PINNACLES NATIONAL PARK: Endless Hiking Among Otherworldly Rock Formations of an Ancient Volcano in Central California’s Gabilan Range

.jpg)

One splendid October morning, hiking a deserty landscape with stellar views in all directions, we’re hoping to catch a glimpse of Hoi, or one of his juvenile minions, high on Condor Gulch Trail. At the crest of High Peaks Trail, still no sightings.

.jpg)

Then, scrounging around in my pack for a banana, Mary points up, exclaiming, “There’s one! Quick, look!” I fumble about and manage to look up into the cerulean void barely in time to spot a big, ugly turkey vulture circling overhead.

.jpg)

I quickly affix binoculars to eyes for a better look – I don't see an ID tag, but there’s no mistaking the tell-tale triangular white underpatch I see for a nanosecond on one wing.

.jpg)

This is the wondrous, near-extinct California Condor! In moments, this bad boy’s gone, soaring out of sight behind towering red ramparts, not to be seen again during two days of spectacular hiking and exploring in beautiful Pinnacles National Park.

It was / is a noble effort by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, in cooperation with the Ventana Wilderness Society, to bring the largest flying bird in North America back to its traditional craggy nesting grounds.

.jpg)

Three years later, according to Ranger Mike Rupp, whom we met and spoke to at length in a high pinnacle rock garden, only thirteen of the high-flying, long-winged, delicate (as in bio-ecologically fragile) birds roam the airways above Pinnacles National Park today. (The lot of them being juveniles, breeding among them is years away . . .)

Will these magnificent birds be able to survive in their reintroduced habitat for another several years until they reach breeding age to successfully propagate and bolster their diminishing numbers? Not without help and public education. Natural hazards do exist, but, according to a National Park Service press release in 2003:

.jpg)

“Much greater is the danger posed by humans. The preeminent threat to condors is lead poisoning, caused by consumption of lead-contaminated carcasses or gut piles left behind by hunters. Few people are aware of the danger lead poses to condors . . . These threats can be mitigated through the use of lead-free ammunition or burying animal remains.”

.jpg)

Ranger Rupp informs us that one ailing condor was recently captured to undergo chelation therapy; since 1997, five have died and twenty-six more have undergone emergency treatment. (Condors are about ten times more sensitive to lead poisoning than their cousin, the common vulture.)

.jpg)

Pinnacles National Park is one of those “special, cherished” places I’ve always meant to check out . . . but never have until October 2006! (Surely, I’m alone in this department!) What have I been missing these many years of seeking out new places, discovering the exotic in the local, the universal and wondrous in the commonplace?

After all, not just any old park has National Park status bestowed on it. Here is an uncommonly intriguing natural area as close or closer than Point Reyes National Seashore, Henry Coe wild lands, Marin / Sonoma / Napa / Yolo counties, the Santa Cruz Mountains, all places I regularly pay homage to.

.jpg)

Pinnacles National Park is as close or closer than beloved destinations to Sierra Nevada foothill canyon / river country.

On more than one occasion, it’s taken me nearly as long to get to the back side of our local Mount Diablo State Park! So what gives with NEVER having EVER visited fantastical Pinnacles National Park until now?

(Although not at a loss for words, Gambolin’ Man cannot explain it.)

.jpg)

Our initial impression is of a remarkable, out-of-place landscape more akin to the desert Southwest than to the otherwise unheralded Gabilan Range in the otherwise un-touristy, highly agricultural San Benito County.

.jpg)

[From Wikipedia: “ . . . home to benitoite, the official gem of the State of California and of E Clampus Vitus, to the San Benito evening primrose (Camissonia benitensis), a flower believed to exist only within the county, and to Illacme plenipes, a millipede discovered in the county in 1926 (and unseen again until 2005) and having more legs than any other millipede species.”]

.jpg)

Approaching from the funky town of Soledad, the long and winding road rolls through chaparral hill country, beautiful and remote-feeling to be sure, but just that – a feeling. We’re surrounded by private, fenced-off ranch lands with NO PARKING NO STOPPING NO CAMPING signs conspicuously posted along the way.

In other words: KEEP THE HELL OUT!

