ISHI WILDERNESS: Harrowing Descent to Mill Creek Canyon in Yahi Yana Ancestral Territory Worthwhile Despite Travails, Obstacles, a Few Disappointments

.jpg)

I'm high above on a streamside bank, overlooking a sunlit stretch of pooling water, peering through binoculars hoping to spot our furry friend, the river otter. This august morning, silent but for Mill Creek's melodious churning, invites prayer and meditation.

.jpg)

I'm content to stand here, carefree and lighthearted, engaging in what formal spiritual practice I can muster. The mind soon wanders: I imagine a seasonal encampment of the nomadic Yahi Yana, Ishi's people, in this very meadow.

.jpg)

Staring out at fast-flowing Mill Creek, I'm lured into a hypnotic vision: the vibrant spirit and sheer presence of the peaceful hunter-gatherers – the aborigines of what is today called Lassen National Forest in Butte and Tehama counties – pervades my bones.

.JPG)

Themselves respectful visitors to these changing landscapes, the Yahi Yana and related cultural groups came and went, co-existed, migrated seasonally, lived on and off, undisturbed, for 3,000 years, right here.

.jpg)

You could say they knew their way around these parts. Then, by the mid-to-late 1800's, like so many of America's native inhabitants, they were extirpated like vermin by Manifest Destiny-driven European "settlers".

Uh, make that invaders!

.jpg)

.JPG)

One gives the other a quick whack with her thick tapered tail. I'm pleased and amazed at the sighting. Although Lutra canadensis may be cute and cuddly-looking, be forewarned, swimmers, when dipping in otter pools – defensive mothers will bite your ear off if feeling threatened by your invasive presence.

.JPG)

Welcome to the Ishi Wilderness.

It's not for everybody.

One guy hated it so much he packed up and left after a short hike, abandoning plans not so much due to rattlesnakes, ticks, poison oak and heat, but to boredom.

In marked contrast, another chap from Minnesota has been flying to California for a decade to visit the Ishi nearly every year. Take your pick. It probably depends a lot on the time of year.

.jpg)

But if you're anything like Gambolin' Man and love a rich archaeological heritage in a stunning, isolated setting of rugged volcanic formations, soaring red basalt cliffs, and riparian splendor in desert-like conditions, then the Ishi will rock your world.

.jpg)

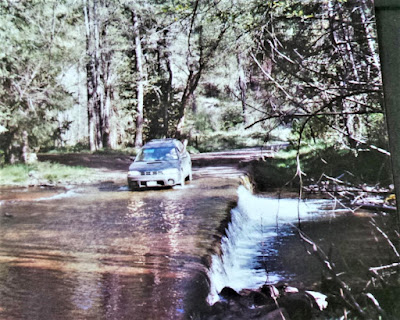

It'll certainly rock your vehicle.

.jpg)

No one said getting to the Ishi Wilderness was a drive in the park. Getting there does indeed require the right vehicle, but even more than that, it demands the right attitude – which will get you there with the wrong vehicle. No one is forcing you to go to the Ishi.

.jpg)

The thing is: you just really gotta wanna go there, see it, feel it, experience it.

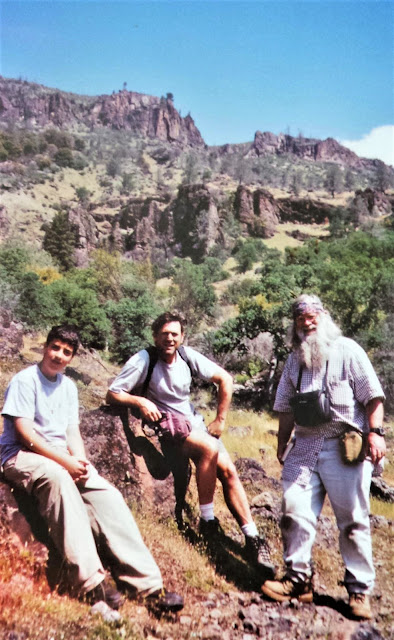

I had to convince Gambolin' Gal, as I did with some friends several years ago when they visited from Wisconsin for a camping trip, that it would be well worth the effort.

Despite travails, obstacles and a few disappointments.

.jpg)

Besides, what's the hurry?

.jpg)

.jpg)

No doubt about it, though – the rigorous drive in requires sharp focus and steady nerves. Even in the right vehicle. Black Rock campground is nearly 30 miles from the nearest main road.

.JPG)

To lighten things up, I joke to Gambolin' Gal, rounding a killer rock-strewn rutted out hairpin of a bend, with a 1000 ft. drop-off to her right:

"Don't you worry, baby! I'll keep 'er on all four wheels!"

.jpg)

Eventually, none worse the wear, we make it safely and soundly. I let out a huge whoop as I shut off the engine in Black Rock's desolate campground situated next to hard-flowing Mill Creek.

.jpg)

YES! All to ourselves!

