NEW MEXICO: A Sojourn Across the Great Divide of Time, Digging Through Strata of Culture & History, Uncovering Layers of Consciousness & Mystery

"This land, the plants, the hills and mountains mean a lot to us. It is home – full of peace and harmony. At times it is dry, other times there is rain and snow. I belong to this place."

- Donald Suina, Pueblo de Cochiti

Phanerozoic Time

Paleozoic Era:

500 million to 250 million years ago

A vast shallow ocean swallows up the present territory. Sedimentary deposits accumulate, perfect fossil tombs for New Mexico's first residents – thriving marine invertebrates such as brachiopods, nautiloids, coral, crinoids and trilobites.

Primitive trees take root, ancestral ferns and giant horsetail grow profusely along shorelines, amphibians and winged insects spontaneously proliferate. Toward the end of the era, an unforeseen extinction event occurs, wiping out 95% of all life.

Earth convulses, upheaving two billion year old Precambrian rock, and the ancestral Rockies in the central and northern part of the state take shape. A great barrier reef forms in the south, eventually left high and dry when the primordial sea dries up, evaporates and deposits a triumvirate of minerals – salt, potash and gypsum.

The latter will erode from alabaster mountains, wash down to the basin, and be swept up in great gusts of wind to form present day's White Sands National Monument near Las Cruces.

Mesozoic Era:

250 million to 65 million years ago

Atmospheric CO2 levels are four to five times what they are today. Then, without warning, in an instant it is all gone – a gargantuan asteroid crashes off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, obliterating the dinosaurs and most all of life in a catastrophic impact event.

Cenozoic Era:

65 million to 3 million years ago

More tremendous volcanic eruptions follow, forming the Jemez Mountains, Capullin Peak and Mount Taylor, explosions that spew forth from the molten bowels of the planet pyroclastic flows that contribute to the state's complex geology of red, pink, orange, and salmon depositions eroding over millions of years to form today's rugged mesas, badlands and iconic desert beauty.

Pleistocene and Holocene Epochs:

2 million to 10,000 years ago

Vast herds of animals roam fertile plains, anatomically modern humans arrive on the scene, and a period of interglacial conditions allow a flourishing of cultural beginnings, engendering a different kind of explosion never before witnessed on the planet – an explosion of human activity and dominion over earth and its creatures.

Archaic Period hunters and gatherers – so-called "Clovis" people – announce their presence about 11,000 years ago with distinctive prototypical flaked projectile points found at Clovis, New Mexico; they fasten them onto spears to hunt and kill mastodons, mammoths, camels, horses, and to defend against other predatory animals, notably the saber-toothed tiger.

These resourceful Paleo-people, the most famous and well-known of Pre-Columbian Amerindians, were long considered to be the primogenitor human inhabitants of the New World, the ancestral population of all indigenous cultures in the Americas.

Not so fast.

And so, despite official dogma in archaeological textbooks, the mystery remains . . . as do so many mysteries which remain, surrounding New Mexico’s prehistory.

Archaic Period:

5,000 years to 600 years ago

Descendants of the Paleo-Indian hunter-gatherers and Basket Weaver traditions learn that a tiny seed from Mexico, if planted in the right soil conditions, and nurtured properly, and propitiated fervently to, can produce an abundant and unlimited, versatile supply of food.

Enter the all-mighty grass known as maize. Rounding out the nutritional trinity with beans and squash, the foundation is laid for a corn-based agricultural way of life that enables bands of disparate peoples to come together in settlements, in organized, stratified, and hierarchical societies.

The Ancestral Puebloans seek out propitious sites with water sources and abundant game for building their villages, dwellings and ceremonial centers; they gravitate to remote (only from our point of view) canyons where they build multi-storied cliff dwellings high in secluded alcoves.

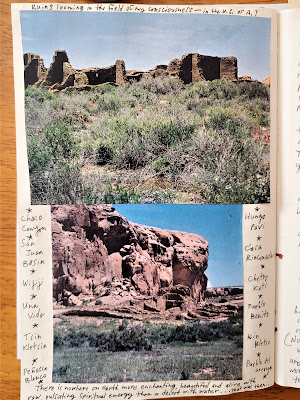

They begin engaging in communal living, dwelling in long houses tucked up against the sheltering bulwarks of soaring canyon walls. They construct sophisticated apartment complexes – complex apartments – in unlikely places such as Gila, Bandolier and Chaco Canyon, where the ceremonial centers of Chetro Ketl and Pueblo Bonito served as cynosures of culture, long-distance trade and commerce, art, spirituality, and community building.

Historical and Present Time:

600 years ago to present time

It is the period of the Spanish Inquisition in New Mexico (1626), the rooting out of pagan cultures, full-scale oppression and subjugation and conquering of once proud and free peoples.

New Mexico is ruled by the Spanish, the Mexicans, the French, the Texans. Apache and Comanche raid Hispanic settlers, are pegged as terrorists by U.S. Army occupiers, yet remain wild and free outliers / outlaws until the bitter end of their resistance.

In 1912, New Mexico becomes the 47th state in the union, a “wasteland” state where atomic bombs would shortly be built and tested.

March 2010:

New Mexico, U.S.A.

Places of magic and mystery, charm and history: Chaco Culture National Historic Park, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, White Sands National Monument, Three Rivers Petroglyph Site, Petroglyph National Monument, Bandolier National Monument.

Places in the desert Southwest that remain alive and vibrant with spiritual energy for the present-day Pueblo Peoples who have carried on age-old cultural traditions in and around these marquee sites of human prehistory and geological natural wonders.

We are on a whirlwind Möbius strip loop through New Mexico's desert / mountain landscape, burrowing through immense layers of geologic time, sifting through the strata of cultural chronologies. We are beholden to the rich legacy of the human drama that has unfolded for tens of thousands of years.

We are, every which way, every day, in constant awe of New Mexico's geologic rainbow of topographical features, revered as sacred places since time immemorial – eerily lonesome desert plains and lushly forested plateaus, dozens of heaven-scraping mountain ranges, free-flowing rivers and alpine extremes, volcanic badlands created from the detritus of ancient volcanic explosions and caldera implosions, stark ridges, colorful mesas and buttes.

Transcending all barriers of time in this land of eternal quietude and tranquility, we are, though, only getting a teasing glimpse of the past and present, a peek into the full spectrum of each place’s local color and lore.

New Mexico’s moniker – "The Land of Enchantment" – is well deserved, for not many places rival the state for sheer, well, enchantment – that quality which casts a spell on you or transfixes your imagination with awe and wonder, such as this land of diverse geology, variable climate, ecological differentiation, and storied cultural pageantry and historical events is capable of doing.

An unprecedented changing landscape has resulted in an ever-shifting ecotone – and consequently, a rich and varied natural world comprising six of the seven life zones identified on Earth. Such a rich biota has enabled an incredible number of animal and plant species to thrive in the transition zones from 3000 ft. elevation to 8500 ft. and higher.

Albuquerque and Tijeras Time:

Visiting Amigos

She would then be heading on to Moab to run the Spring marathon, like she has the past several years. But about a week before our scheduled meet-up, she calls and says in a crackling voice that she won't be coming. Her Greek God boyfriend, Yiannis, broke his pelvis, and evidently, being in a depressed state of mind and hapless physical condition, requires her tender ministrations back on the island of Salamina where they live.

But we’re still on to spend time with Pia, and so for the next few days, we are her, and her children’s, guests in their lovely, sprawling adobe-style home. Two of the kids, Alma and Che, are out of school, while the oldest daughter, Luna, is attending a language academy in Guadalajara. The last time we saw Pia, Luna was about two, and Pia was pregnant with Alma. Che wasn’t even a gleam in Pia’s eyes yet.

One evening we check out some musical acts at the historic El Rey Theatre in downtown, regaled by native New Mexico bluesman Stan Hirsch – he’s real good - and quirky singer / story-teller Steve Poltz. The El Rey is a funky old-school ballroom style place and only about thirty people have paid to watch these two relative nobodies. The baroque décor, sparseness of the rather unenthusiastic crowd, and the echoing emptiness leave us feeling like we’re in a David Lynch flick.

Another day we drive up to Jemez mountain territory, about an hour away, and hike on a snow-covered jeep road, and then return to fiddle around in the stunning Rio Guadalupe gorge. A tumbling stream crashes down through a narrow slot corridor, where we play and sit by the running water, absorbed by the beauty all around.

Pia, Che and Alma are in adventurous mode, and crisscross on slick rocks making their way downstream along cascades and pools. It's our first breath of nature in New Mexico, and we relish it.

We then head over to the Bodhi Manda Zen Center, in Jemez Springs, where Pia had been a few years ago, for a delicious, relaxing soak in some of the nicest natural mineral hot springs I’ve ever had the privilege to dunk my aching body in.

Amazingly, we have the place all to ourselves, which is unheard of, in California, that is, but I guess most people opt for the public bath house or the other nice spa resort, Giggling Hot Springs. (We are, but don’t yet know it, destined to return here a few days later.)

The tranquility and beauty is arresting – steaming travertine pools reflecting Buddha statues, old wooden fence, white tipped water birch trees and snow-sprinkled red mesas, with a pretty stream, the Jemez River, flowing along the back of the property.

Another day, Pia, Alma, her cousin, Marina, Pia’s friend, Joe, and us pile in her beat up old van for a visit to the Sky Pueblo of Acoma, about an hour west. So here we are, coming down from a curvy crest to the valley floor, when – THUMP! – the rear tire blows. We’re about ten minutes from the Visitor Center, and the last tour to the Pueblo is at 3 pm.

Can we make it? Well, wouldn’t you know it – the tire iron is nowhere to be found! Pia blames her ex, Victor, for taking it out. Whatever. There is some tire fill goop under the seat that Alma triumphantly holds up, but the connector straw is missing, so it's useless. And, there's no cell phone reception.

Great. Pretty soon, a group of Harley riders come by and Pia flags them down to take her to the Visitor Center, where she's able to call Triple A. Meanwhile, an Acoma security guard stops and nails me for taking a picture of Alma and Marina posing on a rock. We’re on tribal reservation land and no photographs are allowed without a permit.

.jpg)

Still stuck, Pia decides to hitch a ride back to the center. We’re in luck – an Acoma family picks her up and turns back around to help us. They have a jack and soon the under-sized spare is bolted on, but, alas, it's too late to visit the Sky Pueblo. I can see it up on the mesa top through my binoculars, looking indeed like a pueblo in the sky. Quite charming, not something you see in the states every day.

The Acoma family, though, is the next best thing to visiting the pueblo – maybe even a more authentic experience, for we’re able to speak with them and learn a bit about them. For instance, they were on their way to a secret well to gather water. They had just chopped wood. They live as their ancestors have lived for thousands of years – without electricity or running water.

And they strike me as some of the happiest people I have ever met.

We squeeze in a visit to Petroglyph National Monument, an easy-to-underappreciate (at first glance) site situated on the undeveloped outskirts of west Albuquerque. The preserve is the site of a volcanic basalt escarpment, with much rock and boulder rubble falling down high hillsides, which ancient passers-by, including more modern Spanish interlopers, used to inscribe multiple thousands of rock symbols marking their territory.

It begins to snow flurry during our short hike. We brave the elements, trudging up along a sandy path winding through eroded volcanic hills. Soon it becomes apparent how extensive and interesting a place PNM is – stretching as it does for 17 miles along Albuquerque's West Mesa and featuring five volcanic cones, over 20,000 petroglyphs, and hundreds of (mostly unnoticed) archaeological sites.

Unfortunately, we’re short on time, unprepared, and the weather’s turning nasty, and so we turn back having seen only a fraction of the images.

We take a wonderful little walk in the Rio Grande Nature Center, right near Pia's home, a 166-acre preserve sheltering the world's largest stand of Rio Grande Cottonwood trees, which form the bosque, or woodland arboreal oasis.

In one 75 ft. tall tree, I hear the screeching sounds of a skirmish going on between two ravens and – glancing up – I'm amazed to behold a nonplussed Golden Eagle, a regal creature holding court high above, clinging to a snag with sharp yellow talons that could disembowel a human, looking down into the brush piles for a tasty snack to emerge from a hidden den, not a feather ruffled from the ravens' constant harassment.

(I understand that they eat the ravens' eggs, so who can blame the feisty birds for bugging the eagle.)

After heartfelt goodbyes with Pia and her family, we next spend a night with long time amiga, Cindi, who’s lived in Tijeras, in the Cibola National Forest, in a beautiful hand-constructed adobe home at nearly 8,000 ft. above sea level, for – what? – 20 years now.

We meet in town at a cafe near the university, where she's with her now twenty-year-old daughter, Lexi, who was just twelve when we last saw her. All grown up now, she wants to be a fashion photographer, but first, time out for the pre-college ritual of tramping around Europe for a few months. Cindi sighs (as if you didn't do plenty of trampin' around, girl, in your day!).

We follow her the back way to Tijeras, and pulling into her place of rustication, her two dogs, Toby and Chula, greet us effusively. Chula is sixteen and we remember her – she us? – from our previous visit in '98. Cindi's boyfriend, Brian, is there, too – a fine fella perfectly suited to Cindi's fun-loving temperament – and we all sit around a cozy fire drinking wine, talking, laughing, and reminiscing, as a big snow storm dumps three feet by the next morning.

Three Rivers Petroglyph Site:

Outdoor Art Gallery Challenges Conventional Beliefs, Defies Traditional Interpretations

Maybe so, if you're not into rock art mysteries. The basin is bordered on the east by the Sierra Blanca Range in the Sacramento Mountains, and the west by the unbroken chain of Franklin, Organ, San Andres, and Oscura ranges. Thirty miles to the southwest lies a glinting patch of Earth – White Sands National Monument.

The Tularosa Basin Conference of 2009, convened to bring attention to what its organizers call the true Land of Enchantment, hails the 6500 square mile basin as possessing:

" . . . a deeply rich culture history that extends from the early Paleoindian period, nearly 12,000 years ago . . . through the historic period often represented by colorful, yet tragic events, including settlement of the basin, founding of villages and towns, conflict of ethnic groups, dispute resolution (old-West style), development and resource exploitation, and military impacts and expansion."

Looking west, it is a gentler, brighter day, with puffy cumulus clouds smattered above the horizon of the San Andres range. Here at the northern terminus of the Chihuahuan Desert, life exudes harshness and inhospitability, and yet, because of the basin's only perennially flowing stream, people have been able to carve out a living here, and many plant and animals have adapted and manage to flourish.

We're greeted at the entrance by an old fart volunteer who, bored by lack of visitors to his remote kingdom, immediately enjoins us in conversation, pointing out the lay of the land, telling us about who the people were – they're known as Jornada Mogollon – and when they lived here and carved the inscriptions, roughly, he tells us in a nicotine gravel voice, around 600 to 1100 years ago.

This makes them more historical than ancient, but still Pre-Columbian in nature and derived from a long tradition of ancestral rock "art" in the Americas. The Jornada Mogollon lived in simple villages along flood plains of the three rivers in a then wetter environment, fed by life-sustaining snowmelt from glaciers atop the great White Peak.

"I'll tell you what," says the old fart, "no one really knows who these people were or where they came from, but I'd bet my retirement account it wasn't that spoon-fed Bering Strait theory. I know an old Indian who lives around here who told me their legends speak of coming from across the sea, a very long time ago. The proof is in the petroglyphs."

Here, the old fart gestures with a sweeping wave of his leathery hand. "See that knoll out there? Well, just behind it, you'll find pictures of boats. Feel free to wander off the path and see if you can find them."

My eyebrows raise. "Really!? Is that so?!"

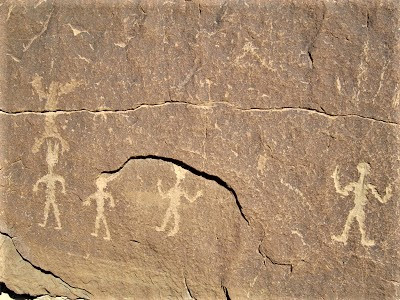

We set off on the trail and immediately come across dozens of the 21,000 zoomorphic, anthropomorphic and iconic petroglyphs – of faces, masks, insects, celestial symbols, human and humanoid figures, birds, animals, tracks, whimsical designs and geometric patterns.

We take our time admiring them, discussing their cryptic meaning, firing our imaginations, as we rise to a small crest where we're able to enjoy fabulous views of the Tularosa Basin and surrounding mountains. Off the trail, about two-hundred yards down, the knoll rises about 75 ft., where the old fart said we could find the depiction of a boat.

In all my days of seeking out petroglyphs, I've never seen one of a boat. The knoll is an outcrop of broken up, jagged chunks of rock, a gallery of etched inscriptions and symbols, waiting to be deciphered. Looking high and low, we finally locate the engraving – truly, that is what it is – a sailboat!

Tularosa – it just dawns on me – means red reed, and like peoples from similar lacustrine environments in Mesopotamia and Lake Titicaca, the Jornada Mogollon people certainly knew enough to harvest reeds and construct floating vessels out of them.

She’s sitting nonchalantly on a big rock like a queenly avian presiding over a vast dominion. After a second, it dawns on me that it's none other than one of them there famous roadrunners – that you never happen to ever see! And yet here she is, sitting and preening contentedly, largely unconcerned over the harmless bipeds.

Later on, at the visitor center, I report the sighting, and the old fart's wife chirps, "Oh, yeah, well guess what – that's our pet! She comes down every morning and we give her raw hamburger." I scowl and laugh at the slightly disturbing image. Nothing like a story of domestic corruption to spoil what I thought was a once-in-a-lifetime sighting!

Back on the main trail, several groups of people have arrived, but still, the place is so remote, it doesn't get an abundance of visitors. At least not on this blustery day. We continue the loop, encountering ever more bizarre and fascinating, complex and puzzling, petroglyph symbols.

These mystery people incised a Rosetta Stone's worth of undecipherable messages. What could be their possible meaning? Who were the "artists"? Although it is believed the Jornada Mogollon were responsible for the Three Rivers petroglyphs, generally no one knows for sure who was responsible for their existence.

Or what the meanings are of the varied symbols found throughout the Southwest, although it is inferred from oral histories and myth handed down over generations that they may represent hunting or fertility magic.

Of course, academia has proffered plenty of educated guesses as to their meaning. The BLM brochure, for example, gives insight into the prevalent circle and dot motif found at Three Rivers, relating it to Quetzalcoatl.

Certainly, trade with Mesoamerica occurred at this time. Copper and turquoise from New Mexico has been found in Mexico, as well as macaw feathers and seashells from Mexico found at archaeological sites in New Mexico. So, this connection seems reasonable to assume.

Other motifs hint at cosmological and genealogical stories and imputed magico-religious beliefs. Stepped frets represent (according to Hopi mythology), "sipapu" – the place where the Ancestral Puebloans emerged from the Earth.

.JPG)

Sipapu are features of all kivas, symbolic themselves of the opening to the sacred netherworld, prominent constructions at Ancestral Puebloan dwellings. Faunal representations are ascribed to animal clans, such as Eagle and Mountain Sheep, denoting separation and settlement.

Dancing upright figures, shield-bearers or wavers, are the Ancestral Puebloans, giving eternal thanks and praise to the spirits. At least that's my take. Ultimately, no one knows – not academics, perhaps not even modern day Pueblo Peoples.

Whatever their meaning and whoever brought them into existence for our future contemplation, is beyond knowing. All we can really do is enjoy them, revel in the titillating mysteries of unknowable antiquity.

It’s hard to imagine – or is it easy? – walking that dusty petroglyph trail, gazing out at the otherworldly desertified Tularosa Basin, that at one time, not too long ago, this was a land of huge lakes, abundant plants and animals, the lap of luxury in the bosom of nature.

Whoever they were, they were people who lived for untold generations in tune with the seasons, in harmony with Mother Earth. Or is this a mythical view of their existence? Wasn't it more brutish, more bellicose? Didn't they callously slaughter animals, wantonly waste resources, and foolishly contribute to their own demise, as Homo sapiens are wont to do?

Forensic archaeological evidence from more than thirty-three prehistoric sites in the Southwest indicate that something gruesome was going on. Cannibalism? Witch executions? If cannibalism, was it ritual?

Or, as some maverick investigators believe, was it intentional? – a desperate resort by a mineral deficient society to get iron and protein in their diet to sustain them as droughts, pestilence and raids plagued agricultural efforts.

Such a controversial view is a slap in the face to modern Pueblo Peoples, a hugely insulting inference. But whatever occurred, and why, the prevailing view among scholars is that, like academia's more realistic and repositioned understanding of the once thought of as "peaceful, agrarian" society of the ancient Maya, the cultures of prehistoric America were not always in harmonic convergence with one another.

David Wilcox, curator of the Museum of Northern Arizona, opines:

"We are in a period where everything Native American is (seen as) spiritual, sensitive and wonderful. We would like to believe that all of the nasty stuff was introduced by the Europeans, and before that it was all truth, beauty and love. Sorry, that's just not so. These were complex societies. We are all capable of doing those things."

All we know, or don't know, is that they were a nature-worshipping, pagan, animistic people, with high culture, art and technological sensibilities, who eventually fled in the face of climate change, drought, a fracturing of hierophantic leadership, and/or they were driven or forced out by the New World equivalent of Huns, Vandals and Barbarians at their kiva entrances.

Most of what they left behind – architectural ruins, remnants of roadways, causeways, irrigation canals, water containment features – are mute testament to a glorious past, but perhaps nothing speaks to their enigmatic existence more than the symbols they left on sandstone and tuff rock walls.

Intriguing, mysterious (?) symbols mythologizing their human saga. Canonizing the animals on which much of their well-being and diet depended. Glorifying spectral figures of divine origin to whom they prayed and worshipped, mostly for abundant rains to nourish their crops.

Today, we ponder and muse over them, in another time and space. We may know them only in our dreams and imaginations, as mysterious Ancient Ones who walked this Earth in beauty and harmony. And yet, the gnawing reality of ugliness and conflict confronts all who unveil the curtain of romance.

White Sands National Monument:

Dune-Swept Panorama Inspires Sands of Time Metaphors

Situated on the northern edge of the Chihuahuan Desert, the dunes were created over inconceivable millennia, as finely eroded gypsum, ground down to a glistening white sand like substance, got swept up, miles away from the fossil lake bed of its origins, into great wave like dunes engulfing 275 square miles of desert.

Normally, gypsum is dissolved by rain and snow, but because of unique hydrologic conditions present in the Tularosa Basin (no rivers drain it), the gypsum is trapped until winds blowing across the playa of alkali flats that is Lake Lucero carry the particles downwind.

Recognized as the largest gypsum dune field in the world, WSNM is a growing, pulsating, living, breathing ecosystem, constantly in flux, cresting, shifting, advancing inch by inch, sculpting a starkly beautiful landscape.

The flip side is that it is no place for humans, or for many animals or plants, for that matter, owing to the harsh, spare environment where only a few sparse plants and animals manage to survive, some with special color change adaptations, like the pocket mouse, some insects, and two species of lizards, including the bleached earless lizard.

The resourceful kit fox, coyotes, beetles, porcupines (who would guess?), and rabbits also make it their home. Even exotic oryx (African antelope), introduced by the State of New Mexico onto the White Sands Missile Range nearby, have adapted to the area, but the National Park Service considers them a threat to native plants and animals.

Fortunately, too, on this day, no testing of experimental weapons is going on – closures average twice weekly for a couple of hours. That's always been a paradox of the great iconic desert landscapes of California, Nevada and New Mexico:

Stunning natural beauty juxtaposed with / surrounded by top-secret nuclear and military installations, pristine skies crisscrossed with the contrail tailings from the overhead buzzing of hi-tech jet fighters, and the sense that amid the tranquility and beauty lies a dark, hidden side.

Summers at WSNM burn white hot, while winters can see temperatures plunge to freezing. This March day seems gentle and propitious – like, heck yeah, who couldn't live here, or at least hang out all day.

We wander around, veritably stupefied with awe, having caught the place on one of those incalculably precious days when storm clouds are amassing in one direction blurring sandy stretches with white horizon, and in the other direction a rendering of a fabulist's immaculate daydream of pillowy cumulus clouds drifting lazily across a deep cerulean sky.

The wind is blowing, but it takes stronger winds than today to lift up the grains owing to some principle of physics. It's enough just trying to grok the eons-long geological processes and forces that created the various types of dunes – parabolic, transverse, barchan, and dome – and the fragility of clinging life suitably adapted to find home and hearth amid the constantly shifting environment and such seeming desolation.

For us just-passing-through visitors, it is a speck in time moment, an ephemeral experience of being a part of something greater than a puny human lifetime.

Truth or Consequences:

An Overnight Stop in a Small Spa Town

Tiny buildings and an airstrip way off in the distance – spotted from a bend in the road – and the overhead buzz of another jet fighter is as close as we will ever come to seeing this place, even though a sign invites folks to drop on in and visit the museum and "trace the origin of America's missile and space activity, find out how the atomic age began and learn about the accomplishments of scientists like Dr. Wernher von Braun and Dr. Clyde Tombaugh."

No thanks, maybe next time. (I'm sure it is interesting.) We keep driving, swinging north to complete a near 300 mile loop in one day to end up in the town of Truth or Consequences. Surely you've heard of this town, once-named Hot Springs, right.

Back in 1950, in a gambit to bring attention to itself, T or C won a $50,000 (a ton of dough then) contest to change its name. Every year since then in May, Ralph Edwards broadcast his show, Truth or Consequences, from the town.

However, it was really a marketing branding boondoggle, in my estimation, because while it brought some fame owing to its unique name and association with Hollywood, its core competency – hot springs! – was forgotten or overshadowed for years.

Well, the city is trying to turn that around with new PR campaigns and upgrades to facilities. We intend to splurge tonight in a riverside spa and soak our tired, achy bones for the night. Turns out, because of "March Madness", all the nice places are booked, wouldn't you know it, so we end up having to sleep in a dive motel on the edge of town.

Although an up and coming town, T or C is still a bit down at the heels, but it sure seems that people love it here – and you can easily imagine the changes to come over the next ten years.

Artists and back-to-nature people and hippie-types flock here. Like the abstract portraiture artist Ruth whose whimsical Gambolin' Gal style paintings adorn the local breakfast joint. Like the hotel proprietor, an overly-affable bloke raising a nine-year-old daughter who crows to us that nowhere on earth could be a better, safer environment to raise a kid.

And the owners of the various spas gaining increasing popularity as word gets out about the underground bubbling hot mineral springs that surface along the downtown area and river's edge.

And then, in case you're unaware, there's Sir Richard Branson who chose the area around T or C as the place to build his Virgin Galactic Spaceport America facility – the launching pad for the world's first commercial flights to outer space sometime in 2011, believe it or not.

Virgin Galactic has already taken around $45 million in deposits for spaceflight reservations from over 330 people eager to look down, from beyond the Stratosphere, on our tiny blue orb, source of eons of geologic upheaval and millennia of human evolution, pageantry and historical drama, in order to experience, no doubt, without question, a seminal, indeed the single most transformative experience, of 330 people's lifetimes.

Soon, once prices drop, it will be just another thing that people do for fun and thrills.

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument:

Handprints of Time Mark Site of 13th Century Cultural Settlement

Our intended destination being another remarkable example of a preserved glimpse into the state's mysterious past – the Gila Cliff Dwellings.

Located in the northeastern heart of the Gila Wilderness, the Cliff Dwellings are reached from T or C via a drive on a narrow mountain road across the mountain divide – a “shortcut” to Silver City.

The scenic drive takes about three hours, owing to the winding road which pre-empts any attempts at reckless, impatient driving, and whose natural beauty offers up many pull-over spots to stop, get out, breathe in the fresh high altitude air of scented pine forests dusted with snow, and take a million pictures.

We finally zig and zag our way down to the other side, and turn off on the road pointing to the Cliff Dwellings, still another 40 miles away . . . on yet another winding, narrow steeply graded road where it's easy to be tempted with a heavy foot to get there quickly. I pull 'er in to a mom 'n pop gas station with an old-fashioned pump from the sixties and gas prices from a later century.

Inside the rickety store I inquire with the red-neck looking Anglo proprietor about the anti-Mexican gray wolf sign I notice posted outside. “Yeah,” he says, "damn big government" – he actually says "gubmint" – "and those crazy environmentalists forcing their ways on us rangers and farmers." I pay for the gas, allowing him license to ramble on about his special interest / anti-wolf stance.

Later, I learn that a few years ago, the Mexican gray wolf, once a native predator to the region, endangered since 1976, and listed as the most endangered mammal in all of North America, had been re-introduced to balance the ecology and keep the deer and elk populations down, but the ranchers and farmers have been all up in arms about it because, allegedly, a few of the (only) 50 lobos in the wild have eaten their livestock, killed their pets and endangered their children.

Really, now?

A few wolves roam in the Gila, but it would be rare to encounter one, let along a pack of the sociable animals, probably rarer than seeing a mountain lion. Still, it's wise to know what to do – and not do – should such an encounter occur. For the ranchers and farmers, specific prohibitions include hunting them or harassing them in any way unless caught in flagrante delicto doing what just comes naturally to them.

Once again, conflicts involving humans and displaced animals – well, let's just say the playing field is stacked – humans always win. May you live long and prosper, Grey Wolf.

Back on the road, no one riding our tail, with a reassuring tank full of gas, we enjoy a pleasant drive as the scenery gets prettier by the mile. We get to the Cliff Dwellings at around 10 am – it's a perfect temperature, blue sky kind of day.

With my old Block Island hat in tatters, I finally break down and buy a new one – with, yep, you guessed it, a road runner emblazoned on it. The volunteer lady (they're all retirees and/or college students on the bum for a semester) tells us to be sure not to take any food up to the dwellings, to keep little critters out.

What a crock of hokum, it turns out. No one else mentioned it – we see other volunteers and two rangers, and it's not written policy anywhere. But her warning anchored in my mind, I neglect to pack a lunch and we set off on our three hour outing without a single bit of food, which is utterly stupid, because afterwards, down on the West Fork of the Gila River, we're starving our butts off!

.jpg)

Not even a Clif (Dweller) Bar!

We do survive, just so you know, and once back at the car we grab some food and go sit down by the rushing river to picnic and watch the world pass by without a care, feeling ageless and full of youthful vigor. A line in a Borges verse comes to mind:

" . . . time is a river that carries me along, and I am the river . . ."

The easy mile loop starts off beneath a towering cliff face and winds pleasantly through a riparian gorge, rife with narrowleaf cottonwoods and willow trees, sustained by a constant flowing stream, bringing cheer and levity to the dark shady trail.

Cliff Dweller Creek originates from a small spring at the head of the canyon, flows into the Gila, and supports a cool and lush canyon environment of moisture-loving mosses, wild grape and flowers sprouting in grassy tufts along the creek.

So much variation in such a confined geographical area makes Cliff Dweller Creek, the high mesa, and its sheltered backside such a naturalist's dream, and provided the Cliff Dwellers with everything they needed to sustain an ample and rich existence.

We get to a lookout, and bask in – if you've never seen such a sight – jaw dropping views of the Cliff Dwellings, tucked high in several large alcoves in the orange cliff face.

Secluded above the canyon floor, removed from the turmoil and threat of invasive hordes, it is an incredible sight, a beautiful setting of abandoned residences and ceremonial rooms, constructed over 700 years ago, in a camouflaged setting where the Mogollon people could feel safe from marauders.

Who were these enemies, we wonder? One deviant researcher speculates that "Toltec thugs" made their way up from Central Mexico to dominate and employed cannibalism as a tool of terror to leverage power and wield control over a subdued population.

Other architectural and archaeological clues indicate these people were influenced by the Four Corner's "Anasazi" tribes who rose to high prominence, traded with them, and engaged in trans-continental commerce with people from ancient Mexico, as evidenced by the remains of a scarlet macaw excavated in Cave Three.

Many other ceremonial and utilitarian items point to trade among the peoples of a large region, including macaw feathers, seeds from Mesoamerica, a buffalo scapula, and textiles from exotic plants.

By the late 13th century, they were gone, here no more, scattered like milk pods to the four corners of the wind – abandoned were their sacred gardens of sustaining crops, the "three sisters" of corn, beans, and squash they planted along the river and atop the mesa; gone were their communal gatherings and spiritual congregations in the ceremonial rooms.

Vanquished, left to crumble in ruinous decay, for centuries – only the Chiricahua Apache remained as guardians and descendants. Geronimo said, “I was born at the headwaters of the Gila River” and the dwellings and other points of reference remain important to their oral traditions, history and cultural identity.

But ultimately, old Goyathlay, as he was known in the Apache dialect, was powerless to repel the new thugs and marauders – greedy, gold-seeking, land-grabbing Manifest Destiny driven Anglo settlers.

By 1884, in the first archaeological report by Adolph Bandelier, the invaders had severely damaged walls, broken and stolen pottery, removed artifacts, tools, and burned roofs in what was certainly driven by the antiquities trade, but no doubt also was a campaign against the idolatrous and heathenish.

In 1907, none too soon, Gila Cliff Dwellings became one of the first of 100 protected National Monuments. What a butte-iful and a-mesa-ing (not to mention gorgeous) place to put down roots.

May it forever be protected, and may its tantalizing mysteries and unanswered questions forever remind us of a vanquished past, a world we may never wholly understand, a world vastly removed from our own existence, but perhaps more alike than we'll ever know.

On the walk back, hungry as bears and eager to get down to picnic by the river of time that is me, we can't resist a quick detour on the Trail of the Past at Lower Scorpion Campground, where we visit a humdrum old structure – humdrum?

Wait a sec! Is there no magic in a crumbling storage bin or pit house 800 years old?

But still, c'mon, these are priceless!

Silver City:

A Brief Lay-Over in An Authentic Old West Town

Our diminutive room overlooks main street and has the look and feel of a French chambre. We're so tired from our exertions and excessive sun exposure, it's all we can do to just stroll the streets for an hour looking for an open shop or gallery – everything had closed by 4 pm.

So here we are, in Silver City, without much to do or see. Even the restaurants – all two of them on the main drag – aren't much to rave about, and they're way too expensive and not particularly inviting for the type of food we want – and they're crowded and loud – so we end up going to bed eating peanut butter sandwiches we throw together from our dwindling food supply.

Next morning, we wake up early, take our leave, grab tea and coffee and muffins at the cool Javelina coffee shop just below the hotel, check e-mail briefly (why?), consult the map and hiking book, and head out of town. Our next destination – another hot springs experience – San Francisco Hot Springs, located in a small canyon cut by the San Francisco River about 50 miles north of Silver City.

San Francisco River Canyon:

In Search of Elusive Hot Springs

.JPG)

No one – I mean no one – is around! We're getting used to being alone (and so spoiled!) in much of our wanderings in the remoter southern part of the state. Serenading birdsong fills the air, a few scrub jays escort us and a couple of deer lope off into the hills. It feels great to be alive, pumped full of vigor, health and youth! (Well, two out of three ain't bad.)

Soon we hear the rushing gurgle of the river – our first clue it's running high at this time of year – and make our descent along a rocky switch backing trail overlooking a stunning little valley filled with white-tipped water birch, willow, and oak, an unheralded desert oasis scene that qualifies as the prettiest spot on Earth at any given time – like right this second, for instance!

.JPG)

High rock wall formations colored vermilion and painted in splotchy desert varnish loom high, closing in the valley claustrophobically, but also lending an intimate setting to lovely natural surroundings. The springs lie about a thousand feet downstream from the trail, and off we go, looking for them, here, there, everywhere, amid piled up tangles of driftwood and snarls of debris deposited in heaps and mounds from a flash food.

.JPG)

We evidently pass right by any springs to be had and end up following a big bend in the river to a dead end. A fire ring lay unused for years, and the trilling song of a lovely canyon wren echoes in lovely heartrending notes.

.JPG)

Here the river squeezes through narrow walls, snaking off into some infinite world beyond never to be explored, affording us no further passage. We stop, listen, and stare off silently at the cathedral of natural beauty we find ourselves in – hot springs or no, this sight alone is worth the effort and detour.

Oh, well, no soaking in this little paradise, but what a wonderful diversion to a secret, special place where no human seems to tread except when there's soaking to be had, and then, I wonder, how many are curious enough to continue the trek downstream another half mile to the canyon's magical cul-de-sac?

Whitewater Creek:

A Stop-Over to Check Out a Slot Canyon / Riparian Paradise

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Catwalk spans high above Whitewater Creek, aptly named for its abundant gushing and swirling waters which originate high on the Mogollon Mountain peaks. When the heavy snow melts, raging white water comes crashing and thrashing and pounding through the narrow, twisty corridor, which has been cut through the easy to wear down volcanic rock.

.jpg)

More than 15 major floods have occurred over the last 40 years, to give some sense of reality to the dangers of getting caught in the back country gorges during a rainstorm or sudden melting caused by hot days.

.jpg)

The Catwalk is an amazing bridge like structure built right into the canyon walls, enabling anyone – even wheelchair bound hikers – to enjoy the rugged canyon that the erosive power of Whitewater Creek has carved out of the soft Cooney Tuff into one of New Mexico's few slot canyons. Unfortunately, due to a flood wiping out a portion of the Catwalk, it and the trail system beyond is closed to passage at the half-mile mark.

.jpg)

Shoot! No chance of getting caught in a back country flash flood today!

We're yearning to continue the footpath to explore ever more scenic beauty in the inner depths of the gorge, but we have no choice but to turn around and retrace our path.

.jpg)

We walk slowly back, admiring the brown and gray desert hills contrasting with the lush oasis environment of riparian green, a garden of cottonwoods and Arizona sycamore trees, reminding us very much of a near and dear Bay Area location – Sunol Regional Wilderness and sycamore / bluff-lined Alameda Creek, believe it or not.

.JPG)

The diversity of plant and animal life found at Whitewater Creek ensures an unusually rich ecosystem supporting American dippers, bighorn sheep, rattlesnakes, and many other symbiotic animal / insect / plant relationships. The roving bands of Chiricahua Apache knew this land inside out, and their knowledge of hidden springs, hide-outs, and edible and medicinal plants, helped them remain unconquerable for years.

.jpg)

POW! WOW! This place was where they called home, or at least their back yard!

Mogollon:

A Brief Detour to Check Out a Ghost of a Town

Endeavoring mightily to squeeze every historic attraction and natural scenic wonder into our fleeting itinerary, we drive 9 miles up and up, ascending over 2000 ft., through the Mogollon Mountains, along a curving, narrow road, going seemingly nowhere, but headed for the old mining town – now a ghost town – of Mogollon.

.JPG)

Established in the 1890s, in aptly named Silver Creek Canyon, the camp, because of its remote location, was one of the Wild West's most shoot-'em-up towns, with miners also dying by the cartload of consumption and accidental death. Devastating fires and floods also plagued the residents, but they were resilient and determined to keep rebuilding. Such was the powerful allure of gold, the irresistible magnet of silver.

By 1915, the population peaked at 1500, and the town sported all the attractions and conveniences expected of a bustling, "civilized" community – a web site devoted to the town's history describes:

.JPG)

" . . . the electricity, water, and telephone facilities. The school offered education to about 300 children, and boasted four merchandise stores, five saloons, and two restaurants . . . the town had extras including a hospital with three physicians; a photographer; an auto Line; the Midway Theatre; an ice maker; a bakery; and two red-light districts, 'Little Italy', the home of eighteen white girls at the west end of town and the Spanish section on the east."

.JPG)

By 1930, most of the mines had shut down, unable to compete against the crash in ore prices, and only a couple hundred people stuck it out. Today, a few hardy souls, about 15 of them, remain – doing what, it's not certain. Ultimately, millions of dollars worth of gold ore and silver bullion were shipped by mule train to Silver City.

Driving through main street – it's now too chilly to get out and walk – we pass a few decrepit relics and old buildings, snap a picture of two, read a placard or three, inspect a restored cabin. I notice a guy fixing some mechanical contrivance in his yard, and he looks up and eyes us somewhat suspiciously, I feel.

Well, point of fact, the town and its main attractions – a museum and the Silver Creek Inn saloon built in 1885 – are closed until summer. Bodie, it is not quite, even though it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1987; even so, what little time we devote to exploring the main drag, it's difficult to believe, since I count only a dozen, that over 100 historical buildings remain.

What part of Mogollon did we miss, I wonder. We do see – and learn later – that the old weather-beaten General Store, which looks authentic as hell, is actually a prop from a 1973 Western flick called My Name is Nobody, starring Henry Fonda.

.JPG)

Mineral Canyon:

A Magical Place Emanating Spiritual Power

Created from incessant erosion, the rock walls, pinnacles and hoodoos in the canyon are colorfully stained from mosses, lichens and mineral leeching. Situated on the western boundary of the Gila Wilderness, snowmelt-fed Mineral Creek has carved one of the most beautiful canyons in New Mexico.

Make that anywhere!

Over millennia of erosive action, cutting ever-deeper through layers of volcanic sediment to leave isolated pillars and craggy peaks and sheer walls rising 1000 to 1500 ft. high.

All with a beautiful stream running through it, gurgling its incessant song of water. We reach the trail by driving down an unmaintained gravel road for six miles. No one, absolutely no one, is here – it feels like it could be 100 or 1000 years ago, seriously. We pack a lunch, and set off on a trail that soon takes us right down to our first creek crossing.

At first I try to step on logs and branches, in an effort to keep my feet dry, but how silly. I fall in trying to negotiate a slippery log, and finally just give in to the easier method of wading in the water in my hiking boots. Gambolin' Gal's in her Tevas, but the water is cold and numbs her poor little feet so she eventually trades them in and walks in her hiking boots as well.

Much better. Now, the going is easy, and quite fun and adventurous, as we splash along gleefully in the creek, following its snaky contours, eager to discover new sights around each bend. Mineral Canyon immediately and unrelentingly charms, enchants and amazes, with every turn and bend in the gushing, swirling, cascading creek.

Sunlight filters down and bounces off walls, reflecting off rippling water surfaces to create heaven glow scenes of beauty and reverence. We stop to ponder our whereabouts, our place in this intimate world of natural wonder.

The desert landscape high above is a constant source of soothing visions – various sculptural formations painted in reds, oranges, yellows, salmons, and lavenders, heightening or muting colors as the sun's passage cast shadows or bakes the rocks in vivid rays of goddess beams.

We come to a special place where the creek tumbles over a five-foot rock shelf and then scurries in rippling momentum down a broad swathe of cascades over rust-orange bedrock. Willows and odd gnarly cottonwoods sprout where they can affix roots. We sit here in this sacred place of power, not saying much, just absorbing its spirit.

We eat, wander about in desultory exploration, probably pass three or four solid hours here, doing nothing, really, except being part of it, in whatever way we're able to incorporate or insinuate ourselves, our brief, ephemeral selves, into this timeless tableau.

Finally, realizing the sun has slipped behind the loftiest of the high walls, we reluctantly – and oh so slowly, not wanting to relinquish it – make our way back. I do not want to leave this special place. It's impossible to pull myself away.

I start to leave, then stop, turn back to get a final eyeful and soul helping of the place. Doubtless, the Apache hid out here, too, made it their encampment. For us, we are mere specks in transition. For the old ones, though, this was their home, their hearth and heart. This is where they lived, celebrated, died.

How sad, they were rooted out from this existence, forcibly corralled, their spirit vanquished and crushed. (They're getting a little bit of "payback" today with their casino riches.)

He and his men – crude, rude, rough and thick skulled philistines – defiled the land in the beautiful gorge, killed all the game, and polluted the stream.

Laughingly, deliriously drunken with their mineral riches. It's no wonder that the Apache – guerrilla warriors desperately eking out a marginal subsistence on the fringes of the White Man's incursions and lust – under the leadership of Chief Victorio in 1880, dressed Cooney in an arrow shirt on his way back from getting supplies.

We pay homage to the history and landmark, but feel little respect or sympathy for Cooney and his ilk who contributed to the misery and demise of once-free and proud people who roamed these lands for thousands of years. But maybe like wolves, just doing what comes "naturally", Cooney and his ilk didn't know better.

Naw, no way! That's just letting these bastards off the hook.

Interlude:

Busted Flat in the Middle of Somewhere

.jpg)

My timing is terrible – a county sheriff's coming the other way and instantly his lights come on. At first, I can't imagine it's on account of my (unintentional) scofflaw driving, but seeing no other vehicle in sight, and his U-turn a few seconds later, I realize he's pulling me over, the cop-sucker.

In my rearview mirror, I see him trundling over, hand subtly angled toward his holster, just in case. He's Native American, short, and wearing sunglasses.

"Can I see your license, please."

"Yes, sir."

"Do you know how fast you were going?"

"Uh, no sir."

"67 miles per hour. Do you know the speed limit? It's 55 miles per hour. There's a sign back there at the top of the hill."

I confess to not having seen a sign, and lamely shook my head.

"My bad, officer, I guess I must have missed it."

"Is this your car?"

"No, sir, it’s a rental." (Utmost cop-sequious voice.)

"Where are you coming from?"

"Albuquerque, sir."

"Where are you going?" (Is this a zen interrogation?)

"Chaco Canyon, sir."

"Wait a moment, please."

"Yes, sir, thank you, sir! You're a good man," I say to the cop, who I think is pleased to hear that coming from a white boy stranger from California. (It definitely pays to be obsequious!)

Jubilantly, I tear off in a squeal of burning rubber and dust – not! We drive on, witnessing a flaming sunset, now in gloaming darkness, past El Malpais National Monument – a badland (make that wonderland) of lava flows, cinder cones, tube systems and high ridges and mesas inhabited by contemporary groups of Pueblo Peoples of Acoma, Laguna and Zuni.

We'd love to stop, check things out – but I keep pushing it until we get to the nondescript town of Grants, a self-proclaimed safe and happy community of 9000 people from many cultures and backgrounds, offering "low property taxes, inexpensive housing, the convenience of a nearby large city, and an abundance of open space."

And hopefully, a nice, cheap hotel. By now, it's around 10 pm and we're toast. We argue about which nice, cheap hotel we're gonna crash in. Honey, they're all the same! No, they're not! Yes, they are! No, they're not! We end up settling on – what is it, a Motel Sick or Discomfort Inn? – that stinks like all cheap hotels do of yucky cleansing and perfume agents. (Where is our camping gear when we need it?)

We reflect briefly on the day, check maps and guidebook, and fall into a dreamy stupor watching a Larry King Live special on repeat offender child molesters. Huh? Click.

.jpg)

Chaco Canyon:

Mystery and Prehistory, Ancient Culture Flourishes in Desert Wilderness Setting

.JPG)

.jpg)

The aboriginal homeland of the "Chaco People", the Ancient Ones, the Ancestral Pueblo (anything but Anasazi, considered a derogatory term meaning "Enemy Ones"), who chose these canyonlands, mesas and desert washes as the place to set down cultural roots and flourish.

.JPG)

Flourish they did, here in a seemingly unlikely setting for 300 years, beginning around 850 A.D., forging a center of civilization whose influence and power spread out over a great arc in the San Juan Basin.

.JPG)

In turn, we know inferentially that the builders of Chaco's structures were influenced by other Four Corners cultural traditions. The pervasive Toltec culture of Central Mexico, for example, can be seen in various stylizations and clues. The Toltec built Teotihuacan and extended their influence and dominion to Yucatecan Maya civilization at Chichen Itza.

.JPG)

And far beyond Mesoamerica, they forged into what is today the U.S. Southwest and probably stretched their tentacles of influence as far as the U.S. Midwest (check out Cahokia outside of St. Louis).

.JPG)

Probably the basis for all this long-distance contact – indeed the linchpin of a prosperous society – involved expansive trade networks. Traffic in turquoise, for one, helped Chaco develop into a ritual and ceremonial center.

.jpg)

The complexity of social life, as evidenced by impressive architectural achievements (over 400 settlements), trade with littoral peoples from afar, a 400- mile network of roadways, all give clues to Chaco’s clout and status as economic, ceremonial and administrative powerhouse of the prehistoric American Southwest.

For three centuries, generation upon generation, Ancestral Pueblo, in the service of the Scarlet Macaw Sun God, erected multiple-story stone buildings with timber construction using over 200,000 trees from mesa top forests 75 miles away. Imagine the organized workforce effort, the control required of a corvée labor force to pull this massive public works project off.

.JPG)

With precision planning and unique construction techniques and masonry styles that evolved over time, the first of the Great Houses went up in stages.

.jpg)

Pueblo Bonito, Una Vida, and Penasco Blanco, followed a 150 to 200 years later by Chetro Ketl, Hungo Pavi, Pueblo Alto, Pueblo del Arroyo, Kin Kletso, Casa Rinconada, and the others, Tsin Kletsin, Wijiji, and Kin Bineola, and probably dozens of other small structures crumbled to dust and lost to time.

.JPG)

Traditional Navajo lore (they are not considered Ancestral Puebloan, but nonetheless they trace their roots to Chaco) has it that Chaco Canyon is known as the place of the Great Gambler, a mysterious figure from unknown parts south – Toltec invaders from Mexico? – who enslaved the Pueblo peoples and forced them to build the great buildings. Eventually, this trickster despot was "outwitted and driven away."

.jpg)

Now, here’s a harebrained idea: the great D-shaped centers of Chaco Culture were nothing more, nothing less than . . . the original Indian Casinos! Mystery solved! (Who, in this scheme, were the pit-house bosses, I wonder.)

.jpg)

Another brainiac viewpoint, espoused by maverick researcher and world-renowned explorer and adventurer Richard D. Fisher, proclaims on his website that the kivas and Great Houses are nothing more, nothing less than grain (corn) silos.

.JPG)

Basing his hypothesis on logical associations from large-scale granaries at ancient sites such as Paquime Sky Island in Mexico, Fisher dishes up unimpeachable logic in deconstructing widely-accepted scholarly doctrine. He writes:

.jpg)

“They built distinctively large impressive buildings whose primary purpose was for the long term storage of vast quantities of corn. They had platform mounds for religious ceremonies. They had very distinctive agricultural strategies which allowed for increased population densities and surplus energy for labor.

.jpg)

"They built large numbers of round rooms for grain storage and food preparation. They utilized ingenious techniques to produce fertilizer. I suggest that with their surplus corn growing capacity, they developed large religious ceremonies atop the platform mounds in which tesquino/corn beer was consumed as a stimulant.

.jpg)

"These ceremonies attracted the clans from across the Chaco great house system . . . What I am striving to explain is how a fundamentally practical system of managing the food supply in Chaco Canyon and elsewhere translates into a sacred life-style and cultural legacy that endures to this day.”

.JPG)

Do you buy it? Well, there is always a simple answer for every complex question, and it is always wrong, as H.L. Mencken was fond of reminding smug academics and maverick thinkers alike.

.JPG)

I ached with a yearning adolescent fury to understand what happened, where did they go, how could a great civilization and its entire people vanish, just like that, overnight? I couldn’t get my little 11-year-old brain around the concept.

.jpg)

Turns out, as a student of archaeology years later, Great Demises are a common theme that tie all ancient great cultures together in a fate of ultimate disintegration.

By 1132, the last of the construction took place, and gradually (not quite overnight), Chaco became abandoned, a precursor ghost town, as the people scattered, fled in response to centralized authority dissolving in the crisis of some natural calamity or wide-scale fracturing of the social fabric.

.JPG)

Where did so many people go? Similar to the mysterious disappearance of the ancient Maya a few centuries prior, Ancestral Puebloans probably fled to outlying parts in a mass diaspora, assimilated with other tribes, and began to reorder their lives in accordance with the timeless cycles of migratory transhumance, of simple existence, free of unifying cultural influences.

.JPG)

Their descendants live on today, a culturally vibrant, noble people, in possession of many legends, myths and shared collective remembrances of the ancient days, the old ways . . . and yet so much more is lost to the ravaging oblivion of time that we will never, ever truly know what happened.

.jpg)

We spend most of the day exploring Chaco's key dwellings, reading the literature, engaging our minds in fanciful reconstructions and imaginings of how things must have looked, and pondering the stark beauty of their desert homeland.

.JPG)

With the day warming up after making the rounds at Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl, we pack a lunch, ensure our water provisions, and – under a blazing sun mercilessly bearing down in a bright blue sky – we set off on Petroglyph Trail on a four mile round trip hike.

.JPG)

.JPG)

We're hoping to have the energy to continue our sunbaked trudge along the sandy basin floor to an alluring destination at trail’s end where a painted sunburst adorns a rock, probably representative of the supernova explosion in 1054.

.jpg)

Photo courtesy of Alex Marentes ("Buggs" on Flickr)

Quite intriguing. But after a small lunch break in a tiny nook of shade provided by a boulder, with the sun beating down relentlessly, and I in shirt-sleeves and no sunscreen, besides my bum ankle, and Gambolin’ Gal not up for it either, we wisely conclude it would be hubris of the highest order to add the extra mileage and exposure.

Besides, we’re short on – the thing Chaco Canyon has always been short on – water. We turn back and call it a day in the back country, a hair disappointed not to have laid eyes on the famous pictograph memorialized on a protected rock face by an ancient astronomer / artist.

.JPG)

We check out Casa Rinconada next. Built in a style more typical of a village community than the grand public ceremonial buildings of Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl, the "Casa" is a short walk from the parking area to the site of the largest kiva found at Chaco, and one of the grandest in all the Southwest.

The subterranean sacred circle measures 8 to 10 feet deep with an inside diameter of 60 feet, complete with ventilation shafts, smoke pits, reliquary niches, and seating benches to hold up to 100 people.

As hard as we might try to imagine a spectral people intimately engaged in sacred ceremony, in some ritual invocation to the Corn Goddess, the Rain God, Father Sun, Mother Earth, I can't help but ponder Fisher’s heretical theory – bolstered by 16 points of (irrefutable?) contention – see Canyons Worldwide – that kivas could not have been, would not have been, and frankly were not religious structures with specific ceremonial uses.

They were, rather, he adamantly contends, “corn silos, as might be expected to be found in a culture whose entire purpose and focus was on growing corn.” Do you buy it? Too corny of a theory? Whether church or grain silo, some kind of high sacrament was associated with a culture whose entire lifeway was – like ancient Mexican civilization – centered on corn.

Walking around this gigantic kiva, we come to a window frame, through which a shaft of light shines through on the morning of the Summer Solstice. The Ancestral Puebloans, like most high cultures of ancient times, were keen observers of the night sky and understood celestial relationships to earth and incorporated complex alignments and geometries into their sacred construction techniques.

.JPG)

They oriented their kivas and Great Houses to solar, lunar, planetary and cardinal directions with Egyptian-like geodetic precision, and went to great engineering and intellectual lengths to align sophisticated astronomical markers and other communication features.

Gazing beyond to the mesas, with the ceremonial centers appearing in the distance as Lilliputian ruins, a grander vista opens, an azure desert sky stretching far and wide, dappled with fluffy clouds spreading to infinity's low horizon.

.jpg)

Sitting quietly, no one about, alone in a contemplative state, we stare out at the somehow forlorn emptiness of the desert, at the same time filled with a connective sense, a soul-belonging sensation, picking up on a psychic thread to some long-vanquished energy.

Contemporary Pueblo Peoples believe that this energy is not vanquished, but omnipresent, vibrant, part and parcel of their religious heritage and cosmological belief system.

.jpg)

Now, I'll buy that!

.jpg)

Time to pull ourselves away from the fascinating magnet of Chaco Culture. Last time – a dozen years ago – we camped here, and wish we could reprise that special experience, but it's not meant to be.

.jpg)

We stop in the Visitor Center to browse, and engage in chit-chat with a Puebloan woman ranger. Her thick horse-tail black hair is braided and drapes nearly to the ground. Skimming a book, I find a petroglyph photo that I had not seen at Chaco, and she informs me they're nearby, but, sorry, off-limits to the public. They’re by far the most decorative and expressive of all the carved symbols at Chaco.

.JPG)

Oh, well, we've seen a lot, but can't expect to see everything. On our way out, we pull to the side of the road to admire a stand-out geologic feature, the 400 ft. tall Fajada Butte, rising to over 6600 ft. above the desert floor. The sentinel is a spiritual monument, a sacred island in the sky.

.jpg)

The Ancient Ones constructed sophisticated solstice and equinox markers atop. Now off-limits, like the petroglyph panel in the book, we can only appreciate it from afar and imagine the elaborate precision that builders and astronomers took to create this complex and sophisticated calendrical system.

.jpg)

.JPG)

As the declination of the sun increases or decreases during its passage across the sky over the course of the year, depending, two sunlight daggers either frame the spirals (Winter Solstice) or one dagger slices directly through its center point (Summer Solstice).

.JPG)

Why would Ancestral Puebloans record so precisely the cycles of the sun and moon? For one, it demonstrated keen and unique hierophant and spiritual technician abilities to understand, control and manipulate in God-like fashion extraterrestrial lunar cycles and solar rhythms.

.JPG)

Naturally, this rendered a superstitious populous awestruck and left them in complete and utter adulation and amazement at such magical feats of knowledge, such as to synchronous planting and harvesting timings with the orientations of phenomenological events and astronomical observations. All priestly power, the world over, in ancient (and modern) times, hinged on their ability to bamboozle the masses and convince them of their entheogenic ("the divine within") power.

.JPG)

Driving out of Chaco Canyon, we leave behind the mystery of the Great Houses, the kivas, the many dwellings and agricultural features – evidence of dams, irrigation canals and water catchments hint at water scarcity and preciousness – on which one of the Southwest’s most sophisticated cultural centers was built and sustained.

It's difficult relating to our present circumstances, driving away in a big SUV, our reliance on an oil-based, carbon-burning economy, caught up in a modern world of overpopulation, crime, war, strife, poverty, hunger . . . and yet, how much have things changed, I wonder.

.JPG)

Humans have always been prone to war, subject to famine, prey to erosion, deforestation, salinity, soil infertility, and general resource depletion – all of which have been proposed as causes for the abandonment of Chaco's great centers of culture.

.JPG)

Who knows, one day, perhaps, future archaeologists, maybe from another planet, will dig through the detritus of our own sorry-ass civilization and come up as empty or wrong-headed in their interpretation of what we were all about as the Venusian scientists in Arthur C. Clarke's short story, "History Lesson", who dig up a small metal box and based their entire reconstruction of the extinct inhabitants of Earth on this one treasure-trove discovery.

.jpg)

Clarke's kick-in-the-pants ending drives home the point of all our Mickey Mouse understanding of reality, of what we know and do not know:

.JPG)

"But all this labour, all this research, would be utterly in vain . . . millions of times in the ages to com . . . those last few words would flash across the screen, and none could ever guess their meaning: A Walt Disney Production."

Bodhi Manda Zen Center:

A Respite from the World Too Much With Us

The drive out of the canyon towards Santa Fe – where we think we’ll end up by evening – takes us up to a higher elevation zone; snow still covers the ground, and pine tree forests reign. I catch a far-off glimpse of a lone coyote stalking across a barren stretch of snow-covered plains, and pull over to take a picture. The coyote turns and looks back over his shoulder, then saunters off indifferently.

What a different world up here at 7500 ft. – but one which the Ancestral Puebloans and their brethren knew well, for it is the world where they hunted game, felled trees, and escaped the brutal desert heat during the summer months.

It’s a longer drive than anticipated, so I turn south and head back into the Jemez Valley where we had been a few days before. Deja vu deja vu. How strange to be back here, after completing a thousand mile loop in just four days. Somehow, then, I knew we’d be back to experience the luscious hot springs at the Zen Center, and sure enough, that's where we're going.

With that famous New Mexico light shining on red rock canyon walls that Georgia O’Keeffe rhapsodized about – "All the earth colours of the painter's palette are out there in the many miles of badlands . . ." – and the Jemez River winding its sweet way through dense thickets of brush and forest, and yogic devotional chanter Krishna Das' spiritual intonations emanating from the NPR radio station, we pull into the Bodhi Mandha Zen Center of Rinzai-ji just as Krishna Das winds up his chant – perfect, felicitous timing.

The chief resident priest, or Vice-Abbess, Jiun Hosen – immediately comes out to greet us. She is about 50, donned in spiritual looking vestments, and her head is shaved bald with a copper green patina coloring her shiny pate. Her gentle eyes glow with a radiant calm, her demeanor at ease and airy.

She bows, hands pressed together namaste-style, and asks how she may be of assistance to us weary and obviously wayward straggler-travelers. We wonder if she recognizes us from when we were here with Pia and the kids and she had come out to greet us in exact same fashion. Not knowing the center was closed to the public – we missed the entrance sign that proclaims, “Closed to the Public” – we inquire about lodging for the night.

She says, why yes, we’re in luck, pure serendipity, even though a scholarly conference on religion and spirituality is taking place, with professors and experts from around the world in attendance, but it is meant to be. There's an extra dorm room if we want it, for 50 bucks each.

At first we balk, thinking, geez, a 100 smackers. She escorts us to an inviting room in an old wooden dorm building – it is charming and warm – and leaves us to consider. Let’s put this in perspective – what's a 100 bucks for a beautiful experience, and all the hot soaking we can get for the night and the morning?

Compare this to our experience in T or C, where we shelled out sixty bucks for a dumpy room, and another thirty for just one hour in a private outdoor tub. It’s – I’ve come to hate the expression – a no-brainer.

Hosen has been a resident of the monastery for 30 years, we learn in an evening soak together (clothing mandatory). Her teacher, Zen Master Joshu Roshi, turns 103 on April 1, and has devoted the last 48 years of his life to teaching the dharma with boundless compassion, grace and patience.

I tell her that my twin sisters share the same birthday. She seems delighted. Our interaction is effortless and comfortable, like we're old soul-friends. We ask her some questions about why she chose the monastic life. It's a common tale of wandering, searching, questioning, finding.

She had been a lost and confused young woman, traveling the country, when she came upon an event hosted by the Zen Master. She was drawn by the Buddhist philosophy of learning "to live the experience of mutually dissolving our self-centeredness, allowing for a new self to manifest itself in a new moment's time."

Established in the early 70's, with the help of one of his students, Michelle Martin, Roshi said, "You find hot springs, I come." The Jemez Valley is such a beautiful place, radiant with spiritual vibes, that the Roshi said he would have come to live and teach here even if the added attraction of hot, healing mineral springs weren’t part of what makes the area so special. And this coming from a Japanese “onsen” (hot spring) lover.

We ask her if she misses anything about the secular world. Not much, she says, having found ultimate peace, free from greed, desire, fear of death, and – this surprises me – all her questions have been answered about the metaphysical nature of our life and existence. “There are no more mysteries,” she tells us in a calm matter of fact voice.

She is gentle, serene, sweet, and loving, wanting nothing, trusting in everything. It is enough, she tells us, to live simply, pray simply, "through sewing, peeling garlic, digging ditches, weeding, feeding the birds, planting, chopping, washing dishes, washing windows, raking gravel, folding clothes" and a myriad of other activities.

It seems we become instant and fast friends in that moment, enjoying one another, laughing and crying, breaking down the barriers of ourselves. Probably all just a pleasant illusion, a deep, spiritual, possibly karmic, but passing, soul-connection.

This is called living Buddhism.

After our soak, and good night to Hosen, who invites us to sit for Zazen meditation and join them for a breakfast of oatmeal the next morning, we walk up the street for a bite to eat at Los Ojos Bar & Package – a rustic joint that doubles as a museum, with antique artifacts and old historic photos, and serving up cold beer and tasty vegetarian delights.

Some of the scholars, along with an assortment of oddball characters, cowboys, and regular old folks are packed in the front room, watching on the big screen teevee New Mexico State punish Montana in the first rounds of the March Madness college basketball tournament. Another group of six people are engaged in a rowdy game of poker. Lots of whoopin' and cheerin' and drunken revelry – quite a contrast from our peaceful zen digs.

The next morning, after another wonderful soak in solitude at sunrise, with whirls of steam rising up out of the mineral pools lending the scene a Ridley Scott cinematic effect, Hosen proudly offers to show us the new Zendo meditation / prayer hall, eight years in the building.

.jpg)

It is truly a beautiful room, fusing ancient traditions of Japanese Zen Buddhist architecture with modern New Mexico elements. The hall is made of rammed earth materials, Pau Lope hardwood, tin roofing and tatami mat floors. It is, to be expected, replete with all the musical and liturgical accoutrements befitting a world-renowned Tathagata Zen Center.

Hosen tells us it's entirely geo-hydro heated and takes me to the back of the room, opens a closet door, and points to the Rube Goldberg-like newfangled piping and gadgetry that makes the ecologically friendly energy system work. As we're leaving, the conversation inexplicably turns toward getting old, suffering, dying, and how she recently cared for her mother and was there for her passage from this life.

We mention being there for our beloved, dying dog, Osa, which might seem callous until you remember that dogs are considered Buddha nature incarnate. Hosen nods affirmatively, in tune with her faith of compassion for all living beings.

Finally, with namastes and sincere expressions of thanks and gratitude, and "we'll be back" and "see you later", we take our heartfelt leave. Please come back soon, Hosen tells us. I will always be here, unless, she sighs, she's in the LA area taking care of the Roshi.

I ask Hosen why he doesn't return here, to his beautiful, peaceful retreat, to live out his final days. She nods, shrugs, and says if that is his wish and desire.

Bandolier National Monument:

Time-Tripping in Frijoles Canyon

What other inexhaustible wonders can possibly await us? How about Bandolier National Monument, next up on our itinerary through geologic and cultural time.

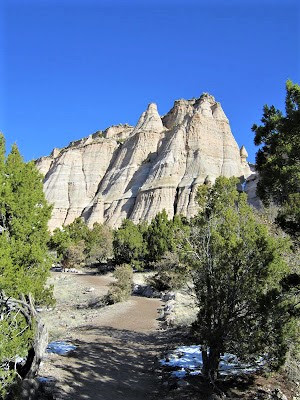

Located in canyon / mesa country of the Pajarito Plateau – formed by a million-year old volcanic blast that covered the land with a thousand feet of ashy debris – people have been coming to this area for 10,000 years or more like they have been coming to all canyons that beckon to the human spirit.

For millennia, various people migrated in and out of Frijoles Canyon, depending on seasonal variation of game, water sources, weather, and other factors. And they learned increasingly sophisticated agricultural techniques of agriculture.

As they learned to plant, harvest and store surpluses of corn, and other main staples they were able to grow (beans and squash), they gradually settled into a sedentary way of life, living peacefully in and around Frijoles Canyon, beneath the towering volcanic tuff walls soaring 1000 ft. above, pockmarked with holes like Swiss cheese, some big enough to erect dwellings in.