.jpg)

.jpg)

We’d been driving all day, up from wine country in Paso Robles, so by now, it’s getting on; we’ve got about two hours to get out and see what we can see. It’s amazingly warm, as dusky light softens the edges of rugged, dark purple hills.

.jpg)

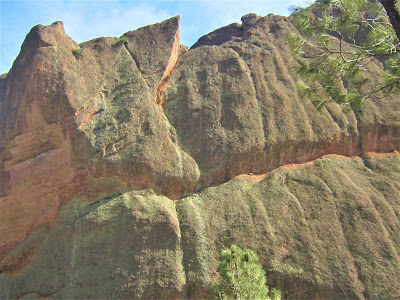

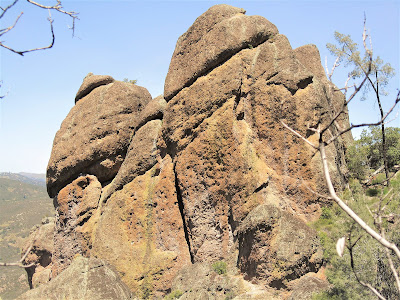

We round a bend in the road, in this otherwise unspectacular place, and suddenly they appear on the elevated horizon – a panorama of surreal red rock spires, imposing monoliths, and Arches National Park-like pinnacles rising anomalously out of rolling hills.

I am flummoxed, nearly speechless, to behold such a magnificent heretofore unseen sight, close to home or not.

.jpg)

We self-pay at the unstaffed West Entrance Chaparral Ranger Station, and set off on Juniper Canyon Trail, a winding, steep and narrow trail that gains over 1200 feet in elevation in under two miles.

We decide to take it easy, venturing just far and high enough to kick back and take in a mind-boggling view of gigantic penis rocks, gargantuan rabbit figures, mushroom mosques, and other fabulous rock formations towering above and around us.

.jpg)

Evening autumnal sunlight diffuses the scene, creating a soft, pastel dream world. In celebration of our eleventh (or 21st) anniversary, we hoist a toast to our eternal love, with ice-cold champagne, right there. Despite ten cars and a group of “moonhikers” in the parking lot, we don’t see or hear a soul and have the place all to ourselves.

.jpg)

It is sweet, serene, surreal and pristine. The all-pervading peacefulness and silence amid such stunning natural beauty recalls Death Valley or somewhere much farther away than an hour or so from San Jose!

.jpg)

In a few minutes, I feel light-headed, ethereal, awestruck – make that numbstruck – by the unfolding display of nature’s impressionistic light show, created by a phantasmagoric sunset, against a canvass of raw, naked rock, at the magical crepuscular hour, when the "crack between two worlds" opens up.

.jpg)

The next morning finds us at the East Entrance, the primary portal to Pinnacles National Park, with a Visitor’s Center and a campground (outside of the park). Driving slowly in, we spot numerous deer foraging off the roadside.

Only a couple other cars are parked on this perfect, bright, lovely morning . . . When suddenly, a park maintenance guy cranks up – you guessed it! – a noisy, obnoxious gas-powered leaf blower!

.jpg)

In this remote place of splendid isolation and quietude, with nothing on the ground to even blow away, for crying out loud (except toxic molds and asthma-inducing dust), I’m being driven to despair and psychological torture by an NPS employee “cleaning up” with an ear-piercing, brain-rattling, bone-jarring, cell-shattering leaf blower!

I am outraged and appalled, disheartened by the irony that Pinnacles National Park, priding itself on Class I Air Quality, and purity of wilderness, allows the stupid polluting contraption to be used.

It’s a bit like vacuuming the pews during mass with a Dirt Devil.

.jpg)

Hike / loop options are diverse. Trails that lead to back wilderness areas of the canyon system of Chalone Creek watershed must be absolutely splendid and magical places to be during wildflower season, and when the water is flowing merrily along, and the birds are singing melodiously, and the butterflies are merrily fluttering along.

.jpg)

I know this feeling well, so aptly embodied by Rabindranath Tagore:

"The same stream of life that runs through the world runs through my veins night and day in rhythmic measure. It is the same life that shoots in joy through the dust of the earth into numberless waves of flowers."