.jpg)

Which is to be expected, after all, given the amount of time and effort required to get here.

.jpg)

So far as Gambolin' Man's concerned, this Mill Creek is the king of California's 100 Mill Creeks. It is one of the Sierra Nevada – Shasta Cascade's last free flowing foothill streams, and 32 miles are under consideration for National Wild and Scenic River System status.

.JPG)

It lays claim to having the best aquatic habitat in the mountain range's 100 major watersheds. That's saying something!

.jpg)

It begins a meandering 49-mile journey in higher-up Lassen country and flows unimpeded to join with the Sacramento River in California's great central valley.

High above loom volcanic cliffs, springs, oases of green difficult to find, and famous "pineries" – dense stands of Ponderosa pines growing on high ledges left untouched during Mill Creek's carving of the canyon.

.jpg)

Its boulder-and-log strewn waters harbor significant runs of winter steelhead trout and spring Chinook salmon, who swim up to 6,000 ft. to spawn.

.jpg)

And no small wonder that river otters also call the chill waters home, and with 150,000 hairs per square inch, their fur coats allow the aquatic weasels to roam freely up and down Mill Creek in blithe search of fishy gourmand delights and other critter canapés – crayfish, frogs, snakes.

.jpg)

The canyon extends through the heart of the blazing hot badlands, whose 41,000+ acres abut range and ranch lands and encompass a State Game Refuge, protective of California's largest migratory Tehama deer herd, black bear, wild hog, mountain lions, coyotes, bobcats and rabbits, not one of which we encounter.

.jpg)

With the exception of a month or two in spring and fall (when temperatures are moderate and ticks, rattlesnakes and poison oak are less abundant and threatening), the Ishi Wilderness remains a mostly inhospitable place.

.jpg)

If you'll believe all the web sites. Nearly every posting describes it as a land:

" . . . incised by wind and water, dotted with basaltic outcroppings, caves, and bizarre pillar lava formations."

.jpg)

All warn of temperatures in the shade surpassing 100 degrees, and of disease-carrying bloodsuckers (ticks and mosquitoes), lethal venom injectors (rattlesnakes and scorpions), and miserable rash inducers (poison oak, stinging nettle). Not to mention bothersome fox tails and velcro-like burrs.

.jpg)

Oh, such constant worries! Plus, it's tinderbox dry and hot as Hades! For chrissakes! – what are we doing here? We're told, of course, NOT to take our passenger car down there, an act of pure tomfoolery, and certainly we're exhorted NOT to go there at this time of year – in the dead of August – for fear of succumbing to heat stroke or dehydration.

.jpg)

Or getting bitten by a rattlesnake. Or worse. Well, fact is, summers are downright deadly in the Ishi Wilderness. Minus the cacti, it might as well call itself a desert, for it is an unforgiving, harsh, exposed landscape where you don't want to screw up or find yourself unprepared, no matter the time of year.

.jpg)

Do not take the Ishi Wilderness lightly. Enter with respect (and caution!), and the land will welcome and sustain, for there is water out here! Without these spring and snowmelt fed creeks, this place would indeed be a forbidden anti-paradise.

Water makes all the difference in the world . . . the life-sustaining force that brought Ishi and his people to this area for seasonal migrations to gather acorns, hunt deer, rabbit, wildcat, fish, to live peacefully off the fat of the land for millennia.

.jpg)

Until August 29, 1911, when a dazed, starved Ishi – the last existing Yahi Yana individual – was captured in a slaughterhouse corral outside Oroville, California (a locale dripping with irony), bereft of his senses, his strength, his entire past and place in the universe.

Today, an oak tree stands where Ishi was spotted.

.jpg)

On arrival in Black Rock campground, relieved, we let our nerves settle a bit, savoring the baking smells of brush and trees, and soaking in the silent grandeur of the moment. I pop open an ice cold one.

.jpg)

We then pack a lunch and prepare to head out for a hike, even though it's the hottest part of the day. No worries, we're carrying plenty of water, and Mill Creek's refreshing, shady pools, not more than a couple of miles away, await us.

.jpg)

The first part of the hike takes us along a dusty road and through a private ranch – a cattle grazing operation, how yucky – the last thing you'd expect to see out here. But cattle grazing operations are common in our natural resource treasure areas, unfortunately.

.jpg)

Most of the cows are long gone, having been fattened up and shipped off to slaughterhouses, but their dried-up paddies are everywhere along a stretch leading to the lower Ishi meadows. At least it's better than the first time here in late Spring with my Wisconsin friends, when we trudged through wet cow poop mushy terrain – just appalling.

.jpg)

Gambolin' Gal is outright disgusted, wanting to know if I knew beforehand there were cows. I fudge. She barely deigns to swim on this hot day, pointing out that all the polluting waste no doubts seeps into the ground and drains into the creek.

In beauty and cow shit we walk.

.jpg)

We nonetheless spend several hours luxuriating in a quiet pool, exploring leisurely, hanging out on a rocky beach head. Doing what we do best under these circumstances – nothing. During a lull, I hear music and voices, but it's only the river singing, the breeze providing harmony.

.jpg)

The at-once peaceful and unnerving sense of being all alone out here nags constantly at my soulstrings. On the hike back, the sensation becomes a premonition of unwanted reality as we crest a final hill and hear the background boom boom boom – not of the forest grouse – but of some idiot's loud bass technopop reverberating from one of the camping sites 500 ft. from ours.

.jpg)

Crestfallen, as you can imagine, we do our best to ignore this profound and dreaded intrusion, sitting by the river to let that help drown out the awful, alien noise. What's with people? I do my best to not get all righteous and inflamed and go running over to confront the dudes.

.jpg)

Calm down, now, Gambolin' Man, calm down! Drink another ice cold one.

.jpg)

Shortly, two college-age guys approach us; again, I put on my best face of civility. They're actually nice, polite young fellers, and I give them credit for their communication skills, it's just that their idea and our idea of a "good time" is about as antithetical as you can get.

.jpg)

Turns out, he tells us, once a year – and this just happens to be the chosen weekend – he and all his college buddies gather to party down in the sticks, it's like a tradition, you know.

.jpg)

He informs us that about 15 or 20 more revelers are due to arrive later in the evening. Oh, great, I say, so there's going to be a party, loud music? Yeah, he nods, telling us he'd do his best to keep things down and keep everyone grouped in the adjacent camp sites. Wonderful, I tell him – we've driven 20 hard-ass miles to come here for a wilderness experience, and this is our reward?

.jpg)

We thank them anyway and just have to suck it up. In days past, for most of the twentieth century, the Ishi Wilderness remained unvisited, unknown, accessible and interesting enough only to those with a will and a way. But today's SUV / off-road culture makes the going easy, and now anyone with a 4-WD or high clearance vehicle can easily make the trip:

. . . from Yahi to Yahoo . . .

.jpg)

.jpg)

Hopefully, everyone who does visit the Ishi Wilderness today, does so with respect (and caution!). But clearly, not all are in search of peace and quiet, spiritual communion and remote solitude.

.jpg)

Some people are rude and stupid and completely unskilled in the ways of being in nature. May they incur the wrath of Ishi, if such a thing is possible; or shall they be forgiven for their unforgiving ignorance?

.jpg)

For them, nature is just a backdrop in which to get drunk and party down. Which is what they do all night long. Hey, I'm no curmudgeon, no ageist, but this is ridiculous!

.jpg)

Most of the night, there's incessant whooping and hollering, loud and louder music, then it shuts off for a while, then resumes, but in a lower pitch, like they're really concerned and trying to be "good neighbors."

.jpg)

Now, someone has inanely hung a lantern nearby – one of those monster spotlights Gambolin' Man so reviles – so that they can "see" – what? – when they have to pee?

.jpg)

I'd have shot the lights out of it if only I had my .22 handy!

.jpg)

.jpg)

Finally, eventually, deep in a painful fog, the noise ends, the party hardy dudes are down for the count, and all is silent night, but for the cacophonous chirping of a million crickets, the wind caressing the trees and the river gurgling its magical song.

Aaaah, truly soul-soothing sounds of music to lure us to sleep.

.jpg)

FINALLY!

.jpg)

We rise at dawn and decide to depart a day early, no surprise. We spend all morning hiking Mill Creek Trail in the opposite direction, east toward the higher Lassen country. The morning is hot, beautiful, perfect – who says you can't enjoy the Ishi in summertime?

.jpg)

Mill Creek Trail passes through wide open meadows rife with blackberry brambles and oak woodlands hosting wild turkeys, quails, mourning doves, and many songbirds. Little drainages still release jet streams of water down gullies. Big views prevail of the high, basalt cliffs.

.jpg)

Eventually, evidence of little use, the trails peters out into thickets and brush, and we turn around toward the vision, again, of ever-intriguing, impressive, massive Black Rock – also pink, salmon, red and lavender colored – a gigantic plug dome dominating the surroundings with the intimidating presence of a super-powerful Earth force rendering all else tiny and insignificant.

.jpg)

Black Rock, a 250 ft. tall remnant of an ancient volcano whose impenetrable bulk forces the high-volume creek to cut a course around its rock-solid contours, a truly splendiferous thing to behold.

Standing in awe, feeling the spirit of place, the power and energy of it all, watching rugged Mill Creek steamroll around the blackened rock's anchoring bulwarks and plunging headlong through a series of chutes and cascades into a gorgeous pool.

.jpg)

Black Rock surely awes and inspires – and alone warrants the trip in, to stand at this sacred altar of worship for the Yahi Yana, and for those of us who (respectfully) follow in their footsteps.

.jpg)

Seeking to know, find and rediscover our place in the universe.