I believe that there is a subtle magnetism in Nature, which, if we unconsciously yield to it, will direct us aright.”

May we forever be directed aright, mates!

Read more Gambolin' Man write-ups about incredible, fabulous, amazing Marin County:

Read more posts from Gambolin' Man on the incomparable and magnificent Point Reyes National Seashore:

Kick back and enjoy 22 videos of various scenes filmed on location at Point Reyes National Seashore:

Take a moment to enjoy some live-action scenes taken in various other stunningly beautiful Marin County locales @

Read more from Gambolin' Man @

.jpg)