We opt to hike up Condor Gulch Trail to High Peaks Trail, then reverse loop it back down High Peaks to Chalone Creek and eventually Bear Gulch Trail back to the Visitor's Center – all this, about seven grueling miles.

.jpg)

After a two-mile side-detour, of course, to check out the “steep and narrow” section of High Peaks. In the distance, due south, are the twin Chalone Peaks, North topping out at 3304 ft., South dominating at 3269 ft., very alluring destinations, indeed, but for another time.

.jpg)

Today’s loop, though strenuous and punishing – but well deserved – provides us with unparalleled variation – changing scenery, surprising topography, unexpected microclimates, diverse vegetation, and intergraded ecosystems of woodland, riparian, chaparral, grassland.

.jpg)

The entire hike I’m craning my neck looking for condors, or stooped over inspecting a particularly intriguing pyroclastic conundrum, or stopped dead in my tracks admiring one superb vista after another.

The entire hike simply challenges my conceptions of what to expect in the central coast ranges of California – certainly not a veritable desert Southwest sort of ecosystem, a place where north meets south, west meets east, where floral and faunal communities from each zone intermingle and survive endemically.

.jpg)

The entire hike simply defies my imagination, baffles my understanding, in a genuine effort to get my head around the VERY BIG IDEA of a migrating volcano – moving at 2 to 3 centimeters per year – displaced by unimaginably titanic earth forces, inching its way northwestward over eons.

.jpg)

It's a very difficult concept to grok – how faulting, shifting plate tectonics, and erosion have worked, over the course of 23 million years, to carry and shape the better half of a volcano (the Neenach, originally the size of Mount Saint Helens) from southern California’s high desert area to its current residing place.

.jpg)

To envision this trans-human process unfolding as a literal act of geologic reality is near-impossible. And yet it happened – a cataclysmic explosion, a long day’s journey into eternity, the Southwest transmigrated, thrust ever-so-slowly northwestward to 195 miles away in the Gabilan Range!

This process is still happening: Pinnacles National Park continues to suffer entropic long-term effects of erosion and shifting plates resurfacing the land – the monument will “soon” be somewhere up in Washington state, and eventually, in maybe 75 million years, it will cease to exist. Better enjoy it while we can!

Pinnacles National Park is a mere two and a half hours away (if you’re lucky enough to live in the San Francisco Bay Area). A lifetime can be spent returning there time and again – we’re excited to next return on a lovely full moon to night hike the talus passages and high winding trails in Albion glow.

(Ranger Rupp informs us that the East Entrance remains open past posted closing hours for adventurous and exotic night hiking during temperate full moons.)

Or maybe we’ll just pop down on some blisteringly beautiful March day, when the resurgent new season is upon us – when bone-dry gullies and water courses come roaring to life with run-off; when vast swatches of wildflowers color the hillsides; when you’ve got the paradise to yourself.

.jpg)

Situated just east of the famous Salinas Valley, Pinnacles National Park exists as an island in time and space. It exists as a soul-soothing retreat, oh-so-close yet so-so far from the madding crowd (despite the excessive numbers that visit yearly).

By dint of geologic anomaly, it exists here in our very midst, 26,000 acres of protected territory, increasingly threatened by cancerous urban encroachment and deleterious human activity.

Pinnacles National Park exists as a place to supremely commune with Mother Nature – according to the National Park Service, you are apt to spot anywhere from:

.jpg)

“ . . . 149 species of birds, 49 mammals, 23 reptiles, 6 amphibians, 68 butterflies, 40 dragonflies and damselflies, nearly 400 bees, and many thousands of other invertebrates.”

Yes, Pinnacles National Park exists as a unique place to learn about cultural history – Costanoan Chalone and Mutsun peoples habituated the area for thousands of years in search of the Santa Barbara sedge for weaving, acorns, plants and animals for sustenance – to learn about geology, and the fascinating natural world of diverse ecosystems and natural features.

.jpg)

Indeed, and ultimately, Pinnacles National Park abides by its own natural rhythms and cycles, existing independent of and beyond the purviews of the tiny human perspective.

.jpg)

So we go there to ponder, reflect, admire, and soothe our soul.

Read Gambolin' Man's other post extolling the marvels and wonders of Pinnacles National Park: